Small boats bill: What is the government planning and will it work?

The government has unveiled new laws that ministers claim will tackle small boat crossings in the English Channel, but questions are mounting over how the proposals will work.

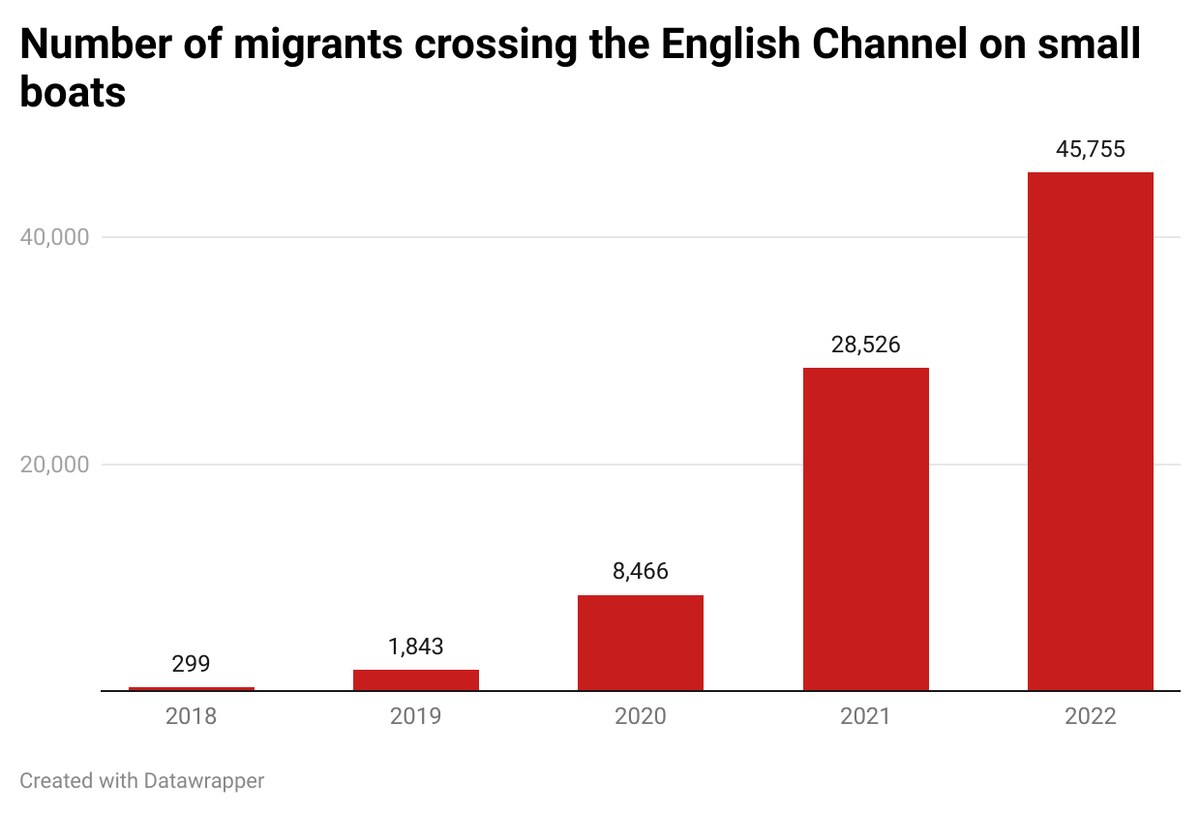

Rishi Sunak has made “stopping the boats” one of his five priorities and has come under mounting pressure from Conservative MPs to take actions as numbers continue to soar.

Senior Tories have told The Independent they fear the prime minister is “over-promising”, and that the legislation cannot be brought into effect before the next general election.

One former minister predicted that the bill will face strong opposition and could be mired in new legal challenges, as the Rwanda scheme remains stalled.

Meanwhile, the Home Office internally estimates another rise in small boat crossings in 2023, following successive annual records as previous attempted “deterrents” failed.

More than 3,000 people have crossed the Channel so far this year - double the 1,500 seen by the same point in 2022, which was itself a record year.

What is the government planning?

Suella Braverman told parliament it would place a legal duty on the home secretary to remove anyone who arrives on a small boat, either to Rwanda or another “safe third country”.

“They will not stop coming here until the world knows, if you enter Britain illegally, you will be detained and swiftly removed,” the home secretary said.

“Removed back to your home country if it’s safe, or to a safe third country like Rwanda. That is precisely what this bill will do. That is how we will stop the boats.”

The bill lists four conditions that people must meet to be subject to the new legal duty. They must have entered “without leave”, for example by small boat, arrived after 7 March 2023, without coming directly from a country where their “life and liberty were threatened by reason of their race, and without having leave to remain in the UK.

The text of the bill states that the duty is to remove eligible people “as soon as is reasonably practicable” after their arrival, without explaining what that means, or what happens if removal is not “practicable”.

There are no operational returns agreements in place with EU countries and the Rwanda programme has stalled, meaning that is not currently “practicable” to deport most asylum seekers to safe third countries they have passed through on their way to Britain.

It is a violation of international law to send refugees back to the country they fled, or others where they could face mistreatment.

The bill also states that people will be detained ahead of removal, and then ban them from re-entering the UK or obtaining British citizenship in future.

How can asylum seekers be made “inadmissible”?

Inadmissibility is a legal concept drawn up by the government to target people who it argues could have claimed asylum elsewhere, but attempts to use it against small boat migrants have so far floundered.

Since the UK’s current inadmissibility rules came into force with the end of the Brexit transition period on 1 January 2021, more than 20,000 asylum seekers were “considered” for inadmissibility and 18,500 were issued with legal “notices of intent”.

But only 83 people were served with formal decisions that they were inadmissible for asylum in the UK and even fewer - 21 - were forcibly removed. Almost 10,000 of the people originally considered under the scheme were then accepted into Britain’s asylum system.

A document published last year on what constitutes “inadmissibility” says it includes people deemed to have a connection to a safe country that is not the UK or their home nation.

That means that they have been recognised as a refugee in, travelled through, made an asylum application to, could have made an application to or has a connection to that country “on the balance of probabilities”.

Guidance for Home Office staff gives examples, saying that an asylum seeker who “passed through Belgium” before getting a dinghy to the UK could be declared inadmissible.

“An admission from the claimant that they had spent a couple of weeks in Brussels staying with friends whilst trying to find an agent to bring them illegally to the UK would likely constitute evidence that they had been in that particular country,” it states.

“The decision would also need to consider whether the claimant has provided any exceptional circumstances as to what they could not have made an application for protection in that particular country.”

The document states that even if asylum seekers deny having stayed in a safe country previously, “material in their belongings such as receipts and tickets from Belgian shops, services and transport showing time and freedom of movement in Belgium would likely meet the standard of proof required”.

What “safe third countries” can people be sent to?

A Home Office document says its rules “provide the grounds for treating an asylum claim as inadmissible to the UK asylum system, if a person has earlier presence in, or connection to, a safe third country. It also provides for the person to be removed to that or another safe third country, with that country’s permission”.

But there are a very small number of countries who currently give such permission.

Before Brexit, the UK was part of an EU-wide regulation that allowed the transfer of asylum seekers to countries they had previously stayed in on their way to the UK.

It allowed Britain to send people to France, Belgium and other countries deemed responsible for them because of their previous presence, while EU nations could safely transfer refugees to Britain if they had family or other connections there.

But the deal has not been replaced by the EU and individual nations have told The Independent they will not negotiate the bilateral “returns agreements” promised by the government during Brexit.

The gap caused ministers to pursue the agreement struck with Rwanda in early 2022, which effectively tried to designate the African state a “safe third country” for similar processes previously used within the EU.

Current government guidance states that removal to Rwanda should be considered if it “stands a greater chance” than removal to France, Belgium or other countries asylum seekers are deemed to have a connection to because of their mode of travel to the UK.

The scheme is still on pause because of legal challenges, and the country’s capacity is limited to numbers far below the thousands of asylum seekers who now cross the English Channel each year.

It is unclear how the government will increase deportations without having agreements with other countries to receive asylum seekers.

Are asylum seekers required to claim asylum in the first safe country they reach?

The UN Refugee Agency has said that there is no international legal obligation underpinning the key assertion underpinning the government’s policies.

“If all refugees were obliged to remain in the first safe country they encountered, the whole system would probably collapse,” the UNHCR said in 2021.

“The countries closer to zones of conflict and displacement would be totally overwhelmed, while countries further removed would share little or none of the responsibility. This would hardly be fair, or workable, and runs against the spirit of the Refugee Convention.”

Why are so many people arriving on small boats?

The National Crime Agency and officials assess that a rise in dinghy crossings since 2018 was initially driven by government policy and increased security measures targeting migrants’ use of lorries, ferries and the Channel Tunnel.

What initially started as self-initiated attempts by migrants to make their own sea crossings, sometimes using inflatables bought in French tourist shops, was gradually taken over by smuggling gangs who spotted a lucrative gap in the market.

Numbers have exploded since the route became established as a successful method of reaching the UK, despite dozens of deaths in sinkings.

More than 90 per cent of the 83,000 people who have arrived on dinghies since 2018 have claimed asylum, and almost two thirds of the applications so far considered by the government have been granted.

Under British law, asylum can only be claimed inside the UK and there is no visa for people wanting to reach the country specifically for that purpose.

It means that people who are not eligible for limited resettlement schemes must travel independently to the country.

Home Office figures show that Afghans are now the largest group of small boat migrants, having overtaken Albanians in the autumn, while the number of Iranians, Iraqis and Syrians is also high.

Although 98 per cent of Afghan asylum applications are granted, ministers have not ruled out using the new processes against them and seeking deportations to Rwanda.

What are experts saying?

Refugee charities and experts have repeatedly called for the government to set up alternative routes that remove the demand for English Channel crossings rather than pursuing increasingly punitive “deterrents” that have so far had little effect.

Many have pointed to practical issues with the new plans, such as the limited number of returns agreements the UK has with other countries, and the fact the immigration detention estate is not big enough to hold a significant portion of small boat migrants ahead of deportation.

Yvette Cooper, the shadow home secretary, accused the government of worsening the “deeply damaging chaos” in the Channel with a failure to tackle people smuggling gangs, “collapsing” asylum decisions and falling family reunion visas.

“There is no point in ministers trying to blame anyone else for it, they have been in power for 13 years,” she added. “The asylum system is broken and they broke it.”

Ms Cooper accused the government of repeating pledges that “didn’t work” in last year’s Nationality and Borders Act, adding: “It didn’t deter anyone, even more boats arrived. What is different this time? They still don’t have any return agreements in place … this bill isn’t a solution, it’s a con that risks making the situation worse.”

Lucy Moreton, of the Immigration Services Union, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “The plans as they’ve been announced really are quite confusing. We can’t move anyone to Rwanda right now – it’s subject to legal challenge.

“We can’t remove anyone back into Europe because there are no returns agreements and we lost access to the database that allows us to prove that individuals have claimed asylum in Europe – Eurodac – when we left with Brexit.

“So, unless we have a safe third country that isn’t Rwanda to send people to, this just doesn’t seem to be possible.”

She also warned that the threat of a crackdown could lead to an increase in crossings, with gangs warning people “quick, cross now before anything changes”.