‘She paved the way.’ How a woman with big dreams broke barriers to tell Miami’s story

Bea Hines, the Miami Herald’s longest-serving reporter and columnist, couldn’t have known that on a Monday morning in January 1966, she was a handful of years away from making history in the city.

“I tell young people to never give up on their dreams. Even when it looks like they will never come true, they must hang on to them,” Hines said in an interview with the Herald this month.

“I like to tell the story of how two of my friends laughed in my face when I told them I was studying journalism. One of them said, ‘Girl, where do you think you are going to get a job in Miami in journalism?’ I learned that day, never to share my dreams with everyone because not everyone understood my dream. It was my dream to become a journalist, even when the Herald had no Black reporters. I had hope,” Hines said.

She was promoted from Herald library file clerk to reporter in the summer of 1970. And she is still writing more than 50 years later. Her column about faith and current events, written using technology that didn’t exist until decades into her career, regularly appears online and on Sundays in the Miami Herald’s Neighbors section.

Fireside chat with Bea Hines

On Thursday, Feb. 16, Hines will deliver a “fireside chat” about 14 miles north from where she made history. Down Memory Lane with Bea Hines, an event coinciding with Black History Month, is open free to the community at the North Dade Regional Library in Miami Gardens.

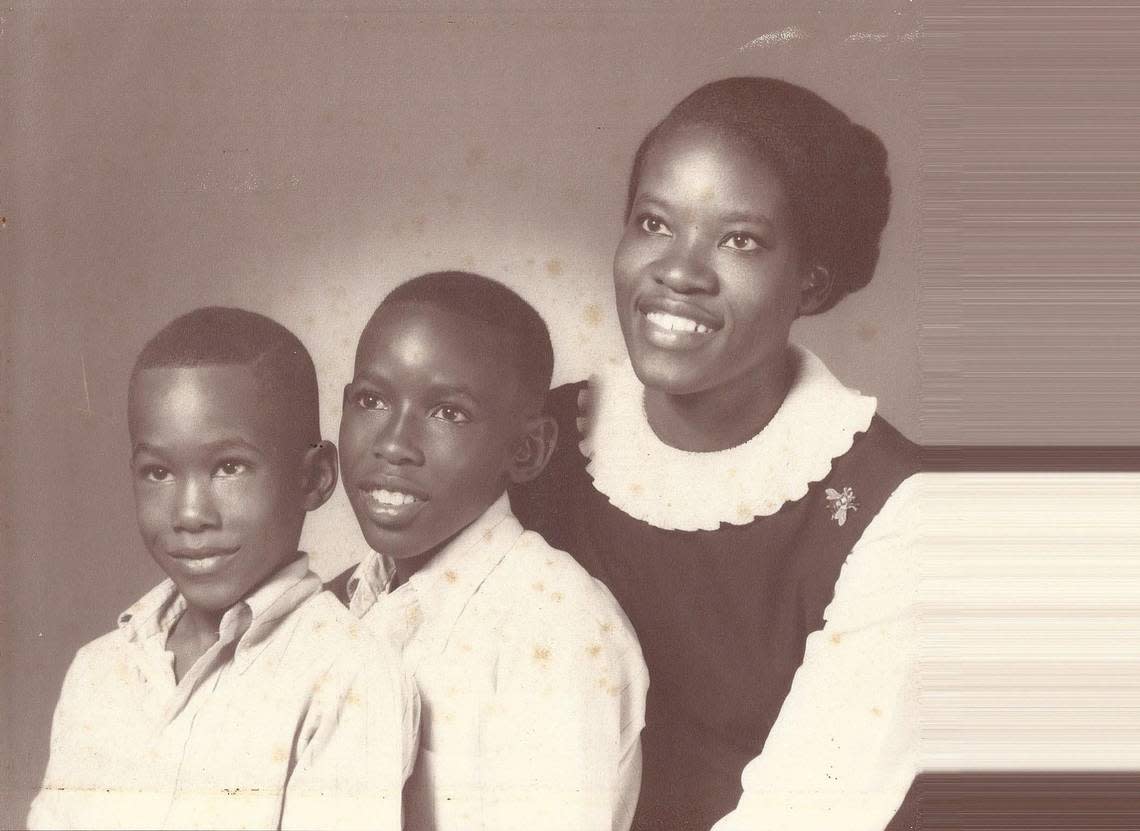

Hines will tell of how she became the first female Black reporter at the Miami Herald. She was studying nights at Miami Dade College while raising two sons in elementary school as a single parent when she earned her desired title, journalist, in 1970.

Hines may reveal why, at age 85, she has more stories to share with her readers.

On the eve of her 80th birthday, five years ago, Hines reflected on the changes and the constants of her career in a column published on Feb. 1, 2018.

Changing Miami

READ MORE: Bea Hines looks back at a lifetime filled with many changes and adventures

“Lots of things have changed since my early experiences at the paper,” she wrote, like myriad makeovers in the neighborhoods and the communities she once covered. Some, like the building that let a 29-year-old Black woman get beyond its imposing heavy brushed steel and glass doors and have a public voice in the days of segregation, are but memories.

“Even as I write this, my childhood home — the Liberty Square Housing Project (known in its last years as the Pork ‘n Beans Project) — is disappearing a bit more each day. It is being demolished to make way for a new neighborhood. Back in the day, when I was a child, Liberty Square had the only playground in town for Negro children. There were slides and swings, you name it,” Hines wrote in her warm, embracing conversational style.

“A great Sunday outing for us would be taking the Route 21 bus to Liberty City after church and spending the day standing in line for a chance at one of the few swings. We didn’t mind. The wait would be worth it when we’d be pushed to the limit by a friend, our skinny legs pumping through the air. It felt like we were going to touch the clouds,” Hines wrote.

That joyous sensation we seem to only allow ourselves to fully experience in childhood still burns inside Hines today.

“Every time I sit at my computer, and start to write, I feel like I am touching the clouds,” Hines said in an interview with the Herald this month. “I feel that way because, never in my wildest dreams as a child did I think this dream that I am living now could come true. I feel so blessed that I am still doing what I truly love,” Hines said.

“When I walked through those double doors to enter the Miami Herald building on that first Monday of January in 1966, I was walking on cloud nine. I knew my life was changing. I just didn’t know the extent to which it would change. And, yes, I am still floating on cloud nine, just as I did as a child soaring in the air on that Liberty City swing. Through all the ups and downs, this has been a great journey,” Hines said.

A role model

Monica Richardson, vice president of news for large markets for parent company McClatchy and former executive editor for the Herald, remembers the welcoming embrace she received from Hines on her first day leading the Miami newsroom in January 2021.

Richardson shares a kinship. She was the first Black executive editor in Herald history.

“The year that Bea became a reporter — 1970 — is the same year I was born. When I joined the Herald two years ago she was one of the first to welcome me to South Florida. Over a soul food lunch, we talked about her journey and her coconut cake. In Bea, I’ve always known I have someone here for support and encouragement. When I call she answers,” Richardson said.

“Bea is an inspiration not only to generations of Black journalists but to humankind. She paved the way for journalists of color, women and others who may have thought their dreams were unattainable. Bea defied the odds and overcame obstacles known, and unknown,” Richardson said.

Hines, a Class of ‘56 Booker T. Washington Senior High School grad, is aware of her legacy.

“I live Black history everyday,” she said. “There is not a day that goes by that I don’t think about where I am today and how far I have come. ... I have seen a lot; heard a lot and lived a lot. And as the old gospel song goes, ‘I’m not tired yet.’

“It amazes me that I have lived to witness so many changes in the country and in our community. And yes, even in our newsroom at the Herald,” Hines said. “When I became a reporter, the newsroom was not a welcoming place for women. And here I come — a Black woman! Just amazing!”

Civil rights era

When Hines first joined the Herald, the struggle for civil rights was entering its most tumultuous era.

About six months before the Williston, Florida-born Hines was hired, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in Aug. 1965. That law’s intention was to overcome legal barriers that kept African Americans from exercising their right to vote despite its guarantee under the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

About two years later, Martin Luther King Jr., was killed on a Memphis balcony on April 4, 1968.

Why Hines writes

READ MORE: How these six women became matriarchs of Black Miami

Hines, who acknowledges the inspiration and grace and strength she gleaned from her mother, Ida Belle Johnson, said she never thought much about having something so lofty as a public voice.

“When I write,” she said, “I try to feel the pain and victories of the people I am writing about. I always try to put myself in the place of those I write about. So, in a sense, I guess I am somewhat of a ‘public voice.’ I hope my readers will see my heart. I want them to know that I really care — about our country, about our community. I want them to know that I really want us all to come together as one nation [and] community. That’s what drives me.”

Before the Herald hired Hines, she worked as a maid in 1960s Miami. “I wasn’t treated very well and I had to work hard to keep up my self-esteem,” she said.

Hines’ empathetic voice came honestly — even if it caused her some initial trepidation.

“I think the hardest story I ever had to write was one of my first stories,” Hines shared.

“I was sent to cover a family whose little boy, who was 5, was leaving home to die. He had a brain disease. I remember writing that while his little playmates were leaving home for their first day of school he was leaving home to die. I remember crying. Right there on the job. I was told that reporters had to have tough skin. Well my skin wasn’t so tough and when I got back to the office, I decided I’d tell the editor about my reaction before anyone else did. I confessed to Ben Burns that I cried on the job. He told me that my sensitivity was what made me a good writer,” Hines said.

“Her reporting and her columns have always been told from a place of truth, compassion and realness that anyone can relate to,” Richardson said.

“Bea Hines is a treasure in this community and our newsroom,” said Jeff Kleinman, Miami Herald day editor and the Thursday evening event moderator. “I want everyone to know Bea’s story: how she became a trailblazing journalist here and what she went through in Miami and in the newsroom. We’ll be chatting all about that on Feb. 16. She is the heart and soul of Miami and the Herald.”

If you go

What: Down Memory Lane with Bea Hines. A fireside chat in honor of Black History Month with Miami Herald columnist Bea Hines and editor Jeff Kleinman.

When: 6-8 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 16.

Where: North Dade Regional Library, 2455 NW 183rd St, Miami Gardens.

Cost: Free. Tickets available via EventBrite.

Houses of worship are ‘community centers’ in Miami, a way of life for Herald columnist