She once worked in healthcare, but now twin teenage daughters require all her time

Tucked in the far right corner of Rachel Jean-Marie’s living room is a stack of folders containing medical records for her daughter Darchelle. The 18-year-old has been in and out of the hospital for the past six months, her most recent visit the week of Thanksgiving.

As Jean-Marie told it, Darchelle’s glucose levels decreased drastically, which led to a hospital stay of more than a week. They are used to the hospital visits: Darchelle has been in and out of them since she and her twin sister, Soraya, were born prematurely at 32 weeks weighing just three pounds.

The twins faced challenges early on: Soraya needed surgery as a baby due to the holes in her heart; she was diagnosed with cardiomegaly — an enlarged heart — as a result. She also had difficulty crawling and needed to be fed through a tube.

Darchelle had speech and language issues, which still persist today.

The girls required occupational, physical, and speech therapy.

While Soraya eventually overcame early challenges, she was later diagnosed with a learning disability that affects her ability to process abstract concepts, such as sarcasm.

Darchelle’s circumstances are far more challenging: In 2016, she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder bipolar type (OCD/anxiety), which causes psychosis and hallucinations. Before that, there were diagnoses of bipolar disorder at 13 and autism at 11.

The multiple diagnoses contribute to Darchelle’s speech and language difficulties. At times, she needs help dressing and bathing herself, and eventually required around-the-clock care.

Jean-Marie, 44, had primarily worked as a respiratory therapist until February 2021, when she quit her job to care for her daughter full time. “I think when you live like this, you’ve been in a crisis all your life, you don’t even know that you’re in a crisis,” Jean-Marie told the Miami Herald. “You don’t even know that you are actually surviving. You start disconnecting with people.”

Without the income from a full-time job, Jean-Marie struggles to pay for basic expenses like rent and groceries.

“She’s a strong mom. She tries to stay positive, and she has a lot going on with her children’s needs,” said Danielle Leys, an outreach coordinator at Parent-to-Parent.

So Leys looked for ways to take pressure off Jean-Marie, including nominating her for Wish Book to help ease some of her financial burden.

For more than a year, Leys has assisted Jean-Marie with getting Darchelle reenrolled in public school and provided emotional support.

“I’m not a counselor, but I am a parent to a child with special needs myself. And so I try to be that shoulder to cry on and listen to,” Leys told the Herald. “As for Darchelle, I try to support her by reminding her how wonderful she is and trying to share resources like activities (and) events that she can participate in to be more involved.”

Early Intervention

Jean-Marie first noticed the girls’ developmental challenges when they were in the first grade, but assumed they were mostly due to being born premature. She had the girls tested to put them on Individualized Education Programs at school; that’s when she learned they had a “developmental delay.”

Darchelle had speech difficulties. She “couldn’t say a word, she was pointing,” Jean-Marie said. “She’ll get mad when she cannot explain herself.”

At that time the girls, about 5 or 6 years old, were enrolled in a public school. “I asked to sit in the classroom, and I realized that Darchelle was fumbling around when the other kids the same age were able to follow through and pick up their book, look for the page and follow,” Jean-Marie said.

As the two grew older, Jean-Marie noticed intellectual and behavioral difference between the girls. She later moved them to other schools — sometimes private schools — that seemed better tailored to their needs. Sometimes both went to the same school, other times they went to different schools.

At times Darchelle’s school called Jean-Marie daily about her daughter’s behavior.

“Every time she (had) challenges with math or any kind of subject, Darchelle never accepted that she did not know,” Jean-Marie said. “So, she got frustrated and here comes the outbursts or tantrums.”

Later, a full psychological evaluation found Darchelle had a low IQ, at which point she was diagnosed with an intellectual disability. As the years went by, Jean-Marie learned Darchelle had autism, although she described the diagnosis as “not as severe.”

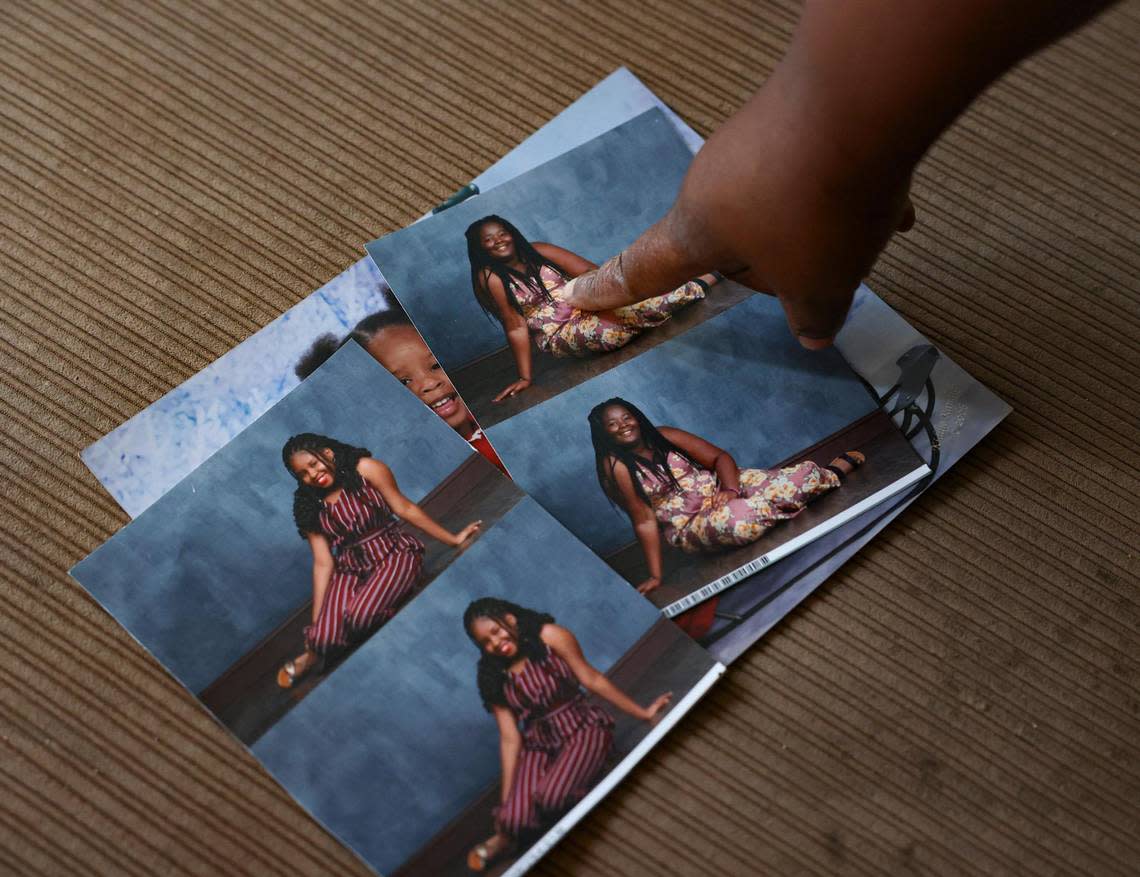

With Soraya, it was a different story: The A-student is a hard worker who juggles several extracurricular activities. “Soraya has that personality, she just glows. She’s very motivated,” Jean-Marie said.

Jean-Marie admits she was initially in denial when asked on questionnaires about the severity of some of Darchelle’s behaviors, assuming it was a phase that she would outgrow.

“But as years go by, you realize that there’s something wrong, and yes, divorce did set in. A lot of those things that Darchelle was displaying, I thought it was a separation issue,” she said. “So, I kept going to therapists for family issues and not knowing that there was something else.”

A Balancing Act

A typical day when Darchelle is not in the hospital starts as early as 6 a.m., with Jean-Marie cooking breakfast, getting Darchelle dressed and prepared for school, and ensuring she takes her medication.

Jean-Marie takes the girls to their respective schools and returns home to follow up with emails and phone calls concerning Darchelle, often regarding insurance, Individualized Education Program meetings, or her medications. If she finishes early and Darchelle’s school doesn’t call, Jean-Marie cleans the home. Then she takes Darchelle from school to the library, one of the few places where her daughter socializes. There, she and her therapist go over homework and other skills. She also participates in the YOUmedia digital-media program offerings where teens can learn skills such as podcasting and photography; Jean-Marie said Darchelle likes to create 3D animations.

This schedule doesn’t account for Darchelle’s elopements, or leaving the house without permission.

“It’s not uncommon when you have kids with autism and low IQ that they have that kind of behavior,” Jean-Marie said. “She’s eloping more every time she’s mad. It could be for something very simple.”

Worrying about Darchelle’s safety is part of the reason Jean-Marie sleeps in the living room on the sofa: “I have to know when she wakes up because she will wake up in the middle of the night and hear voices telling her to get out.” But for the past six months, most of Jean-Marie’s time has been spent at the hospital with Darchelle.

At the same time, she tries to ensure Soraya is cared for and maintains her grades in school. The high school senior is involved in several organizations including the National Honor Society and student government, and she loves acting in school plays. She is also advocating that her school have an autism week to educate students about it and destigmatize it.

At some moments, it is Jean-Marie who relies on Soraya. The morning of Jean-Marie’s interview with the Herald, Soraya gave her mother a small pep talk: “‘Just understand that so many parents are going through it,’” Jean Marie recounted. “‘So at least they will find out’ and she said, ‘that’s what I live for.’”

Seeking Resources

With Darchelle’s diagnoses worsening and without a job, Jean-Marie relies on Medicaid and other government assistance to pay Darchelle’s hospital bills. But everyday expenses such as groceries, gas, and bills have mounted, leaving her stretched thin.

“I think the biggest challenge is not being able to get the resources to get what they need, and you always feel like you’re fighting for everything,” she said. The trio live in a one-bedroom apartment where Jean-Marie sleeps on the sofa — not a sofa bed — in the living room. She sobbed while sitting on the sofa. “I think that’s where it gets very difficult.”

Leys described Jean-Marie as a very humble person who doesn’t like to ask for help. “But she deserves the help because she’s taking on a lot: raising two beautiful children who require a lot of mental and emotional support.”

While Leys considers her a “warrior mother,” she acknowledges Jean-Marie needed a lot of help. “Because resources sometimes are difficult to find to help Darchelle with her needs, it’s taken a toll on her. And so as a community, we could help to relieve a little stress off her, bring joy into her life. That would be great.”

Jean-Marie is asking for: an alarm and security camera due to Darchelle’s constant elopements, a sofa bed for herself, a tablet or iPad for the girls to do their schoolwork, a television for the girls’ room, referral to a guardianship attorney who will do pro bono work, debt assistance, and gift cards to pay for gas, groceries and Christmas gifts.

When you walk into Jean-Marie’s home, her hospitality hides her daily struggles: She offers you a cup of coffee. If you don’t want that, she’ll offer you a cup of tea or some water. She’ll even offer juice and a bite to eat. With her warmth and welcoming demeanor, you wouldn’t know how much being a parent to children with developmental disabilities weighs on her.

Grant a wish. Make a difference.

How to help: Wish Book is trying to help this family and hundreds of others in need this year. To donate, pay securely at MiamiHerald.com/wishbook.

She worries about the future — particularly Darchelle’s future.

“What’s going to happen when I’m not there?” she said of Darchelle. “Who’s gonna take care of her? And as she gets older people get more afraid.”

She worries about the people who will judge Darchelle, noting that society often does that to others and especially people with disabilities. She worries even more when she won’t be able to protect her.

“I can no longer shift the conversations to cover the fact that she might not be able to understand because of her level of intellect,” she said between sobs. “All I want to do is to be able to be there for her, make sure that she has some type of normal life and now it’s getting more difficult.”

How to help

To help this Wish Book nominee and the more than 100 other nominees who are in need this year:

▪ To donate, use the coupon found in the newspaper or pay securely online through www.MiamiHerald.com/wishbook

▪ For more information, call 305-376-2906 or emailWishbook@MiamiHerald.com

▪ The most requested items are often laptops and tablets for school, furniture, and accessible vans

▪ Read all Wish Book stories on www.MiamiHerald.com/wishbook