A Shadow of the Black Death Has Reappeared in the Pacific Northwest

While rare, the bubonic plague still infects more than a handful of humans each year in the United States.

The once-deadly disease known as Black Death is typically transmitted to humans via flea bites.

This is the first case in Oregon in eight years, and is tied to an infected pet cat.

A disease doesn’t get the named Black Death for nothing. Infamous for wiping out roughly a third of Europe’s population in the 14th century, the bubonic plague has recently been largely kept in check thanks to modern antibiotic medicine. But that hasn’t stopped the plague from appearing in humans in the United States annually, with the latest case coming from Oregon.

A rural Deschutes County resident was likely infected with the bubonic plague from a heavily symptomatic pet cat with “a fairly substantial” infection, Richard Fawcett, health officer for the county told NBC News.

The bubonic plague is usually transmitted to humans via flea bites. And cats, such as in the recent Oregon case, are a common culprit. Fleas and rodents are the most likely carriers of the plague, and cats interact with both. The plague can also get passed through bodily fluids, which just may have been the case in Oregon, considering there was a sick cat with a draining abscess in the equation.

The infection starts in the lymph nodes, which is where the plague gets its bubonic name. In the Oregon case, the infection had reached the bloodstream before hospitalization. Fawcett said the patient “responded very well to antibiotic treatment.”

But that doesn’t mean everyone is in the clear yet. The patient may have developed a cough—a potential sign of the pneumonic plague, the version of the plague that transmits human-to-human. Health officials in Deschutes County gave antibiotics to the patient’s close contacts.

“If we know a patient has the bacteria in the blood, we might decide to be on the safe side,” Fawcett said.

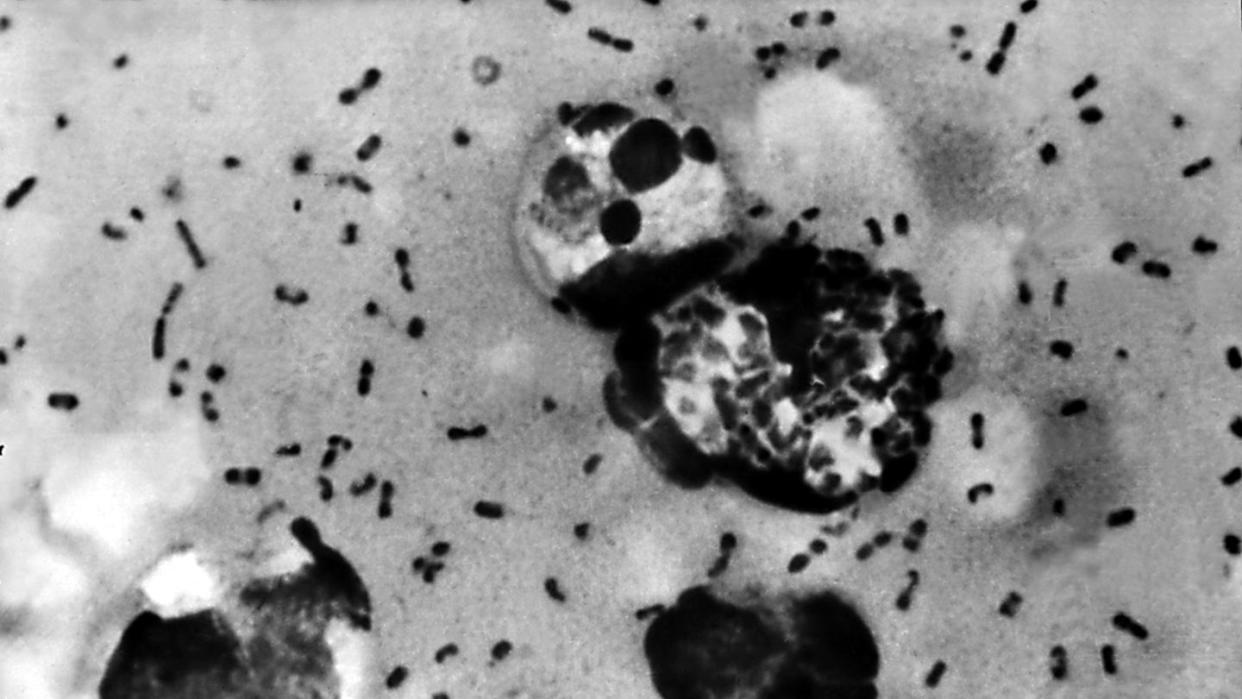

When the plague is introduced to the body (typically through a bite), the bacterium Yersinia pestis travels through the lymphatic system to the nearest lymph node, and replicates itself, according to the World Health Organization. The lymph node then becomes inflamed and painful. Human-to-human spread of the bubonic plague is rare, but if the plague advances to the lungs, it can turn into a more severe case of pneumonic plague. That version is both transferable between humans and more deadly.

The CDC reports an average of seven plague cases annually in the U.S. over the last few decades, with the most coming from New Mexico. Cases are typically centered in two regions—either New Mexico, northern Arizona, and Colorado, or California, southern Oregon, and western Nevada.

“It’s the same thing that caused the Black Death, but that was in the pre-antibiotic era,” David Wagner, director of the Biodefense and Disease Ecology Center at Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, tells NBC. “Now it’s very easily treated with simple antibiotics.”

More than 80 percent of plague cases in the U.S. are bubonic and confined to the lymph nodes. Of the seven average cases annually, they almost all comes from the rural wilderness of the West. The last case in Oregon was in 2015, attributed to a flea bite on a hunting trip. Of the nine cases reported nationwide in 2020, two lead to deaths.

The plague killed over one third of the European population in the 1300s and came back again, both in Europe and China in a second wave. It returned again (largely in Asia) in the 1800s, and continued to spread to India and eventually San Francisco. Introduced to the U.S. in the early 20th century via rats on ships carrying the plague, the last time the plague turned into an epidemic in the U.S. was in the 1920s.

You Might Also Like