The Secret X-Factor That History's Strongest Men Have in Common

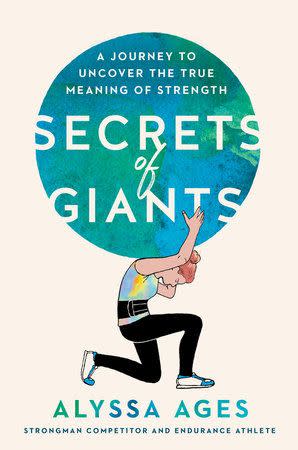

The following is an excerpt from Secrets of Giants, a new book that documents a journey into the depths of the strength training world to answer the question: What if strength isn’t about how much we can lift, but how we manage life’s struggles? Author Alyssa Ages interviewed more than 75 athletes, coaches, psychologists, and researchers to uncover the power of pushing our limits.

THE PURSUIT OF STRENGTH has never really been about a great set of biceps or six-pack abs. It’s about the way being strong makes you believe you can accomplish anything.

While the drive to look better in a t-shirt is often what compels us to pick up a set of dumbbells, it’s rarely what keeps us coming back. That desire to not only be powerful, but to also be recognized as powerful is what compels so many strength athletes to pick up a barbell for the first time.

Picture the fictional superheroes (and villains to an extent) you admired in childhood, and their spandex-busting brawn: muscle is a signifier of toughness, power, and invincibility. It gives the appearance of a layer of distance between the owner and anyone who would seek to harm them. That’s a compelling goal for anyone enduring adversity.

Beyond appearance, strength provides the sensation of possibility; the first time I picked up an Atlas stone that seemed immovable, I was overwhelmed by a sudden sensation of fearlessness, like I could overcome anything that stood in my way.

“There's a stability in weight training that seems to anchor people and help them get through [difficulty],” explains Dr. Conor Heffernan, a lecturer in the sociology of sport at Ulster University.

Secrets of Giants: A Journey to Uncover the True Meaning of Strength

penguinrandomhouse.com

$28.00

Given my own experience turning to weights to overcome feelings of vulnerability and weakness, I wanted to know just how pervasive that notion is among lifters. What I found was that from the turn of the century to the mid-twentieth century, this was the dominant narrative, and likely one that let subsequent generations know that no matter your circumstances, it was possible to literally lift yourself up through strength training.

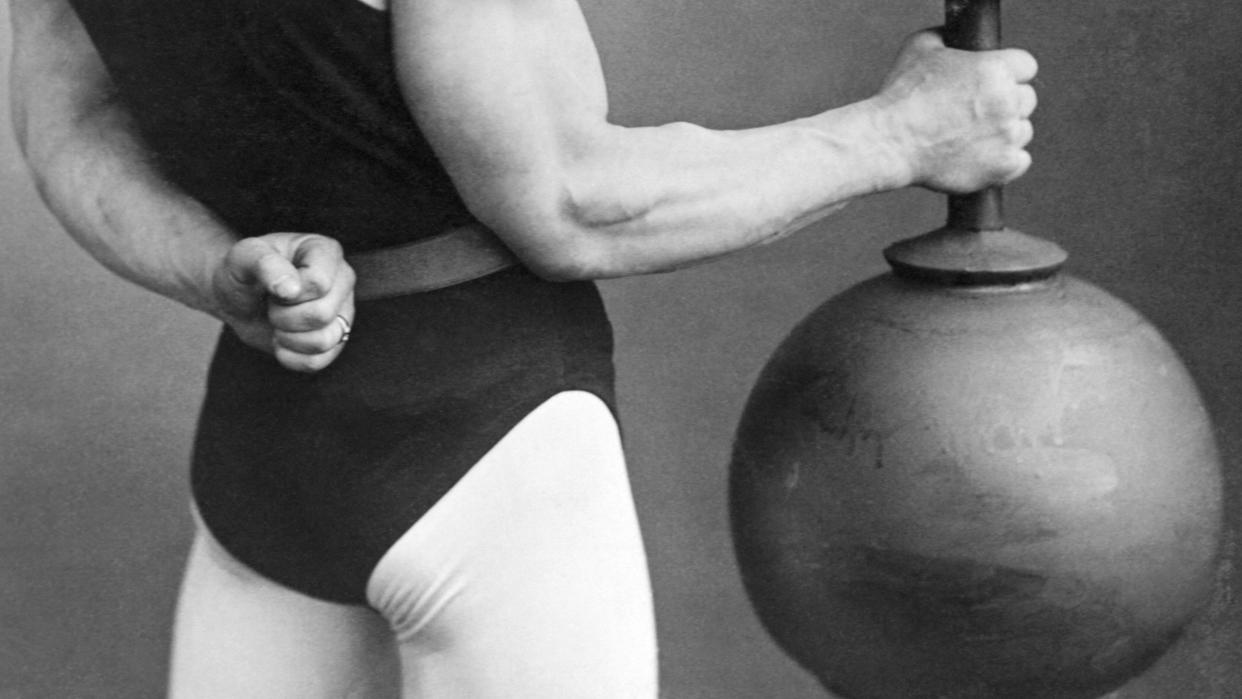

Though as an adult he was upheld as the ideal of human perfection and the father of modern bodybuilding, Eugen Sandow claimed in his biography that in his youth he was weak and frail. “As a child, I was exceedingly delicate,” he wrote. Inspired by statues of Greek and Roman gladiators, he began to explore fitness, building his revered physique and ultimately selling his own system of training with the messaging: you can do this, too, you can be like me.

Sandow was eventually so admired for his bodybuilding acumen and aesthetic that he was featured in one of the first films Thomas Edison ever made, flexing and posing in a pair of white briefs.

Joseph L. Greenstein, later known as The Mighty Atom, was born premature at only 3.5 pounds, too weak to cry. When he was fourteen, he overheard doctors telling his mother that his asthmatic condition appeared to be congenital and that he wouldn’t live past his eighteenth birthday. On the way home from the doctor, Greenstein was captivated by a poster of the champion wrestler Volkano, who looked every bit what Greenstein was not: strong, healthy, capable. He snuck into the circus tent and was taken in by Volkano, who brought him on the road and trained him. “The greatest athletes have grown from being weak and infirm,” Volkano says. “Do you want to die?” Greenstein would go on to become one of the world’s strongest men, bending steel with his bare hands, biting through nails, and once stopping an airplane with his hair. Many believe he was the inspiration for Superman.

Milo Steinborn, who would become a professional wrestler and world-record-breaking weightlifter, developed his interest in the pursuit of strength while in a German internment camp for four and a half years during World War I.

Alan Mead lost a leg below the kneecap in World War I and then took up physical training to regain his strength, becoming a bodybuilding phenomenon in the 1920s, revered for his ability to persevere through adversity.

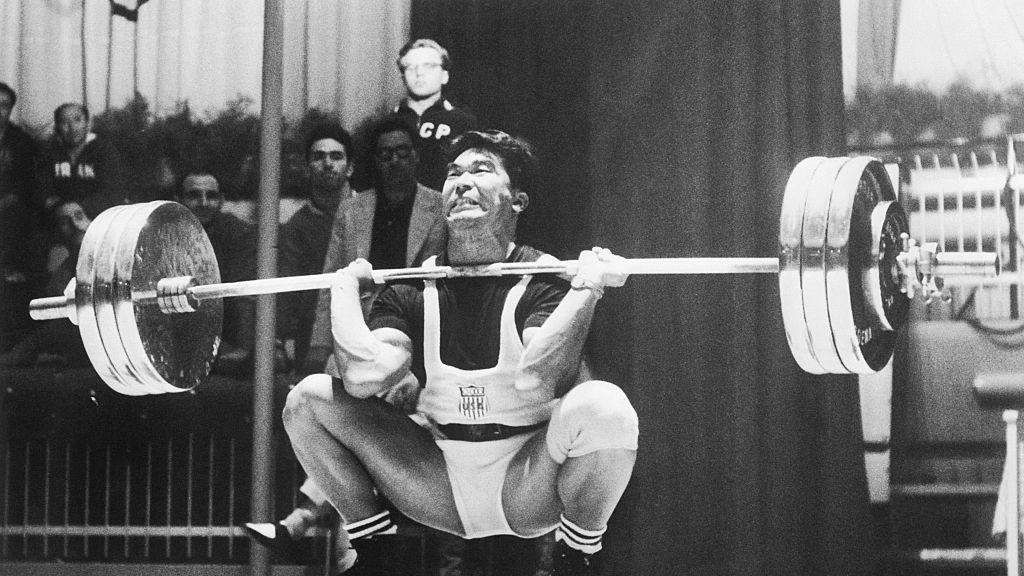

At age eleven, Japanese American Olympic medalist Tommy Kono weighed just 74 pounds and was so ill he missed a third of his schooling. He sent a postcard for information on the Charles Atlas bodybuilding course but couldn’t afford to enroll. While being held along with his family and 120,000 other Japanese Americans at the Tule Lake internment center during World War II, Kono was given a barbell by a neighbor who introduced him to weightlifting. He had put on 15 pounds by the time he and his family were released. “I didn’t want to be a weightlifter,” Kono recalled in 1960. “I just wanted to be healthy.” By the time he retired in 1965, he had established seven Olympic, thirty-seven American, eight Pan American, and twenty-six world records.

“His family had nothing, and he had nothing,” his biographer, John D. Fair, an adjunct professor in the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education at the University of Texas at Austin, told me. “He was weak, he had asthma. He built himself up and eventually he became, as I call him, the strongest man in weightlifting.”

Decades later, the desire to build strength not just to improve aesthetics but to overcome vulnerability is still the most common narrative used to explain why people get into strength training.

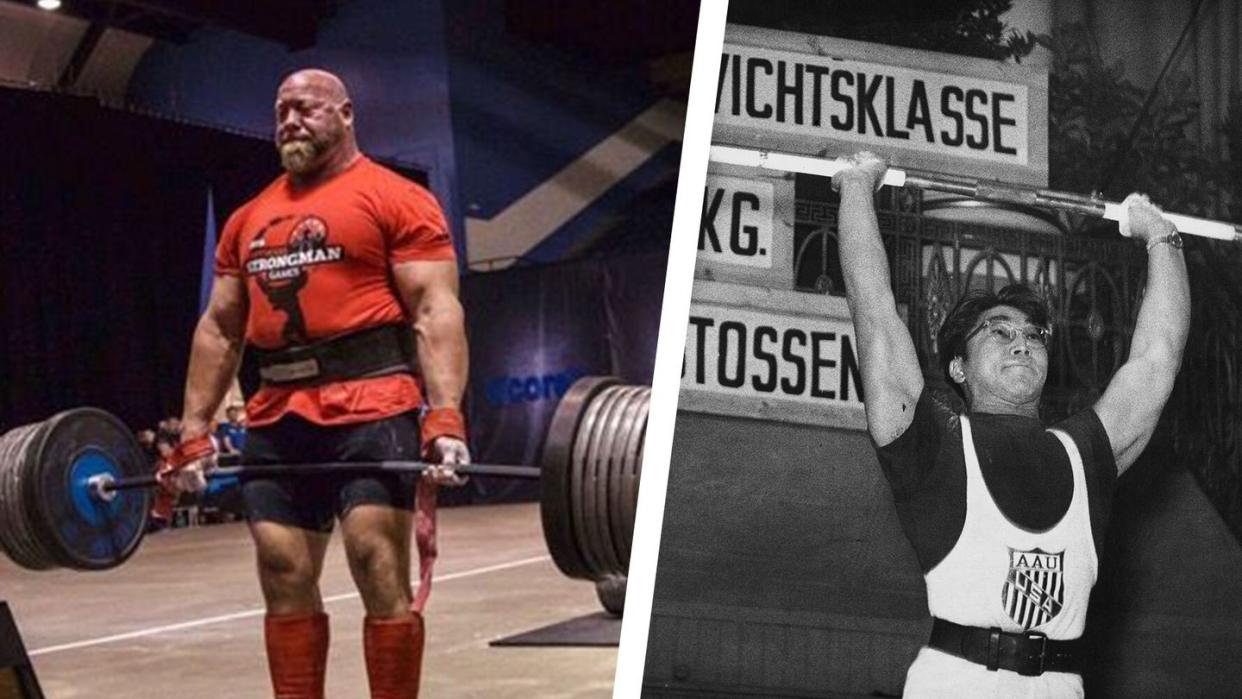

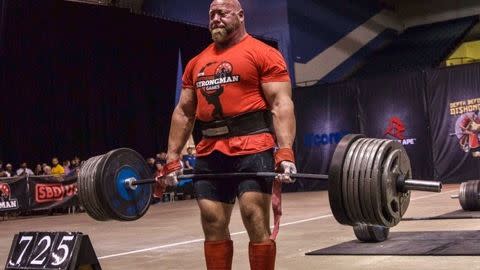

Maybe it says more about my own biases or my being raised in the eighties with the image of the gym rat as the unemotional “I lift things up and put them down” meathead, but I wasn’t prepared for one of these stories to come from ten-time World’s Strongest Man competitor, Masters World’s Strongest Man, and owner of a farmer’s walk world record (275 pounds per hand, for nearly 250 feet, in 47.3 seconds) Nick Best, who at fifty-three is still built like a comic book villain, with a bald head, a manicured dirty- blond goatee, and a six-one, 300-pound frame.

I was leaning on a concrete barrier in the parking lot outside of the Official Strongman Games arena in Daytona Beach, interviewing the founder of the Giants Live strongman arena series and former World’s Strongest Man competitor Colin Bryce, when Best walked over. He was on his way to join fellow pro strongman Evan “T-Rex” Singleton to watch Disturbed play the Rockville festival at the Daytona Speedway (and yes, they were planning to hit the mosh pit).

Throughout my interview with Bryce, athletes had been popping by to recap their performance or snap a photo with him, but when Best came by, Bryce nudged him to get more involved.

“Why did you get into strongman?” Bryce asked him, pulling him into our interview.

There was a long pause and we both noticed Best was starting to tear up.

“Well, that’s hard to say,” Best began.

“That face says it all,” Bryce noted.

I’d seen Best lift a 1,450-pound Viking ship mast on his back and raise 2,791 pounds from the ground using just his legs, beating three guys more than a decade younger than him on the History Channel’s The Strongest Man in History. I’d watched videos of him lifting more weight on a single barbell during a casual home gym training session than I could move in all my personal record lifts combined. So seeing him overtaken with emotion was disarming.

“I got into it because I wanted to play high school football. But I also had a stepdad that was pretty abusive. I wanted to make sure nobody could do that to me.” He paused to compose himself. “So I got bigger and stronger. And it didn’t happen anymore. And I just kept doing it because no one was ever going to do that to me again.”

He went into powerlifting, winning six consecutive California state championships (and seventeen meets overall), logging the first drug-free 800-pound squat in the state’s history, and hitting the first drug-tested 2,000-pound total (total pounds lifted in the three events: back squat, bench press, deadlift) in California history. Two years after making his way to strongman, he broke the world record for the farmer’s walk.

In addition to giving him greater courage, lifting also taught him discipline, something he’s taken into his life outside the gym. “If I’m going to learn something, I’m going to learn it from top to bottom, front to back, and I’m going to follow the order you need to do things,” he said. “And if it means I don’t go somewhere and do something so I can train back home, so be it. I’m going to have the discipline to put that kind of focus and effort into whatever it is I decide to do.”

Listening to Best, Bryce suggested that people often come to lifting with something to prove. “Maybe it’s a negative driver,” he said, “but how many people who don’t get into lifting also have a negative driver? I think the reason you often hear this story with lifting or sports or boxing is because it is a positive story at the end.”

Best agreed. “Every opportunity you get is what you make of it, and even if you have ungodly negative things happen in your life, you’re not a victim,” he said. “You’re a victim when you give up. You’re a victim when you let that define you. You’re a victim when you don’t do something about it. You’re a victim when you want to sit there and get something for nothing just because something bad happened to you. And I’m not going to be that. I’m going to go be the best I can be.”

You Might Also Like