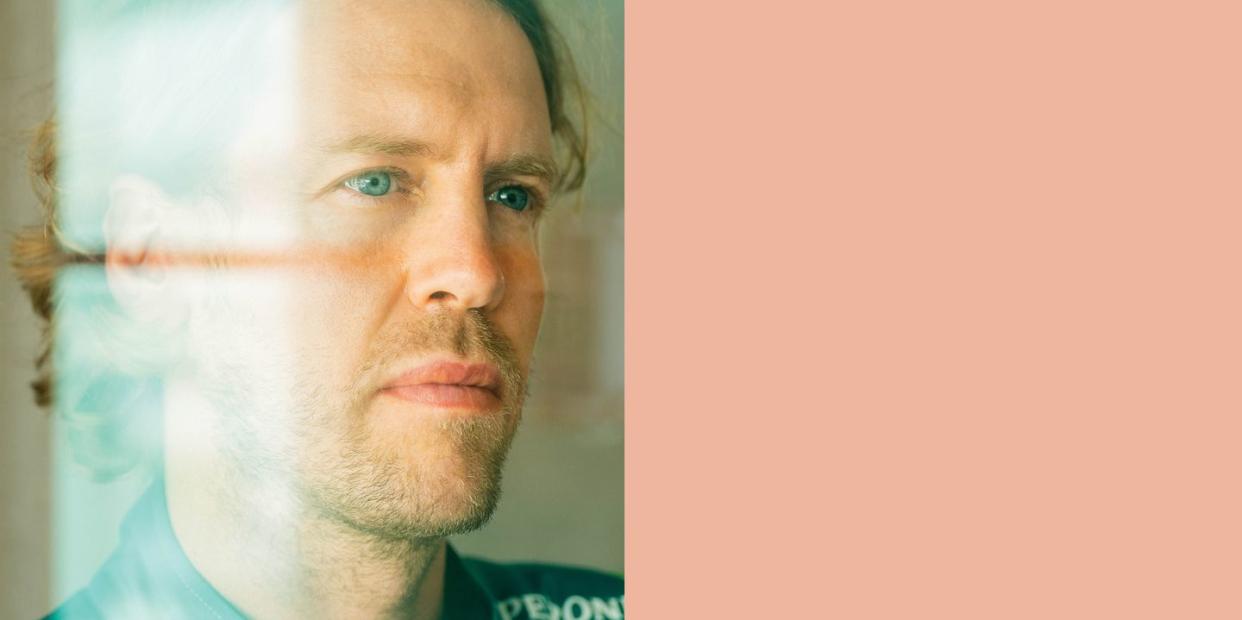

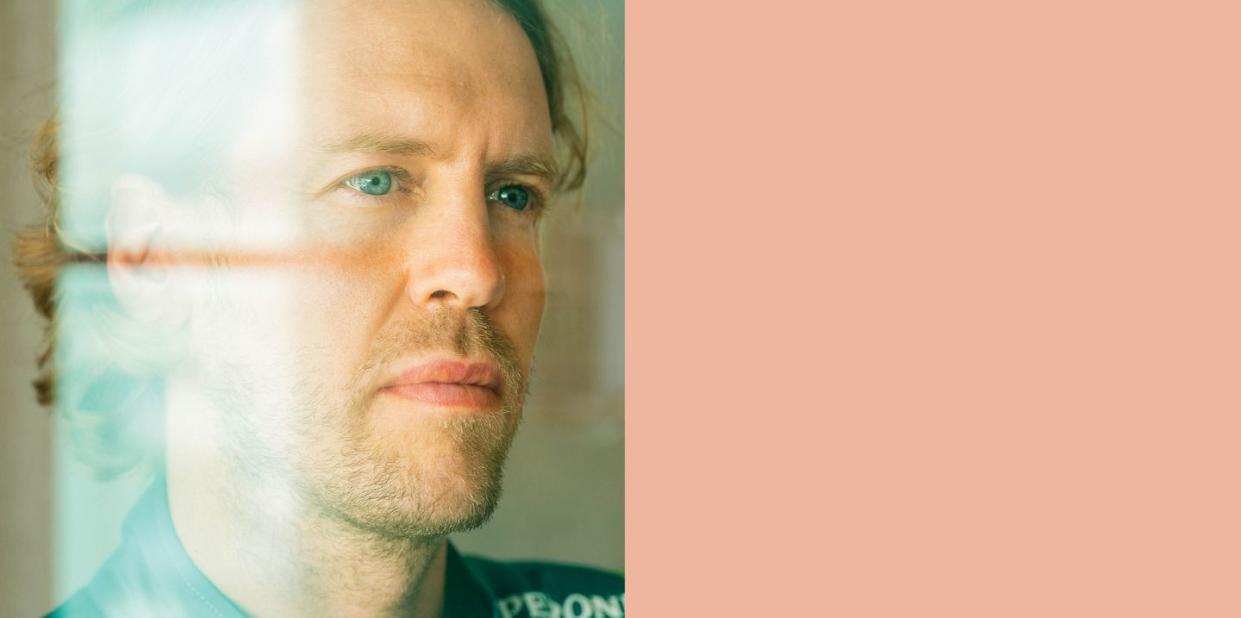

Sebastian Vettel Wasn't Raised Like Other F1 Champions and He Isn't Retiring Like One, Either

“What is an activist?” asks Sebastian Vettel. He’s scratching his scruffy face and grimacing, bristling at the accusation that he has become one. It’s hard to argue against it: Over the past couple of years, even as he’s struggled to find top-10 finishes with the Aston Martin Cognizant Formula One Team, Vettel has become the sport’s loudest voice on topics many racing fans won’t appreciate: civil rights, boycotting Russia, the plight of underprivileged children, the burdens placed on the Global South, and, most significantly, climate change, which he believes is linked to everything.

This story originally appeared in Volume 13 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Certainly, Greta Thunberg is an activist, I propose.

“I don’t know,” he offers. “Is Greta an activist, or is she just a very concerned citizen of our planet?”

We’re sitting in Aston Martin F1’s paddock at the Hungaroring outside Budapest, a few days before the Hungarian Grand Prix. In the history of strange conversations with F1 champions, this is up there with an impromptu exchange I once had with Michael Schumacher in a Monaco alley, about the orange stitching on my brand-new pair of Adidas. (“How very flashy,” Schumacher said, smiling. “Can I buy a pair nearby?”) Except this conversation is deep, elemental. I knew a bit about Thunberg, the young Swedish firebrand who has become one of the world’s foremost advocates of climate-change awareness. But I didn’t anticipate that Vettel would know everything about her.

SIGN UP FOR GRID NOTES, ROAD & TRACK'S NEW MOTORSPORTS NEWSLETTER.

“Greta has Asperger’s syndrome,” Vettel says. “For her, what’s so confusing—and also so sad—is that I think she’s just very honest about what she feels.” He views it as related to her condition. “For her, our inaction on the climate crisis just doesn’t make sense, because it doesn’t make sense. And whereas everybody else is sort of numb to it—we have lives, we have things going on, we have other interests, and all of that—she is just being logical. ‘Why do I need an education when the world is going to be uninhabitable?’”

Strangely, Vettel’s take on Thunberg shows what made him such a special driver. He is absolutely ravenous for information. He is a rabbit-hole specialist. When he has a curiosity, he will not stop until he can see every side of it. The rabbit hole he can’t get out of right now, and that he can’t resolve, is climate change—which, when you think about it, is a terrible irony, given that he is a star figure in a global traveling circus centered around burning fossil fuels to achieve speed and glory.

This is part of the continuing transformation of Sebastian Vettel. Over his career, he has appeared to fans in many forms: prodigy, brat, champion, jester, provocateur, outsider, mentor, scold, and, finally, agitator. When he gets on a roll talking about e-fuels and carbon credits, he is indistinguishable from crusty protesters marching across Washington Square and shouting doom.

“You look like a hippie to me,” I tell him. His long, stringy hair is just a few hours short of greasy. He’s pushing it out of his eyes as he talks, though careful not to push it too far. “I have a lot of hair, yes,” he says wistfully, then gestures to his receding hairline. “But in significant ways, I don’t have a lot of hair. It’s a privilege of aging.”

Just minutes before this conversation (one of many we would have), with no warning to just about anyone, Vettel announced his retirement. He told his Aston Martin F1 bosses, as well as his assistant, Britta Roeske, who, though not surprised, was a bit shocked that it happened on this day. He leans in and whispers to me, “Do you know I’ve just announced my retirement? Your timing is perfect.” While we are chatting, his retirement video—a stark, honest, and completely unvarnished appreciation of the sport as well as a call to action—is playing out like a grenade blast on his Instagram account.

He’s right; the timing is perfect to reconsider the life and times of a champion. Now 35, a happily married father of three, Vettel is at the end of his F1 career. At his peak, he was as untouchable as any driver in any era of any series. Love him or hate him, and there are millions who go both ways, he will go down in history among a class of drivers so elite, they have names like Schumacher, Hamilton, and Prost—and, arguably, no one else.

Vettel came from a middle-class German suburb whose name doesn’t register unless you’re from there. His father, Norbert, was a carpenter and a kart-racing hobbyist, though he never pushed Vettel to be anything other than his own person.

“I didn’t understand at the time how lucky I was,” Vettel recalls. “I mean, compared to many other drivers, I am an exception. I had a normal childhood. I raced, and I was gone every weekend, but when I wasn’t gone, I was at home. I went to school, I finished school, I finished high school. I did karting, and I think I was as professional about it as a child can be. But the moment I got out of the go-kart, I was in the dirt, I was in the forest.”

Red Bull Racing talent scout Helmut Marko compares Vettel’s upbringing with Max Verstappen’s as a study in contrasts that led to similar results. Max’s father, F1 vet Jos Verstappen, was notoriously cruel to Max as a kid, forcing him to race in conditions that a 10-year-old should probably not have to endure. Vettel was allowed to come in out of the rain.

“What do we think makes someone more resilient?” Vettel wonders, as he ponders Max’s extremely promising career. “I didn’t get beaten up. But if you do get beaten up your whole life, does that work? Or does it work to be loved and explained the ways of how the world works? If you compare the two, who is more resilient? Is resilience fighting back—like somebody hits you, you hit back? Or is resilience strength in understanding what just happened, reflecting and taking things on from there?”

Though he’s making a rhetorical point about a racing driver, he’s much more interested in how resilience applies to his own life after retirement. “Being a father myself, obviously I have these challenges every day,” he says. “And if you say, okay, my children are allowed to talk back, well, then you also need to face the fact that they are talking back. So I think it is fascinating, because it’s so much of who we are later on and how we manage situations. And I’m not talking about how many races we might win. Our childhood is fundamental. So much can be done right, and so much can be done wrong.”

Vettel never expected to be an F1 driver. He was contemplating university after he got his high-school degree. It was the normal thing to do. “I finished my A levels and literally two weeks later got the phone call: You are our reserve driver; we need you at the race,” he says. “I was shocked.” He got a development seat with BMW and built his legacy, one turn at a time.

Now? He is not old. By the standards of Formula 1 set by guys like Kimi Räikkönen, who retired at age 42, and Michael Schumacher, who finished his last race when he was 43, Vettel could have another decade in F1 if he wants. Where the younger guys are even smaller, spindly from the shoulder down, conditioned to perfection, Vettel’s form is more functional, with burly forearms, a stout neck, and just a hint of padding over the six-pack. He doesn’t obsess over conditioning the way the younger guys do. He’s comfortable with his body.

You will never know where Vettel is on race weekends. He usually doesn’t stay in the fancy hotels with the other drivers. He prefers to rent a house far from the track, often accompanied by his family. He doesn’t have a business manager and negotiated his own contracts. He bridles against authority. More than most, he does things his own way.

There was no particular moment when Vettel decided to care about the climate crisis or even use the word “crisis.” But it formed in the midst of his career, race by race.

“I think I’ve always seen things,” he says. “I remember in Malaysia, where, the year before when we raced there, there was forest, and the year after, we went past and it was all palm trees. . . . For sure, I look back at some things now, and I wonder, why did I not maybe put one and one together earlier? Or why did I do certain things like flying around the world, like using private jets? This is stuff you have to decide for yourself now.”

Vettel will talk about almost anything. He doesn’t keep secrets, refuses to conceal his beliefs, and is openly emotional—much more than you’d expect from a German man, at least. Though he is beholden to a patchwork of sponsors that pay him and Aston Martin millions of dollars, there is no effort to protect them from his opinions. Boy, does he have opinions. And he always backs them up with facts.

For much of his F1 career, the Vettel haters around the world were legion. They hated him because he drove for Red Bull, which, when it arrived on the scene, was considered a clownish host of parties in the adventure-sports world. How could they possibly compete on the same level as Ferrari or McLaren? For the naysayers, Vettel became the evil posterboy, one of Dr. Marko’s creations.

Then Vettel beat Ferrari and McLaren. It was the car, not the driver, the haters said. Like every racer on a winning streak, he complained a lot and was accused of being unsportsmanlike. (Everyone remembers the Multi 21 scandal with always-a-bridesmaid teammate Mark Webber.)

But what makes a great racing driver? This conversation’s as old as the chariot races at Circus Maximus. Is it the number of wins? Championships? Podiums? By those measurements, Vettel has few peers. He has four World Championships, tied with Alain Prost and bested only by Michael Schumacher and Lewis Hamilton (and, from the pre-F1 grand prix era, Juan Manuel Fangio.)

From a championships perspective, there are 30 lesser drivers who will remain far beneath him on the list of greats: Senna, Lauda, Clark, Alonso, Villeneuve, and on and on. (The jury is still out on Verstappen, who possesses apparently limitless ability, though his only championship came from a deeply flawed decision by a racing director who was shown the door shortly afterward.)

Vettel was at Red Bull for just six years, during which he won his championships—serious ROI for Dr. Marko, who plucked Vettel from a choir of F1 contenders young and old. Before his 150th F1 start, Vettel earned 41 wins, 73 podiums, 45 pole positions, and those four titles—stunning stats that cast a shadow over his contemporaries (in the same first 149, Lewis Hamilton, with 34 wins and two championships, comes closest; Alonso and Verstappen lag far behind). Beyond the raw stats, extraordinary work ethic, and preternatural talent, the greatest drivers integrate an uncommon set of qualities: aptitude, intuition, the most cohesive team, the deepest-pocketed sponsors, the canniest team principals. It’s a sort of witchcraft with a whiff of luck.

Championships are not “just the car,” but great cars can get you close. During his four-year title run, Vettel had the benefit of driving Adrian Newey’s aerodynamic masterpieces, the RB6, RB7, RB8, and RB9, which, among other prestidigitations, deployed a blown diffuser that the competition never countered. And yet, perhaps only a professional driver can fathom the level of unrelenting focus required to maintain that level of mastery against Lewis, Fernando, Kimi, Webber, et al. Not just anyone can sit in the fastest car and win four consecutive championships.

Consider how Vettel earned the Red Bull seat in the first place. When he showed an abnormal skill in karting, his father began budgeting closely, saving here and there to fund a modest campaign. After a development gig at BMW, Vettel worked his way into a seat at Toro Rosso, a Red Bull junior team in F1 that used the previous year’s chassis with a Ferrari engine instead of the more dominant Renault mill. At the 2008 Italian Grand Prix, in the little Toro Rosso, Vettel won from pole on a grid that included a dominant McLaren/Hamilton combination and two Ferraris that filled the front of the field. Vettel’s performance was career defining, and it secured his seat at Red Bull.

Once there, Vettel locked eyes with the engineers. He talked through the car’s every component, its every weakness and nuance. He probably knew as much about Newey’s wondrous cars as his engineers. So Vettel won over the team and quickly became its natural focus. Vettel’s teammate, Mark Webber, one of the most talented wheelmen in the world, didn’t stand a chance. The same curiosity that led Vettel to discover how a disappearing forest in Malaysia is a bad sign for the climate, or how Greta Thunberg’s Asperger’s syndrome is a sign of her honest commitment to the cause, led him to become a virtuoso in a strong car.

The rest is history: In 2010, Sebastian Vettel became the youngest driver to win an F1 World Championship, at age 23 and 133 days.

Today, as a very long retirement looms over the rest of the races this season, he has no idea what he’ll do next. But what motivates him is that the fate of the planet looms over the horizon.

“I have three children and a wife I love very much,” he says. “I’m going to be very busy. Everything you think you might be doing or want to do, I don’t know if it’s going to be satisfying. Because I don’t know any different than this. But I do think there are more important things. Eventually, I’ll find my way to those.”

You Might Also Like