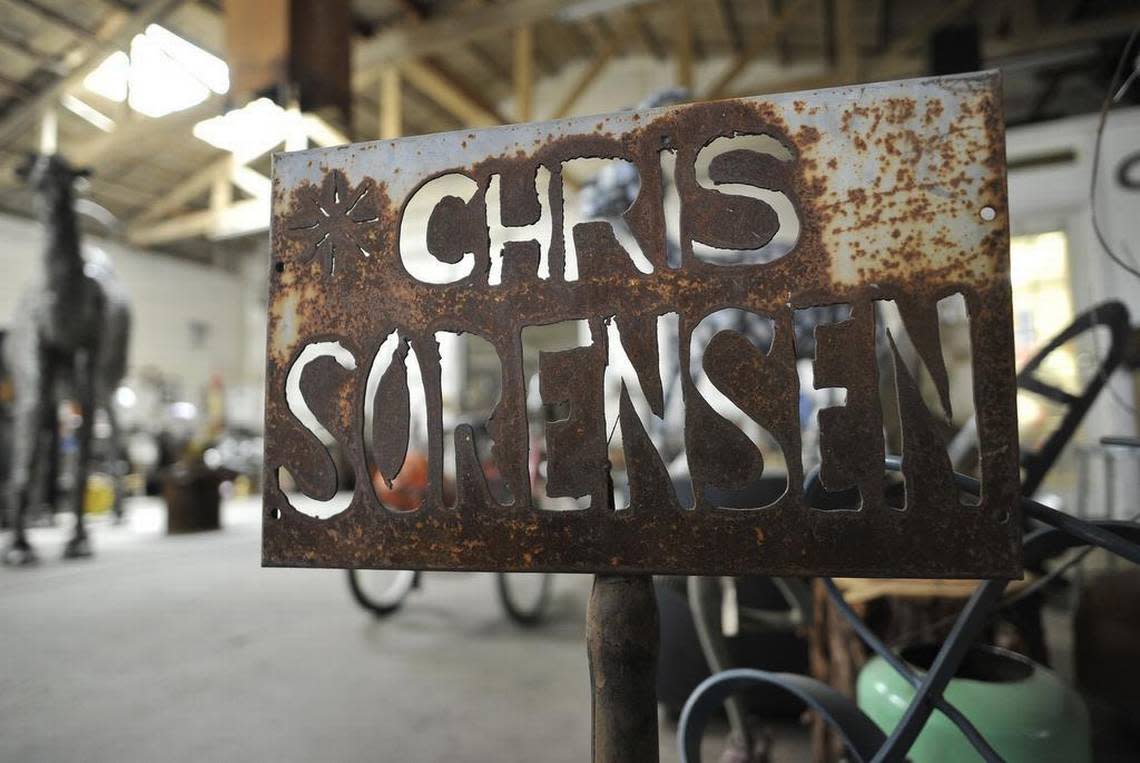

Sculptor Chris Sorensen, whose studio was a haven for Fresno artists, dies. He was 98

Chris Sorensen was the Godfather of Fresno’s arts scene and an inspiration for generations of local artists.

His work and his studio warehouse, located just south of downtown Fresno, were an instrumental part of Fresno’s arts history.

And he was still holding court at weekly arts gatherings when he died in early March at the age of 98.

For decades, the metal sculptor worked out of a graffiti-covered warehouse on south Van Ness Avenue. The studio also operated as a gathering place, playhouse and opportunity zone for other aspiring artists.

It was the original ArtHop venue and home to an annual “Nudes in November” art show, and Sorensen’s yearly birthday party, an event that was often seen as a cultural touchstone (it ranked as one of the top cultural events in 2015, as judged by The Bee’s arts reporter Donald Munro).

On Saturday, the art warehouse served as the location to celebrate Sorensen’s life. He died March 8.

‘Man of Steel’

Sorensen had the kind of story-filled life only ascribed to people who live deep into their 90s. He was the oldest of five children and grew up on the outskirts of Fresno, in Mendota, where story goes, he once slept with Amelia Earhart.

He was five years old and she was passing through Mendota and needed a place to stay, so his parents put her in his bed.

By his teen years, Sorensen had moved in the city proper and attended Fresno High, where he graduated in 1944.

After a stint in the Navy, he returned to the area — and his family’s machine works company — and eventually settled in Fresno with his wife Mitzi in 1955.

Sorensen worked as a draftsman, inventor and businessman — all before ever venturing into the arts. He even started his own welding supply company in 1963, which is still in operation.

Then later in life, Sorensen finally got into art.

It was his way to spend time with his son John, who was taking art classes in high school at the time.

Together, they learned to weld.

Sorensen’s passion for art through the use of metals soon after solidified.

Metal sculpture, especially large-scale animal pieces, became Sorensen’s signature work and earned him the nickname “man of steel.”

In 1993, for example, he created a life-sized sculpture of Nosey, Fresno Chafee Zoo’s first elephant.

The statue was based on measurements of the actual elephant, who had cancer and would die later that year.

For years, Sorensen made work just to give away or enter into the Big Fresno Fair.

At one point, he had 20 years worth of ribbons for his entries, and a single Best in Show prize, for an 4-1/2 feet tall version of Fresno State’s mascot Time Out.

By the 1990s, Sorensen’s work was being exhibited in New York and New Orleans and San Francisco, according to a story in the Fresno Bee. In 2015, a large Sorensen piece was selling for $20,000.

Sorensen was prolific.

In a 2015 interview for his 90th birthday, he estimated he’d done more than 1,000 sculptures and an equal number of paintings, because Sorensen also took art classes at Fresno City College and Fresno State and learned to paint, do ceramics and wood carving.

The Chris Sorensen Studio

Sorensen’s legacy resides in a 40,000 square-foot warehouse in an industrial part of the city, just across from the historic Fresno arch.

The building is owned by the Caglia family and for years was being leased at a discounted rate to keep it affordable for local working artists (as little as $135 a month in 2015). When increased rents pushed the artist cooperative Gallery 25 out of its space on VanNess and Mono, it relocated to Sorensen’s Studio.

Sorensen first moved into the abandoned carpenter’s shop in 1990s.

He was 65 years old at the time, had just survived a brain tumor and had handed his business over to his son.

“I wanted my own place to play,” Sorensen told The Fresno Bee.

“But I didn’t want to be selfish. I wanted others to use it, too.”

So he invited other artists to share the space. Just few at first.

Over the years, it became a haven for artistic types; the kind of place local officials would frequent when they wanted to talk to artists. Throughout the ’90s, there was a standing potluck dinner every Tuesday night attended by a group of artists, art lovers and teachers.

And even recently, Sorensen would host daily tea for those at the studio.

Keeping the space operating was a labor of love, said Debra Cooper, a metal artist who took over operations from Sorensen in August of 2022.

“He expected nothing,” Cooper said, “and gave so much.”

Often, that was monetary.

Sorensen once estimated that he put $100,000 into improving the building, and Cooper said he spent thousands each month subsidizing rents when artist couldn’t afford it.

Coming out of the pandemic, Sorensen’s health was deteriorating and he was unable to care for the studios in the way he once had. The place was on verge of closing when he reached out to Cooper to take over.

Cooper has spent the last two years working to reinvigorate the space and reintroduce it to new generation of artists and art patrons at events like ArtHop.

March’s ArtHop event, held on the night before Sorensen died, had the largest turnout the studio has seen in years.

Art at play

There are now 60 working artists who create and/or display work at the studio and gallery. It’s open Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

“It’s like Disneyland,” Cooper said.

Cooper said someone can spend a whole day at the studio and not see everything. Also, there is a magic to it that can be felt upon entering.

It’s equal parts playfulness and the love.

That was Sorensen’s whole vibe.

He often referred to his art making as play. As in, “I’m going down to the studio to play.”

And that sense of joyfulness was passed along to every artist at the studio, according to Cooper.

“That’s what Chris did,” Cooper said. “He allowed us to play as adults.”