Scientists reveal whether Earth could be saved from killer asteroid

Earth could be saved from potential deadly asteroids by smashing into them with a spacecraft, according to a new study.

In recent years, the world has increasingly looked to ensure that it has defence measures in place in case of a deadly asteroid heading towards us. While there are no known threats heading towards us for at least the next 100 years, many potentially deadly asteroids have not been catalogued and could be discovered before then.

As such, a number of organisations including Nasa have proposed possible solutions that would prevent an asteroid colliding with Earth. One of those is redirecting it or deflecting it by slamming a spacecraft into its surface.

Last year, scientists conducted the first full-scale test of such “kinetic impact technology”. That saw Nasa send a mission – named DART – towards an object known as Dimorphos, a moon around another asteroid that was chosen in part because it could be watched by ground-based telescopes.

Now researchers have revealed the results of those observations in a series of papers, published today in Nature. Among other findings, show that the redirection was a success, and that such technology “is a viable technique to potentially defend Earth if necessary”.

The spacecraft changed the orbit of Dimorphos by a large amount, which was more considerable than early estimates had suggested, the scientists found. That might be because the material that was thrown out of the object also helped add momentum to the asteroid, scientists suggested.

The test will also help guide future attempts at similar projects – which could include a really threatening asteroid. Scientists were able to gather precise information on how the DART impact changed the trajectory of the object, and hope to use that to predict the outcome of future, similar work.

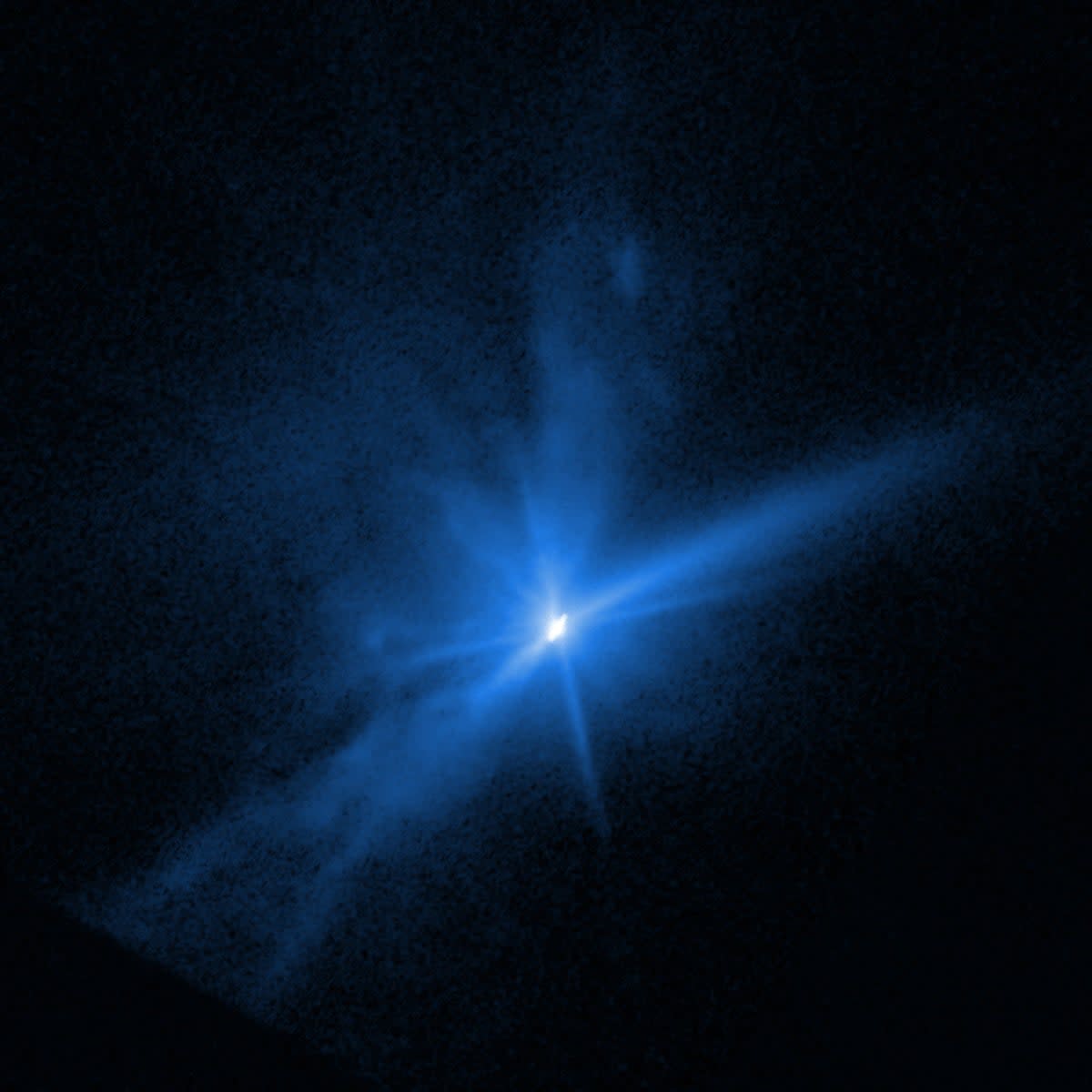

Researchers were also able to share images, taken from the Hubble Space Telescope, of the ejecta that was left behind after the collision. Researchers were able to watch that material as it spread through space in the days that followed, helping understand how the sunlight and gravity affected how it moved around in space.

As part of the set of five papers published today, researchers relied on the work of citizen scientists, who contributed observations to the work. Many of those came from consumer telescopes that people can use at home.

They were able to use the observations to better estimate the mass and energy of the dust that was ejected from the collision, which again could help plan and analyse future missions to redirect potentially deadly objects.