Schools are hiring more teachers than ever. So why aren't there enough of them?

Since the pandemic began, lots of schools have been on a hiring spree. Campuses need more classroom teachers, reading specialists, special educators and counselors as baby boomers retire and schools help students make up for lost time. The unprecedented infusion of COVID-19 relief money paid for many of these open positions.

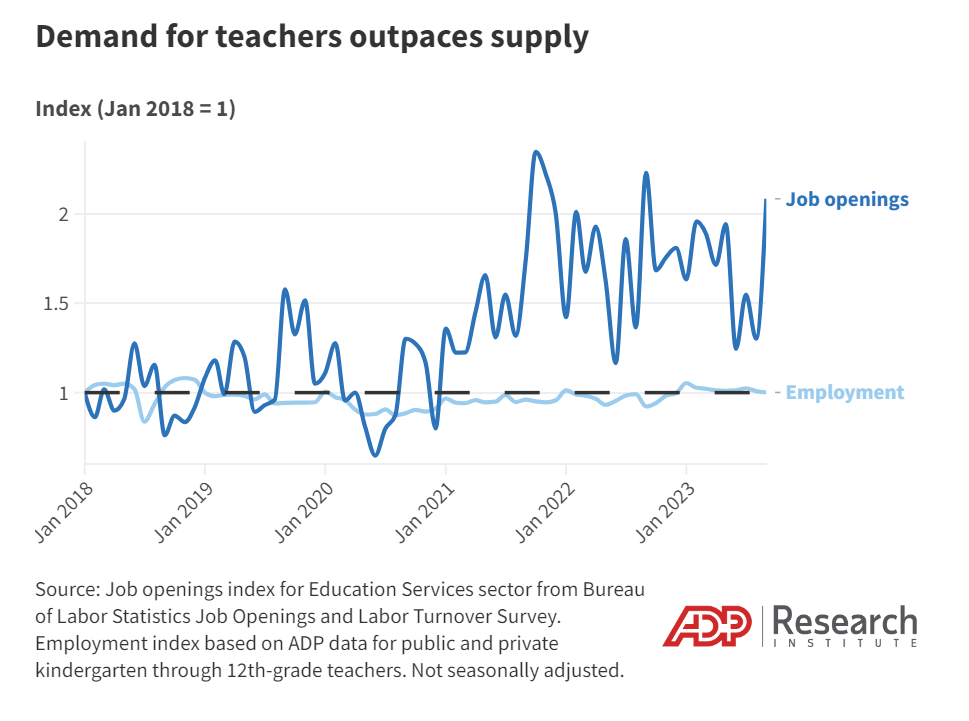

Yet the supply of applicants hasn't caught up with demand, according to a new report from ADP Research Institute, a labor market think tank. The report says there has long been a staffing imbalance, but it has become more pronounced since the pandemic.

“The demand for teachers has only grown, but the supply has been very stable,” said Nela Richardson, ADP’s chief economist. “As everybody is talking about the future of work, we’ve got to talk about the education of that future workforce – and it starts with teachers.”

The solution is clear: more competitive wages, as President Joe Biden noted in his State of the Union address last week, making the case for teacher pay raises. Despite an effort to change wages at the federal and local levels, few districts and states have meaningfully increased educator pay. Instead, teacher salaries have grown more slowly than pay for workers in other sectors.

The research institute tracked employment trends using wage and employment data over five years for public and private K-12 teachers across the U.S.

The number of educator job openings has surged since 2021, researchers say, but the number of employed educators has remained relatively flat. For a few months after the onset of the pandemic, the teaching force shrank because of resignations and retirements. Many older educators left their jobs earlier than planned, prompted, in part, by health concerns.

Teacher shortages: 86% of public schools struggle to hire educators

How teacher salaries compare

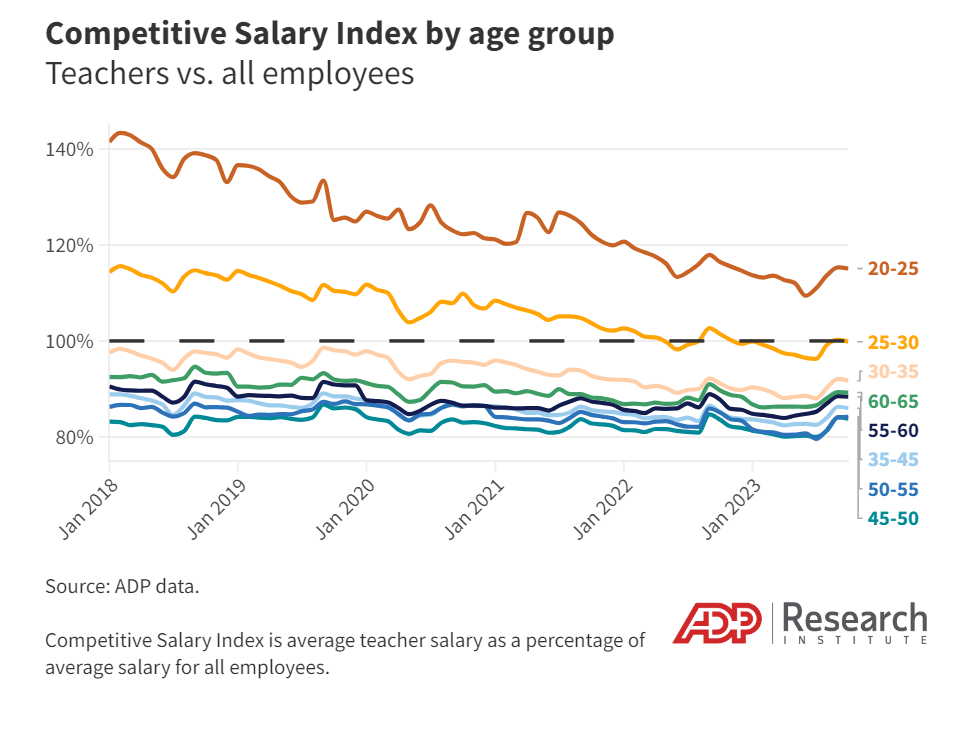

As of last fall, K-12 teachers in the U.S. earned an average $68,000 annually. That’s 8% less than the average wage for all workers in the country, according to the ADP analysis.

That gap is widening. In 2018, teachers made just 3% less than the average employee. The gap continues to widen even though teachers often have higher levels of education than other workers. That makes “the shrinking pay premium even more unsettling,” the researchers said.

That teachers are underpaid “is an old story in some sense,” Richardson said. She pointed to the wave of teacher strikes around the country starting in 2018.

But the story has gotten worse. After the mass unemployment created by the pandemic, wages in various sectors, such as hospitality and tech, soared as companies sought to recruit staff to fill vacancies. With a few exceptions, that didn’t happen in K-12 education.

Stagnating wages contribute to shortages

With school salaries struggling to be competitive, teachers are less inclined to stay on the job. They’re pursuing other careers, in education and other industries. This trend is especially evident among so-called STEM educators, specializing in science, technology, engineering and math, and those who teach foreign languages, whose skill sets can lead to more lucrative professions.

Prospective teachers are also less likely to pursue education careers in the first place. Wage competitiveness has weakened especially for teachers ages 20 to 30.

Though teachers 30 and older are accustomed to making less than the average worker, historically, early-career educators made more than other young entry-level employees. That competitive advantage has been eroding over the past few years as educators' salaries trailed downward, according to the report.

As older teachers retire, they’re vacating positions that early-career or prospective educators are not filling as swiftly. Though teacher employment trends show a consistent drop-off each June among aging teachers, these days the drop-off is happening among younger teachers, too.

“The pipeline is broken at both ends,” Richardson said.

Where teachers are being hit hardest

The report highlights two regions where educators have experienced the most significant wage changes relative to other workers.

In Florida’s Orlando-Deltona-Daytona Beach area, teachers’ salaries have experienced the biggest decline compared with other employees. Teachers went from earning 28% more than average to just 4% more over five years.

Richardson believes the region’s robust leisure and hospitality industry is a big factor. Entry-level jobs in that sector now pay more competitive wages – and those jobs require much less education and training.

American classrooms need more educators: Can virtual teachers step in to bridge the gap?

The Washington, D.C., area has seen the opposite trend in teacher salaries. The area's teacher pay premium saw some of the greatest gains: In 2018, local teachers made just 89% of what a typical worker made. Last year, they made 106% of the average.

In that case, Richardson pointed to the high local demand for private education from wealthy and international families.

But such phenomena remain a relative anomaly. “In education,” Richardson said, “that aggressive hiring and pay didn’t keep up with what other companies have been doing.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Teacher shortages are at crisis levels. Yet the pay gaps are growing