SC fails to protect injury victims while other states curbed abuse, our investigation found

If you’ve watched live television during the past decade or so, chances are you’re familiar with the name JG Wentworth.

The company’s name invokes images of vikings singing toll-free phone numbers, people shouting out windows about needing money now and an older gentleman staring into the camera, telling you, “It’s your money, use it when you need it.”

The company and others, called factoring companies, buy future payments from those who have received structured settlements and give them immediate cash. The sales are regulated by state laws and must be approved by judges.

A McClatchy investigation has found a lightly regulated industry where S.C. sellers are receiving an average of 25 cents on the dollar. And judges are almost always signing off on the deals, even when it’s questionable whether the sales are in sellers’ best interest, as required by state law.

Here’s how South Carolina is failing to protect sellers and what other states have done to fix the issues.

How do other states protect accident victims’ settlements?

Structured settlements provide long-term financial security to plaintiffs in personal injury and wrongful death lawsuits. That often comes in the form of monthly payments for decades.

“This is not something you take as a settlement option because you want to make money,” said Eric Vaughn, executive director of the National Structured Settlements Trade Association, which represents consultants, attorneys and insurance companies that help set up these financial arrangements.

“This is what you take when your biggest, most obvious concern is economic security. You want to have confidence that your bills, taking care of your family, will continue to be met for 20, 30, 40 years or more. Nothing will ever change.”

When factoring companies started purchasing future payments for lump sums during the 1990s, states began implementing consumer protection laws to ensure those deals went through a court approval process.

South Carolina is among 20 states that has essentially the same language in its structured settlement protection act from model legislation circulated in the late 1990s. Its law was implemented in 2002 and hasn’t been touched since.

Many other states have amended their laws to offer additional protections.

Even the leader of the National Association of Settlement Purchasers, which represents many of the nation’s largest factoring companies other than JG Wentworth, agreed that South Carolina’s law should be updated.

“Unfortunately in any industry involving financial services, there’s always going to be bad actors in the marketplace,” Executive Director Brian Dear said. “Our mission in (advocating for) recent legislation is to essentially make sure that we weed the bad actors out.”

One seemingly simple amendment that both the purchasers’ association and structured settlement trade organization support could close a loophole in South Carolina’s law that has led to apparent forum shopping.

McClatchy found more than 100 instances in South Carolina of factoring companies getting deals approved by judges in counties where sellers didn’t live. An attorney for a factoring company told McClatchy that he and the companies he represents believe the deals can be filed in any county because the law states that they “may” be filed in the county where the seller lives.

Florida and Virginia are among 23 states, plus Washington D.C., that have clarified in their laws that the deals “must” or “shall” be filed in the county where the seller lives.

Another popular inclusion missing from S.C. statute is disclosure of a seller’s previous transactions to the court. Illinois and Tennessee are among 15 states, plus D.C., with that provision.

Tucker Player, a Columbia-based attorney who frequently represents factoring companies, told McClatchy such a requirement would likely be unpopular among his clients, but he believed judges should know to make a “best interest” determination.

“Considering how many denials it would lead to, I doubt there’s an attorney that would volunteer that information on a regular basis,” he said, noting that he’s found judges tend to deny deals when they find a seller had already sold part of their structured settlement and didn’t spend the money wisely.

More than 63% of deals approved between 2014 and 2021 in South Carolina involved sellers who completed more than one transfer, according to McClatchy’s analysis, with sellers often being brought before different judges and to different counties.

Eight states including Alaska and Michigan require sellers to receive professional financial advice before moving forward with a transfer, and some of those states specify that consultation must be paid for by the factoring company.

South Carolina’s current law makes receiving that advice optional, and most sellers choose to waive that right, McClatchy found.

Vaughn, executive director of the structured settlement trade group, said such a provision should require the professional to be fully independent and not recommended by the factoring company.

One other notable protection, implemented solely by North Carolina, is a cap on the discount rate being offered in the deal. The discount rate is a percentage — similar to an interest rate on a loan — calculated based on the value of the future payments sold versus what the factoring company is paying for them. North Carolina’s law prevents judges from approving deals where the discount rate exceeds a certain percentage, based on a federal rate.

Critics of the factoring industry, including Vaughn, praise North Carolina’s law. But Dear cautioned that it could be limiting for a N.C. resident who needs cash for an immediate need.

What changes are recommended for South Carolina?

Susan Stauss, the National Structured Settlements Trade Association’s general counsel, pointed to Minnesota’s law as the recommended path for S.C. legislators.

Minnesota recently passed sweeping changes to its structured settlement protection act in response to an investigative series by the Star Tribune newspaper.

The series, Unsettled, which inspired McClatchy’s investigation in South Carolina, found numerous transactions were approved involving sellers with documented mental health issues, including some who were institutionalized at the time of their approvals.

Minnesota became the first in the nation to require judges to appoint an independent advisor to represent the best interests of a seller with known mental health issues. That independent advisor must be funded by the factoring company whether the deal gets approved or not, the Tribune reported.

Dear instead praised recent legislation passed in Georgia, Louisiana and Nevada that requires factoring companies to register with a specific state department to be able to conduct business.

He noted that those laws give consumers a place to go to submit complaints and prevent “bad actors” from operating in the shadows.

Hundreds of deals approved in South Carolina involved factoring companies listed under various limited liability company names, often with addresses based in Delaware, a business-friendly state that allows companies to register LLCs with minimal disclosures, McClatchy found.

Factoring companies are also increasingly being allowed in South Carolina to redact information from public court filings, a trend industry experts say is aimed at trying to prevent competitors from contacting sellers to poach the transaction.

The company registration requirements include provisions preventing factoring companies from contacting sellers involved in active transactions, though Dear emphasized that doesn’t prevent a seller from contacting other companies to seek a better deal.

How are S.C. lawmakers responding to McClatchy’s findings?

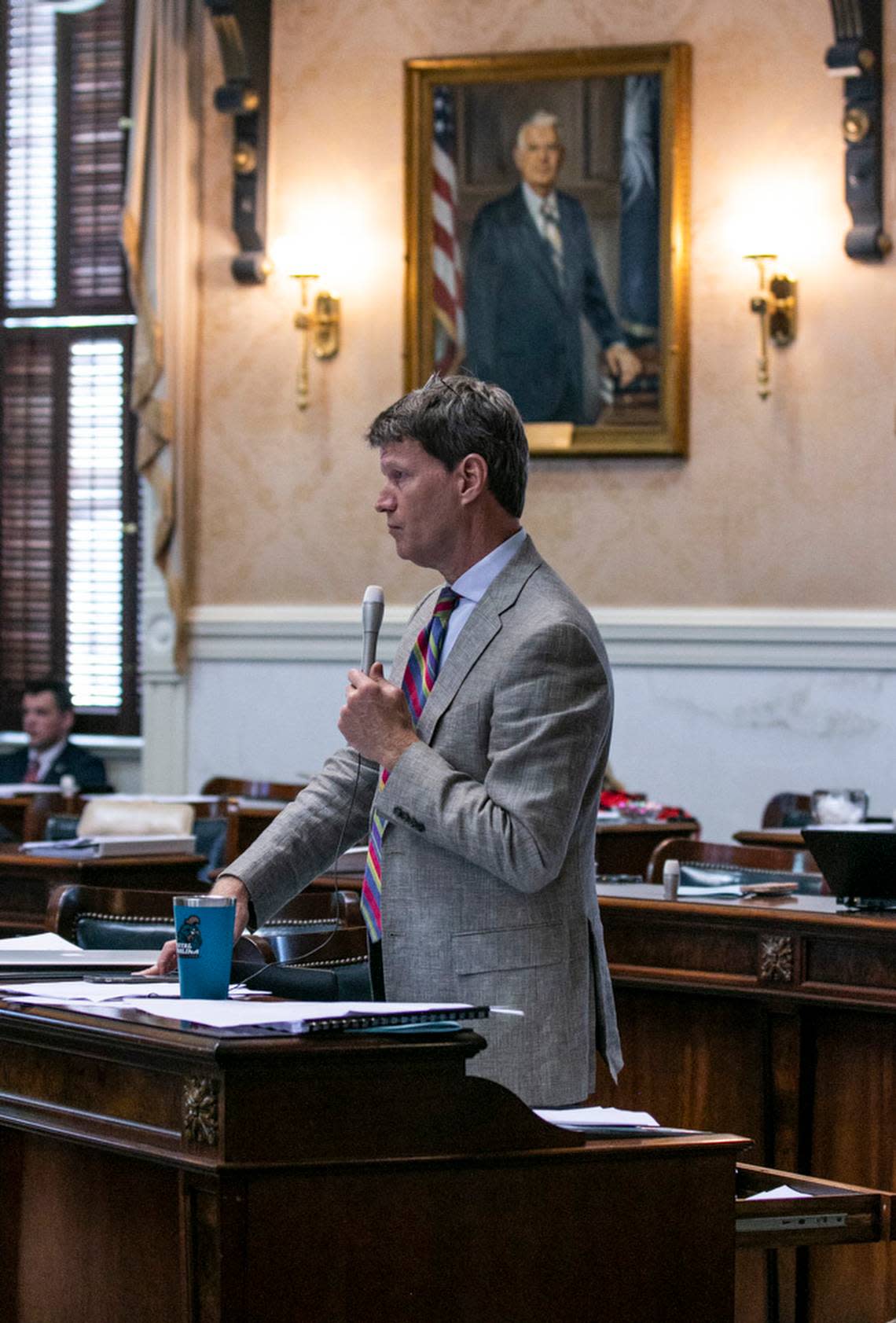

State Sen. Luke Rankin, R-Horry, expressed a desire to quickly address issues identified by McClatchy’s “Cashed Out” series when presented with the investigation’s findings.

“This is shockingly predatory and screams for reform, whether by the (S.C.) Supreme Court adopting rules and/or the General Assembly passing a law tightening requirements,” said Rankin, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the starting spot for new Senate legislation related to the protection act.

As an attorney who has previously represented personal injury clients who received structured settlements, Rankin said he has a personal connection to this issue.

“When you know the hell that they’ve been through, and the security that they get through (a structured settlement),” he said. “To see that blown up is offensive to me.”

S.C. Sen. Brad Hutto, D-Orangeburg, also an attorney serving on the committee, said he was surprised by the data McClatchy collected, which calls into question whether judges are fulling vetting the transfers.

“Maybe under our law, a full vetting is occurring, so that falls back in our court (as legislators) to change the law to make it a little more transparent and accountable,” he said.

Hutto noted that he particularly likes the idea of following the lead of other states, requiring sellers to get independent professional advice and providing judges a list of factors they must consider.

S.C. Sen. Tom Young, R-Aiken, agreed that McClatchy’s findings were “troubling.” He said he plans to work with other legislators to make improvements passed in other states.

Rankin also serves as vice chairman of the Judicial Merit Selection Committee, which vets judicial candidates to determine whether they’re qualified before being eligible for appointment.

While he said he’s never heard any questions about structured settlement transfers during his five years on the committee, he will ask questions about them in future screenings, including how frequently judges approve them and whose interests they feel more responsible to protect between the sellers and the factoring companies.

Former Island Packet staff reporter Sam Ogozalek contributed to this reporting.