The Savannah-Sierra Leone Sankofa Connection: Going Back to ‘Fetch It’

The Sankofa Bird is a mythical African bird that is pictured facing forward with its head turned backwards with an egg in its mouth. The word Sankofa comes from a Ghana language and means “to retrieve” or “go back and fetch it.”

Interpreted, it represents the idea of learning from the past and moving forward into the future. The egg signifies the youth who are our future. It is the responsibility of adults in the village to ensure youth are taught accurate truth that prepares them for a productive future. To do this, we must go back and fetch accurate truth that is too often missing or distorted in our schools.

I recently accompanied eight Savannah travelers to African nation of Sierra Leone as we endeavored to “go back and fetch” accurate truth. There is a direct cultural and linguistic connection between the local Gullah Geechee community in Savannah and the West African coastal nation. Many Africans who were captured and transported to the southern colonies of South Carolina and Georgia came by way of Bunce Island near Freetown, Sierra Leone. The purpose of our journey was to experience the connection of language and culture. In this season of thanks and giving, we went to receive Africa’s gift. We were not disappointed.

Amadu Massally coordinated our trip on the Sierra Leone end. Massally is owner of Fambul Tik, a community organization that focuses on reconnecting Sierra Leone with descendants of Africa. The words Fambul Tik mean "family tree" in English. And, Massally has made it his business to extend the Sierra Leone family tree throughout the African Diaspora.

He is especially keen on the connection between Sierra Leone and the Lowcountry. Using his expert knowledge, Massally organized our journey into three primary sections: captivity and slavery, resistance and abolition. Three of his knowledgeable employees, Alusine Kabbah, Sia Christiana Gbessengumbu, and Mohamed Jalloh were our consistent companions throughout our journey. Our visit to Bunce Island constituted the captivity and slavery aspect and was our first stop after resting from our 18-hour flight from Savannah to Freetown.

Bunce Island's British slave castle dates back to 17th century

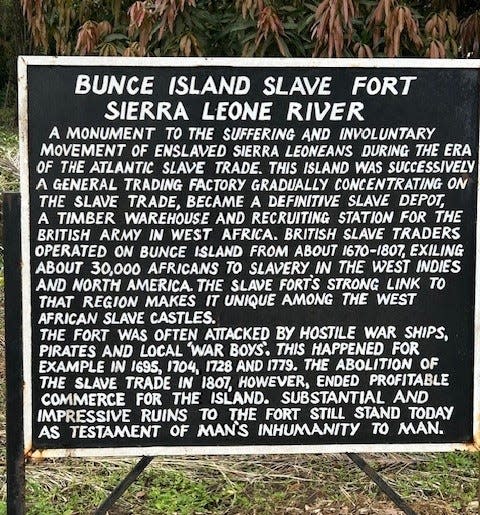

Bunce Island once housed the largest British slave castle on the Rice Coast of West Africa. English slave traders settled on the island and established the slave castle in 1670. A sign on the Island informs the reader that large numbers of captured Africans were shipped from Bunce Island to South Carolina and Georgia and that rice planters paid high prices for Africans from this region because of their skills and knowledge of rice planting. Before continuing into the depths of Bunce Island, we paused to honor the ancestors with a libation ceremony.

If you’ve attended a Gullah Geechee cultural gathering in the Lowcountry, you may have participated in a Libation ceremony where liquid (usually water) is poured into a plant as the leader recognizes the ancestors from Africa who were captured. Then, the officiant leads the audience in calling out names of Africans in America who’ve transitioned from life to death – both those we’ve only read about and those ancestral family members. The eldest in our group, Hanif Haynes, led us in the Libation Ceremony by the waters at the entryway to Bunce Island.

A unique feature of Bunce Island is that instead of having a door of no return, there was a jetty of no return. The jetty is the path on which Africans were marched down to get to small boats that would take them to the larger ships. The captured Africans knew once they reached the end of the jetty, they would never see their homeland again.

John Newton was one Englishman who made a lot of money on his numerous journeys to Bunce Island as a slave trader. It was on one such journey in 1772 that Newton experienced an epiphany and wrote a poem that became the popular Christian hymn "Amazing Grace," sung with reverence in many churches, particularly Black churches.

While standing amidst the ruins on Bunce Island, our guide led us in a chorus of that same song. Consider the multilayered irony: a white slave trader wrote the words to that song perhaps while en route between Bunce Island and the Lowcountry. That song was sung at the funeral of one the nine people slaughtered at Mother Emanuel AME Church in 2015. Mother Emanuel AME Church is the oldest AME in church in the South, established in Charleston. Two-hundred and fifty-three years later, a group of nine Savannah travelers sang a verse of this very same song while on Bunce Island. "Amazing Grace" come full circle!

Our next stop was Rogbonko Village where sweet grass baskets are sewn and sold. To get to that village required a five-hour drive down dirt roads, passing many villages. Some villages had schools and we saw children outside for recreation. Many villages had no signs of a formal educational institution. Such was the case with Rogbonko Village.

We were greeted with music, song and dance by the villagers – young and elderly. We danced and sang with them as we were led to a section of the village that had been prepared for us to engage in bartering for sweetgrass products.

Village Chief Moriai Kamara took time to meet and greet us. We were thankful that our Fambul Tik companions were present to interpret for us and guide us through the seemingly chaotic transaction of purchasing products from very enthusiastic sellers. As we were leaving, the absence of a formal educational building was noted and we discussed the academic void that would rob children of becoming doctors, lawyers, teachers, etc. As I contemplated that, however, I had to admire the fact that the villagers had successfully maintained a simple lifestyle that had been passed down for generations.

There was no gun violence, no need to participate in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program and summarize crimes into Part I and Part II categories. The children may not graduate with degrees in medicine, art or theater. However, they will develop the competency of healing with nature’s offerings, the art of creating beautiful crafts, and the skill of making musical instruments and music for the soul. They will be nurtured and trained within the safety of their community. These factors may seem minute and meaningless to us; however, these skills and practices have served to sustain people in that village for hundreds of years.

Resistance, a river that has never run dry

The trek to Old Yagala represented the resistance element. Stories are told of the Stono Rebellion and Demark Veasy’s Revolt. Articles have been written about Bear Creek Maroon near Savannah and other maroons—particularly in the Caribbean. Very little attention has been given to acts of resistance on the African continent.

The mountain of Old Yagala is near the Village of Kabala. To get there, we again passed many, many villages. One village was called Tyler Perry Town. I noticed that almost all dwellings had a porch – from the large home with obvious amenities to the small thatched hut with cut out window space. The concept of porches is from Africa. Africans are communal people and the front porch serves as a gathering place for the community.

Making the journey to Old Yagala requires “blessings” from two chiefs. We first visited Paramount Chief Gbawura Mansaray III, of Wara Wara Yagala Chiefdom. He performed a Kola Ceremony, wishing us peace and unity and a safe journey up the Mountain (at the time we had no appreciation for the significance of his prayers for a successful journey up and down the mountain). The second chief we visited was the Town Chief of Yagala Village, Chief Pa Korioi Marah. Only the elders of our group ― Gilbert Walker, Hayes, and me ― were required to meet with him.

Two griots (oral keepers of history) accompanied us up the mountain. They ran with ease. We struggled with every step and were thankful for the children who went with us as guides, pulling and pushing us until we reached the plateau. Along the way we passed a stream that served as the water source for the ancestors who lived on the mountain. We learned that this water source has never run dry.

The griots took us to the burial spot for the five chiefs and explained the necessity of a unique burial process due to the inability to dig deep graves on granite. When a chief would die, his body was hung on a hammock over a dugout pit where it would remain until his successor died. Then his bones were buried, and the body of the next chief was hung on the hammock and remained until the third chief died. This process continued through five chiefs. Being on top of that mountain – in that sacred space was an indescribable experience.

Freetown established by freed enslaved people who relocated to West Africa after the American Revolution

Back in Freetown, we were introduced to the last segment of our educational journey, abolition. The area of Freetown was established by freed enslaved people who had joined British forces during the American Revolutionary War (1765-1791). In 1787, 4,000 Black Loyalists, assisted by British abolitionists, left Canada because the British did not make good on many of their promises. They relocated to West Africa to form the Province of Freedom, Sierra Leone. Five years later, in 1792, another 1,192 Black Loyalists relocated to Sierra Leone and the capital was renamed Freetown. When they left for Africa, they retained aspects of ‘Africanisms’ from the Gullah Geechee culture they came from and took this culture with them. The descendants of Black Loyalists are the Sierra Leone Creole people.

Around 1800, about 500-600 Jamaican Maroons arrived in Freetown to join the existing freed Blacks. In 1808 Britain abolished slavery. Once this happened, many slave voyages were intercepted by the British Navy along the African Coast and the captured Africans were taken to Sierra Leone, which interestingly, became the first British colony in Africa the same year, 1808.

On a circle in the middle of Freetown stands a tall, magnificent symbol of freedom – the Cotton Tree. This tree is a kapok tree and is a historic symbol of Freetown. Reportedly, the Cotton Tree gained significance in 1792 when the formerly enslaved Black Loyalists who settled in Freetown gathered to pray under it. The tree is the oldest of its kind and remains one of Sierra Leone’s most famous landmarks. We paused once again to honor the ancestors with Libation, led by Hanif Haynes, under that tree.

Music was a universal connector in every village we stopped at. We danced, sang, and enjoyed the music played on various instruments. It was only fitting, then, that before our journey ended, we’d meet a major contributor to music/art/theatre: Charlie Haffner, founder of the 33-year old performance group, the Freetown Players.

After five action-packed days in Sierra Leone, we began our journey back to Savannah. We tasted Mother Africa and were filled from the knowledge we learned, the experiences we engaged in, and the friends we made. We returned different – we have a clearer perspective of our respective roles and responsibilities. We went to Sierra Leone to fetch the gift of accurate knowledge and truth. We returned ready to share, enriched by our experience and emboldened from the knowledge we gained. We received Africa’s gift and our Sankofa journey is complete – for now, until next time.

Maxine L. Bryant, Ph.D., is a contributing lifestyles columnist. She is an assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology; director, Center for Africana Studies, and director, Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Center at Georgia Southern University, Armstrong Campus. Contact her at 912-344-1248 or email dr.maxinebryant@gmail.com. See more columns by her at SavannahNow.com/lifestyle/.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Georgia Southern professor chronicles journey to Sierra Leone