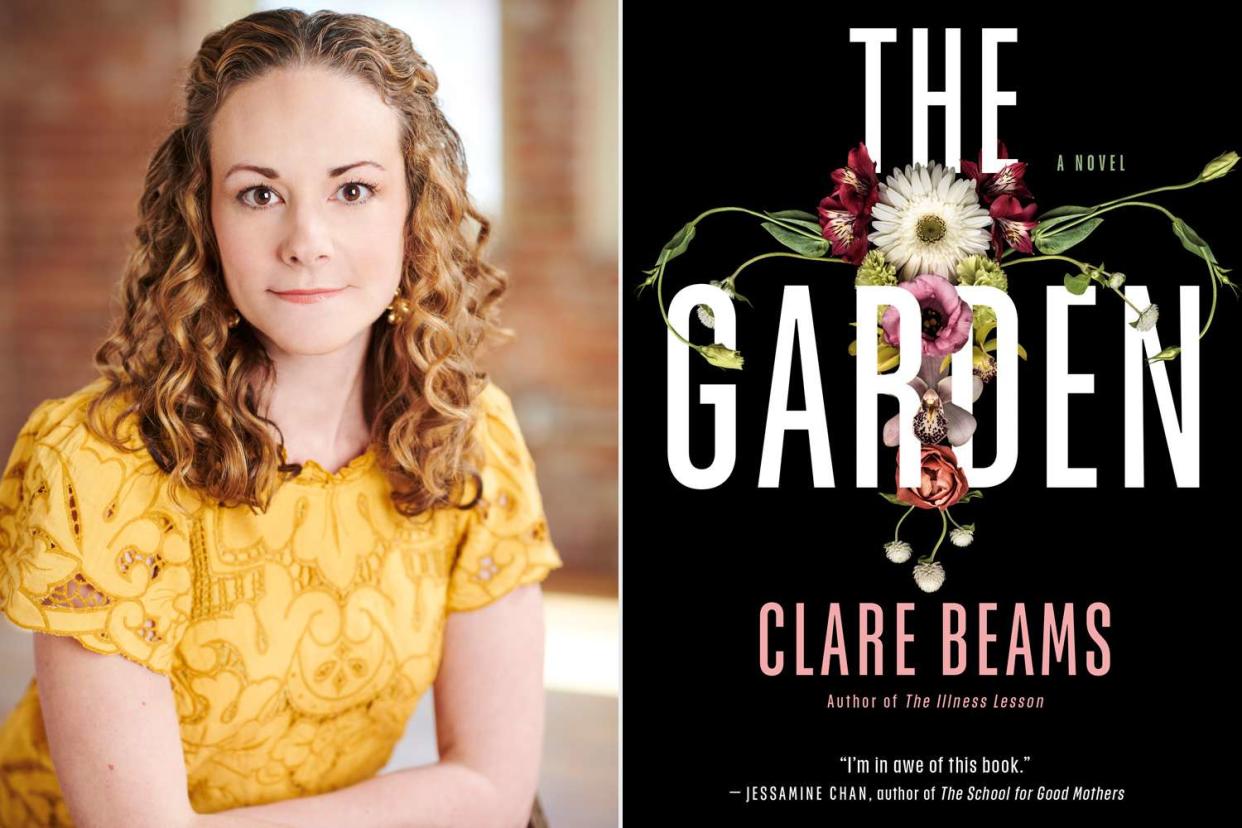

Sandy Hook and Its Ghosts: Author Clare Beams Reflects on Growing up in Newtown, Conn.

As her new gothic horror novel 'The Garden' hits shelves, the author reflects on growing up with ghosts

Kristi Jan Hoover; Penguin Random House

Clare Beams and her new book 'The Garden'It’s the summer of 1989, and I’m six years old, about to turn seven. My family has just moved to Newtown, Conn. I’m standing on the dirt floor of the basement of our new home, a rambly farmhouse/former inn built in 1735. I twirl a little on that dark, hard-packed soil, because I can see that I’m going to grow up with ghosts, and I’m the kind of kid who would have gone looking for them anyway.

This will be my house and my town, dreamy, layered with history, and mostly unnoticed by the outside world, until I graduate from high school in 2000. I will have long-since moved away and in the process of starting my own family in 2012, when the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting will happen here and turn the eyes of the world toward this place.

But of course I don’t know any of that yet. In this moment, I just know I’ve never seen anything like this room—this space. Down here in the basement, I can feel all the years. I can smell them. I’m standing on the same dirt where the house’s builders stood while they carved this foundation out of this rocky soil and left it this way, a hole in the ground. The space is large, low, and dimly lit. The supports for the house are ancient tree trunks that stand at intervals throughout, like a strange branchless forest. It’s a fairytale kind of setting that will serve as the backdrop for my childhood—the basement and the house and the whole town.

Newtown is a town of about 27,000 people, 78 miles from New York City, just far enough to be outside of reasonable commuting distance and on the rural side of suburban. The land on which it was incorporated in 1711, after having been “purchased” (stolen, really) from the Pohtatuck Native Americans, became home to a desperate little cluster of not-too-prosperous farms. During the Revolution, Newtown was a Tory stronghold, and the myth is that soldiers used the gold rooster on the steeple of the Meetinghouse for target practice when they came through as part of that war. Whatever their provenance, the bullet holes aren’t mythical: you can still see them.

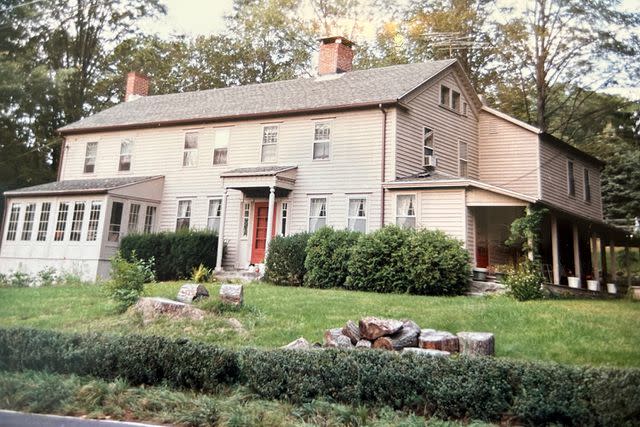

Courtesy of Clare Beams

The author when she lived in Newtown, Conn.The house I grew up in was already standing then. It hodgepodged out around a central chimney, which had an old brick bread oven we used for storing our piano sheet music, into which our cat crawled to hide when she was dying. The wide floorboards of that oldest part of the house had knotholes you could peer through—which I did, hoping to catch sight of the family from The Littles or The Borrowers. using tiny dolls when reality failed me, which sometimes I dropped and couldn’t reach. A couple of them may still be there, between that house’s floorboards. I spent hours knocking on walls in search of secret passageways. I wanted to find all the treasures its many prior inhabitants had left for me.

Newtown felt haunted, too. At the very center, there’s a green called Ram Pasture, where the colonial townspeople grazed their sheep, which stands empty because it always has. You can skate on the pond and imagine you’re in any of the last 300 years.

Different neighborhoods around that central one hold different ghosts. Hattertown was the center of the Newtown’s hatmaking industry in the 19th century, and—because a main ingredient of the bath used to stiffen the pelts was mercury—the center of its hatters’ disease. Poverty Hollow was a debtors’ work farm and is now, because time has a sense of humor, the site of some of the town’s most McMansion-y developments.

And then there’s the house on Newfield Lane in which a murder occurred that later provided the inspiration for a memorable episode in the movie Fargo: an airline pilot murdered his stewardess wife inside in 1986 and fed her body through the woodchipper in the garage, counting on avoiding a conviction if there wasn’t a body to be found.

There is also, of course, the neighborhood of Sandy Hook—still 14 years from its terrible fame when, in 1996, I began attending Newtown High School there. We haunted that school with our own lives, our own anxious energy. Our conversation inside its halls was often about our boredom: how quiet our town was, how so much of Newtown seemed to belong to the past, how it felt like a place in which everything had already stopped happening. How we couldn’t wait to leave.

During my junior year, the Columbine shooting took place, far away. I remember the teachers suddenly treating kids in trenchcoats and goth makeup with suspicion, but otherwise life continued. It was, we thought, nothing that could ever happen where we lived.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Many of us did leave, eventually. I graduated and went away to college and never lived long-term in Newtown again. My parents moved to neighboring Brookfield after my brother graduated from high school, and they retired to New Hampshire in 2010. We always drive right by Newtown on our way back east to visit family, and sometimes we stop there for gas or to drive down Main Street. Being there fills me with a strange mix of disorientation and deep familiarity, because there are ways in which I never left, in which the town still haunts me.

Related: Sandy Hook Mom Pays Tribute to Her Late Son on Dreaded Day He's Been Gone Longer Than He Was Alive

This was true before the shooting of 2012, though since then, the haunting has a new layer. I was pregnant with my first daughter on the day of that horror, watching that parade of children’s faces scroll across my screen. All of them were the age I was when I moved to Newtown—six, seven. My oldest daughter is 11 now, and her younger sister just turned seven. That age, 7, has taken on an echo. But then to some extent, all of childhood has.

Penguin Random House

Beams' new book, 'The Garden'I think sometimes about the dreaminess I learned in Newtown, the attunement to events from other times. How it felt, there, like my own moment was just a container for events that had already happened, but how it would turn out so much was still lying in wait in the future, where I couldn’t sense it at all.

How I had no idea about ghosts yet, not really It feels now, when I look back on my childhood in that quiet town whose name itself would become a shorthand for a tragedy, like I’m watching my past self through all the layers of knowledge that I have and that she doesn’t, knowledge that fear and grief are possible on a scale she hasn’t glimpsed. Knowing this, watching her—it makes me feel like each of these selves is haunting the other.

Clare Beams' new novel, The Garden, is out April 9, wherever books are sold.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.