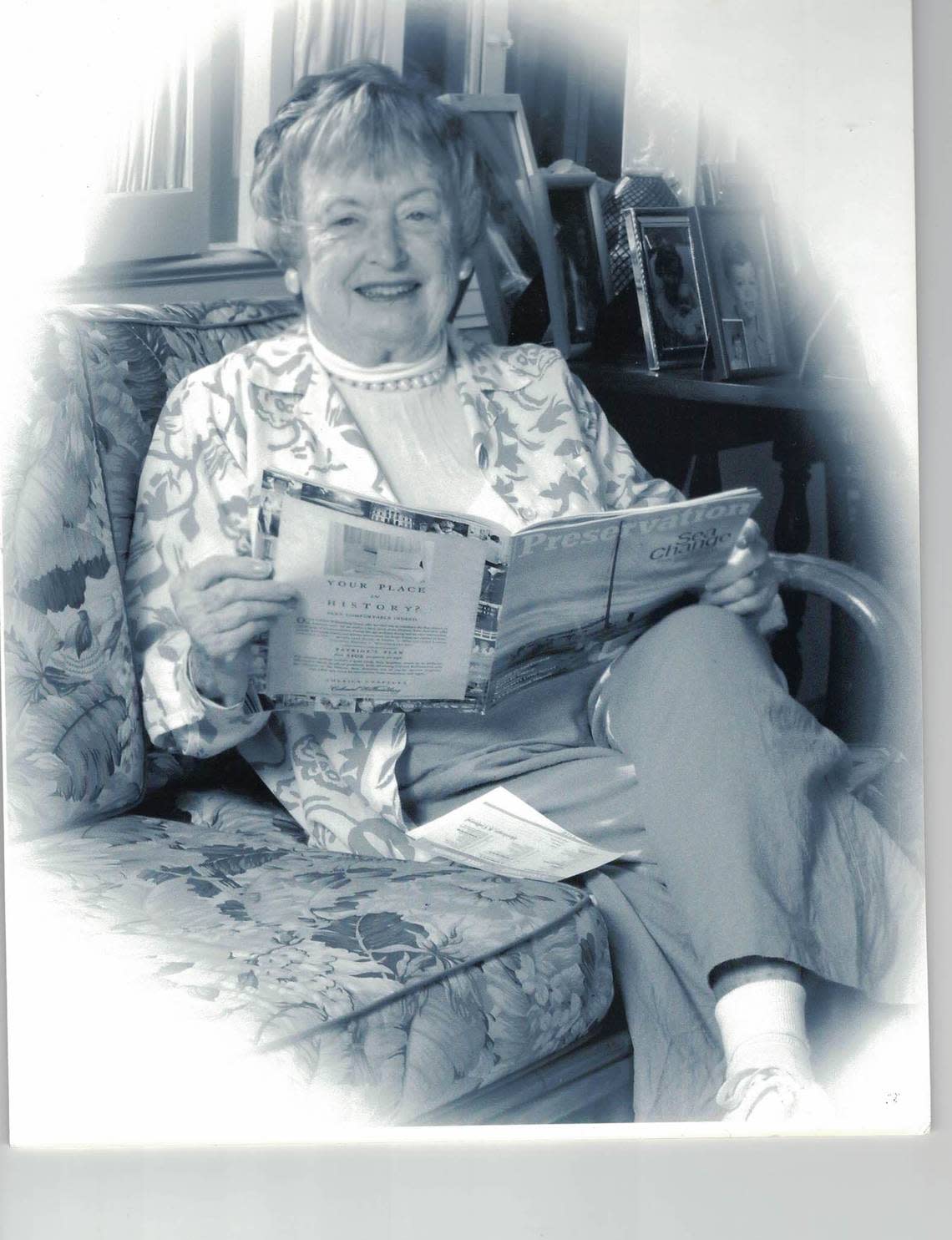

Sallye Jude, who fought to save Miami-Dade history, environment for decades, dies at 96

Sallye Jude, a transplant from Maryland who made it her life’s mission to preserve Miami-Dade County’s endangered architectural treasures and natural landscapes, has died at 96.

Jude, a Coral Gables resident for nearly 60 years and a pivotal figure in the local and state historic preservation movement for almost as long, died Friday at Jackson Memorial Hospital from an aneurysm, family members said.

Friends and allies credit her formidable tenacity in the face of what were often long odds for helping save significant and imperiled Miami landmarks that include the Coconut Grove cottage of environmentalist and author Marjory Stoneman Douglas, known as the “grand dame” of Everglades National Park, and the Miami River Inn, a collection of wood-frame boarding homes dating to early 1900s that Jude bought, restored and ran for a quarter-century as a bed and breakfast.

Persistent to the end, Jude had in recent weeks lent her name to a quixotic campaign to save a historic church garden in Coral Gables, the Garden of Our Lord, purchased by a developer for a condominium project.

She collapsed Thursday night at home after delivering and sharing cookies she made and a catered barbecue dinner, shipped from Kansas City, with son Peter Jude and his family, he said. Good friend Dolly McIntyre, her neighbor in the Gables’ historic Normandy French Village, said the strong-willed Jude tried to get into the stretcher by herself when paramedics came to take her to the hospital.

“There is no question that she was, I don’t want to say stubborn, but consistent,” said MacIntyre, a close collaborator with Jude in numerous preservation battles and endeavors. “When she got her teeth into a bone, she wasn’t going to let go.“

Jude was a founding member of Dade Heritage Trust, the county’s largest preservation group, which MacIntyre helped launch in 1972, and served as its president. One of Dade Heritage’s first moves was to restore the 1905 wood-frame bungalow that served as the clinic of Dr. James Jackson, after whom Jackson Memorial is named, for use as its offices. Jude was later instrumental in the creation of the Florida Trust for Historic Preservation, where she was also president.

Christine Rupp, executive director of Dade Heritage Trust, which still leases the Jackson office in Brickell from the city of Miami, said she often turned to Jude for advice and counsel.

“Even at 96, she always kept up with everything that was happening preservation-wise in Miami,” Rupp said. “She was tenacious. When Sallye had something on her radar, she gave it her all.”

SETTLED IN MIAMI-DADE IN 1964

Jude arrived with her family in Miami-Dade in 1964, when the national historic preservation movement was just getting started after the demolition of Penn Station in New York. It was also a time when many thought there was little history to preserve in Miami.

From the moment she settled in, though, Jude learned how much of value there in fact was in the local architecture and environment.

She and her husband, Dr. James Jude, who helped develop CPR, bought a sprawling, historic 1936 estate on the Coral Gables Waterway, Java Head, that combines elements of Art Deco, Moderne and Indonesian architecture amid three acres of gardens. The couple maintained the property for 49 years. He died at 87 in July 2015.

Sallye visited nearby Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and traveled with horticultural groups to learn how to replenish the gardens with plants and trees that would thrive in South Florida’s subtropical climate, according to a 2021 article in Coral Gables magazine.

Coincidentally, the first place in Miami-Dade that Sallye Jude worked to preserve, and the last — Java Head and the Garden of the Lord — were both designed by the same prominent Miami architect, Robert Fitch Smith.

Jude’s interest in landscapes and gardens, which motivated her to get closely involved in local plant and tree societies and took her on collecting trips around the world, led her to embrace environmental conservation and sustainable living, daughter Cecilia Prahl said.

She would unabashedly buttonhole friends and supporters about the need to preserve the Everglades, as well as on not using paper or foam plates or disposable utensils and containers, Prahl said.

“Plastic and foam were her bugaboos,” Prahl said. “She really was a force of nature. She was very strong in her opinions, and she told you about how she felt.”

Jude was born in 1926 in Baltimore, Maryland, and earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Maryland and a master’s in education at the University of Minnesota, where she met her husband, then a medical student. She worked as a teacher in Baltimore to support her husband and a growing family, while he did his medical training and pioneered the use of CPR . They moved to Coral Gables when he was recruited to join Jackson Memorial and the University of Miami medical school faculty.

Devoted Catholic mentor

Preservation and conservation were not Jude’s only preoccupations.

She was a devout Catholic and devoted Catholic mentor, and attended daily morning Mass at St. Augustine Catholic Church, always sitting in the same front-row pew. She was actively involved in local Catholic charities and, with her husband, also contributed substantial volunteer time and financial support to Miami’s St. John Vianney College seminary and the Serra Club, a lay group that promotes religious vocations for the priesthood. Son Peter Jude, drafted by his mother, now leads the group.

“She was a wonderful woman, active in her church to the very end,” Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski said. “She had a lot of boys. None of them became priests, but through her and her husband’s support of the seminary, she had a lot more boys that did become priests.

“This is a family of some consequence here in South Florida. It’s the passing of an age.”

At Java Head, she and her husband raised seven children, all but two of them boys. Sallye Jude was a stern but loving mom who kept her kids active and involved, and served as inspiration to them and their community, son Bob Jude said.

“A lot of what she liked, I ended up doing,” said Bob Jude, who runs a house painting and restoration business. “She was quite a mom. Whatever she wanted done, you did it the way she wanted. It was in a kind way. She gave us a work ethic, respect for other people, for the environment and the preservation of older buildings.”

And though their home was grand, there was little coddling and no airs — literally so at first.

“We didn’t have AC there until the early 1980s,” her son recalled. “You just opened up the windows. It’s not like we had people waiting on us. She wasn’t that kind of a person.”

Among his proudest tasks, Jude said, has been working on restoration and maintenance at the Charles Deering Estate, a historic county-owned site in South Miami-Dade where his mother served as a trustee. She was closely involved in rebuilding the estate after Hurricane Andrew caused extensive damage in 1992 and remained especially devoted to it, he said.

After James Jude died in 2015, Sallye Jude sold Java Head and moved into another historic Coral Gables house, this one in the French Normandy Village, one of the city’s seven architecturally themed enclaves.

During extensive renovations and in keeping with her environmental leanings, Jude outfitted the house with solar panels and sustainable bamboo flooring, according to the Coral Gables magazine story, which called her the city’s “patron saint of historic preservation.” She paved the patio with worn bricks salvaged from Miami’s first high school and landscaped the bare yard with plants brought from Java Head.

Over the years, Jude became close with Stoneman Douglas, who played a key role in the creation and protection of Everglades National Park, and helped oversee her care as she aged. During Hurricane Andrew, Stoneman Douglas stayed with the Judes at Java Head.

Just before Stoneman Douglas died in 1998 at age 108, Jude, through the nonprofit Land Trust of Dade County, helped raise money and led a successful negotiation with the state of Florida to buy and preserve the modest cottage that served as the famed environmentalist’s home for seven decades. Like other activists, however, Jude became vocally frustrated in recent years over the state’s inability to properly maintain the house or open it to the public as a museum, as Stoneman Douglas’ wished.

In a September interview with WLRN News, Jude said she realized she likely would not live to see that dream happen.

“Queen Elizabeth was born just a couple of days from the time I was and I know it’s not forever for me,” Jude told WLRN.

In saving and finding hew commercial uses for historic buildings that otherwise would have likely met the wrecking ball, Jude demonstrated that preservation could be good business, friends and allies say.

FIRST RESTORATION PROJECT

Her first project was the restoration and conversion of a group of wood-frame buildings in Key West into a hotel called Island City House, Prahl said. With MacIntyre and a third partner, she then bought and renovated the grand Neo-Classical Warner House from 1912 on the Miami River in Little Havana for commercial office use.

In 1984, she bought and salvaged the four wood-frame houses nearby, the city’s earliest surviving lodgings, that formed the nucleus of the Miami River Inn, as she named the property. Jude also lobbied successfully for a change in zoning rules to allow a bed and breakfast to operate on the historic property, and ran it from its opening in 1990 until 2013.

“She really put her heart and soul into this,” said developer and preservationist Avra Jain, who bought the inn in 2015, two years after Jude sold it to an intermediate owner. “If she had not preserved the Miami River Inn and done really the heavy lifting, keeping the collection of what she called the four painted ladies together in that location, that moment in time would be gone. I can’t think of anything else like it in Miami.”

Together with MacIntyre and the late Miami historian and preservationist Arva Moore Parks, Jain said, Jude not only launched the city’s preservation movement, but showed how it should be done, inspiring others like herself to do the same.

“They were the pillars of preservation in Miami,” Jain said. “There were some they wanted to preserve but lost, but thank God for the ones that they won. I can’t imagine what Miami would have looked like without them.”

In addition to children Peter, Bob and Cecilia Prahl, Jude is survived by her four other children, Roderick, John, Cecilia, Victoria Steele and Christopher, as well as 13 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Viewing will take place from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 6 at Stanfill Funeral Home, 10545 S. Dixie Highway. A funeral Mass will take place at 10 a.m. on Jan. 7 at St. Augustine Catholic Church and Student Center, 1400 Miller Road, Coral Gables.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the following organizations that Jude supported:

* Friends of the Everglades, https://www.everglades.org/donate/

* Florida Trust for Historic Preservation, https://www.floridatrust.org/donate

* Serra Club of Miami to promote and foster Catholic religious vocations, http://www.serraclubmiami.org/

Editor’s note: This article has been revised to include the dates for services for Jude which were originally omitted and to correct the name of the Land Trust of Dade County, the organization that saved the Marjory Stoneman Douglas house.