‘A safety issue’: Johnson County mom says low Kansas funding creates special ed crisis

Sara Jahnke received a call from her son’s elementary school that made her heart drop.

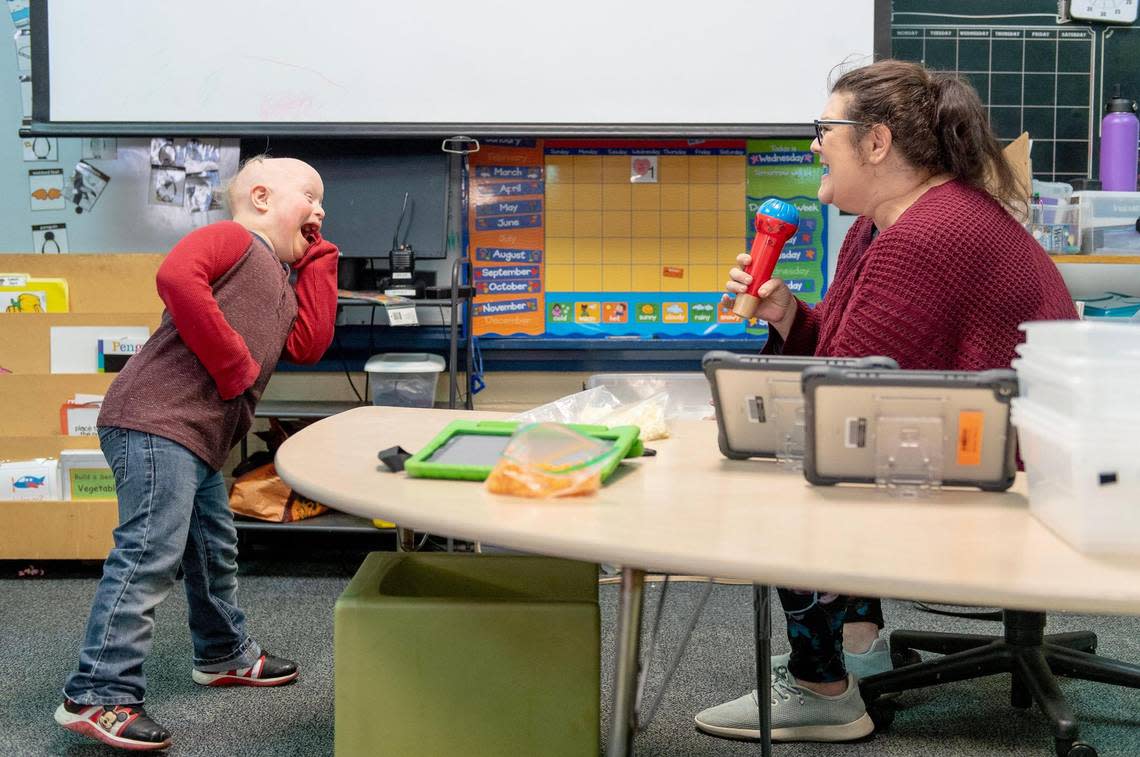

Jahnke said her 6-year-old, Crosby, had escaped his school last fall and run outside toward a busy street. The Shawnee Mission first grader, who has Down syndrome, needs to be closely monitored because he’s mastered unlocking doors and is known to run off — and when he does, he’s fast.

“They gave me a call to let me know it happened and that he was safe. Honestly, he’s a runner. And I think they were doing everything they could. But the class is just so understaffed,” Jahnke said. “He is a high-needs child. And I think that a lot of the kids that are in his class have really high needs and take a lot of attention. When you’re watching a lot of kids, it’s hard.” The district declined to confirm to The Star that it happened.

Classrooms like Crosby’s are strained this year as school districts manage record staff vacancies, coupled with a lack of resources from a decade-long underfunding of special education in Kansas. In many cases, that’s led to fewer adults in classrooms, teachers balancing more jobs than ever, unqualified staff and substitutes instructing special ed and a fear that the needs of the state’s most vulnerable students aren’t being adequately met.

“It’s at the point where it’s a safety issue,” Jahnke said.

And as schools report a growing number of special education students — along with an increase in those students’ needs — districts are pulling more money from their general education coffers to fund special ed.

As a result, all students are getting shortchanged, they argue.

“As a longtime educator and administrator, I have never witnessed the near perfect storm with the combined effects of staff shortages, increased student needs, and lack of funding. It is deeply concerning to me,” said Lee Hanson, an administrator in the De Soto district. “From my viewpoint as a director of special education services, we are getting by, but at the cost of burnout to our staff.”

Finding the funds

Educators across the state are urging the Kansas Legislature to increase special education funding to the level set by state law. To make up for millions of dollars districts say they say they should be getting from the state, school leaders pull funds from their general budgets, money they wanted to use for salaries, training, and services and instructional resources for all students.

Federal and state laws require schools to provide special education, and the federal government pays for a portion of that cost. Kansas statute requires the state to provide 92% of the extra costs. However, the state hasn’t fulfilled that obligation since at least 2011.

Gov. Laura Kelly — who made education funding a hallmark of her campaign — has called for the Legislature to infuse into special education $72 million in new dollars each year for five years to fill the gap, saying the state can afford it.

“Special education support staff are earning well below a living wage, which in turn leaves the school understaffed and under pressure,” Kelly said in her State of the State address earlier this year.

But Republican lawmakers are hesitating. Some are wary of spending more on K-12 education, which accounts for about $6.4 billion in the state’s $22 billion budget.

Top GOP lawmakers want to rewrite the state statute or reallocate existing public education dollars to special education instead of spending more.

The Senate education committee voted Thursday to remove Kelly’s requested $72 million for special ed and reconsider the item during the Legislature’s annual wrap-up session in late April.

Sen. Renee Erickson, a Wichita Republican, said it’s too early to make a decision now.

“There’s a lot of questions about funding, a lot of things being looked at,” Erickson said. “I know there are needs out there. What that looks like and how we fund that is one reason I want more eyes on this and some more time to really dig into that.”

But many educators and parents argue that delaying a funding increase, or pulling dollars out of other needed education funding, will only further harm Kansas students, whether they’re in special ed or not.

“You can make that work for a year or two, if the state is not able to fulfill its obligation on special education funding if there’s something going on with the state budget. But when that underfunding is exacerbated because it’s not been provided for a decade, you can only move the couch cushions so many times and look for that loose change,” said Leah Fliter, assistant executive director of advocacy for the Kansas Association of School Boards.

The House has approved a bill that would establish a task force to study the issue and a resolution urging the federal government to provide more money. Federal funding also has long fallen short.

“I’m fully aware that our federal partners are not pulling their fair share of this challenge,” Kelly said last week during a virtual meeting with education advocates. “I am working with other governors — I even brought this up to the president himself — that Congress, Washington, D.C., really needs to come full force and commit to fulfilling their pledge. They should be paying for 40% of the costs of special education and they’re nowhere near that.”

“But in the meantime, we still have a responsibility here.”

Though GOP lawmakers may want to wait a year and study the issue, it’s possible quicker action on some funding could be tied to another issue they hold dear. In the coming weeks, lawmakers will craft next year’s budget for K-12 schools. In recent years funding has been tied to small increases in school choice.

Republicans have introduced another wave of school choice legislation this year, to expand tax credits for donations to help students attend private schools and create education savings accounts for private school tuition.

They argue that parents deserve more opportunities to leave public districts for schools they feel better fit their needs. But Democrats contend that such proposals drain needed money from public schools, which unlike private schools are required to provide special education.

“I see that as further weakening the public school system,” Jahnke said. “It’s a detriment to kids like Crosby, and it’s a detriment to all other kids as well.”

‘Starting to crack’

Laura Robeson’s son Danny, a fifth grader with cerebral palsy and epilepsy, needs a full-time paraprofessional to help him keep up in his general ed class, plus navigate hallways and the playground, which he cannot do on his own.

During the pandemic, her son learned virtually, but since he returned to his Shawnee Mission school, she says, it has “never been fully staffed.”

“Both as a former teacher and a parent, the biggest strain is the lack of resources in terms of people,” Robeson said. “For Danny to be fully included in the classroom requires people. We need the paras, we need instructional aides, we need the people to support our teachers and our kids. It can’t be understated how valuable it is to have more expertise and people in a classroom working with kids, both with disabilities and without, to make a sufficient learning environment.”

At times, Robeson said she decided to keep her son home from school when she felt “there weren’t enough hands in the building.”

“And that is no fault of our schools. Teachers are allowed to be sick, to go to doctor’s appointments. We are all trying to take care of each other, when the responsibility lies with our Legislature allocating the money that our schools need to function properly,” Robeson said.

For years, districts have struggled to fill special education jobs, due to the strenuous certification requirements, difficult work and low pay.

In Kansas, the average starting salary for teachers is roughly $39,000, according to the National Education Association. Paraprofessionals who are uncertified but provide instructional, behavioral and other support to special ed students, on average make less than $27,000 a year.

“It is hard to attract people to a field where they can make more money working at McDonald’s,” Robeson said. “It’s a cycle we can’t get out of. Because there are fewer people, it’s harder on the people that remain. And then more people leave. It’s this impossible hamster wheel.”

Searching for staff

With districts now feeling the pain of staff shortages across the board, filling special ed jobs has only gotten harder.

This school year for the first time, schools in Wyandotte County are relying on virtual psychologists and case managers to serve special education students and their families from afar.

“Responding to the staffing shortage, I’ve really had to think outside of the box to figure out how we are going to meet the needs of our students with disabilities and exceptionalities,” said JaKyta Lawrie, executive director of the Wyandotte Comprehensive Special Education Cooperative. Such co-ops provide special education services for area member districts.

“I’ve had to make tough decisions in the best interest of our kids and to service them, but also make sure we are not overwhelming staff more than they already are.”

The Shawnee Mission district has 14 special ed teacher vacancies and 85 unfilled paraprofessional positions, spokesman David Smith said. The Kansas City, Kansas, district has filled about 88% of its special education jobs. In December, the Olathe district had nine special education teaching positions open, and 112 paraprofessional jobs available.

In the smaller De Soto district, officials said it hadn’t filled five teaching positions and 26 para jobs. In previous years, the district had zero teaching jobs open and only about five unfilled para positions.

“Ultimately, being underfunded as well as a lack of staff does impact how we serve students. But we still have to serve students,” Lawrie said. “We do all that we can to ensure the students eligible to receive services are receiving special education services.”

In many districts, the vacancies mean that lesser qualified staff are taking on those jobs.

The Kansas state education department reported 385 certified special education teaching vacancies this fall. Officials said 200 educators are teaching under a provisional license, issued to teachers still finishing a special education degree. Another 353 are teaching special ed under a waiver while they are working to qualify for that provisional license. And 237 are working on a limited special education license, which requires a bachelor’s degree and paraprofessional experience.

In Missouri, the state education department said earlier this school year that more than 600 special education teachers are inappropriately certified for their jobs.

“There is a growing frustration with parents, because we’re seeing the gaps,” Jahnke said. “This is our one chance our son has at being an elementary school student. This is our one chance at meeting these developmental milestones. If you don’t get them now, you’ll never get them. Time is of the essence.”

Said Robeson: “Because the funding isn’t there, we don’t even know what we’re missing out on at this point. We have been keeping it together with tape and shoestring for so long, we don’t even know what we’re missing.

“We are at a point now where things are starting to crack. And it’s our kids that are going to be hurt.”

‘Lose-lose situation’

Jordan House, a special education teacher at Indian Woods Middle School in Overland Park, said he’s being pulled in several directions every day.

“It’s a constant reworking of schedules to make sure our students are covered. We are trying and struggling to stay afloat,” House said. “Often we have to go to multiple classes or try and prioritize needs, which we all hate to do. It feels like a lose-lose situation.”

While teachers everywhere are dealing with heavier workloads and mounting burnout, special education has several unique challenges. Not only are they instructing large classrooms of students each with different behavioral and developmental needs, teachers say they often are forced to spend their time off filling out legal documents and writing students’ Individualized Education Programs, or IEPs.

“Special education, one could argue, is the highest burnout field because it’s so intense working with kids with disabilities. And you have to be on all the time,” said Rick Ginsberg, dean of the University of Kansas’ School of Education and Human Sciences. “Special ed has always been a high burnout field with fewer people going into it.”

In Kansas, Ginsberg said, educators must be licensed in another teaching field and receive an endorsement to get licensed to teach special education.

“You have to take a number of advanced classes, do advanced coursework, take a fairly difficult additional test, a licensing exam. It’s a lot of work and you’re not going to be paid very much to do it,” Fliter said.

In hopes of attracting more people to the field, Ginsberg said, KU started a program this past fall where undergraduate students can work toward a special education licensure degree.

Kansas City area districts have raised salaries, offered bonuses and other incentives to try to attract and retain more special education staff.

A lack of employees is becoming a larger problem, they say, because special education enrollment is growing faster than overall student enrollment.

More special ed students

The number of special education students in Kansas has increased nearly 18% over the past decade, according to the state school boards association. That comes as total student enrollment was growing slowly then began to decline around the first year of the pandemic.

In Kansas, special education students include students with disabilities as well as gifted students.

Families flock to Johnson County school systems that have a reputation for quality special education programs. In Shawnee Mission, Smith said the district serves nearly 4,000 special ed students, a number that over the past five years has grown by 360. In the past five years, the Olathe district has seen the number of special education students grow by more than 13%.

In Blue Valley, more than 18% of students receive special education services. Special ed enrollment is up 17% since 2017, while overall enrollment was down 2%, Superintendent Tonya Merrigan said.

In De Soto, the district is serving nearly 1,000 special ed students this school year, a 20% increase over five years.

The state school boards group says the number of students identified with disabilities grew because of federal and state policies, as well as more requests from parents. The state has increasingly prioritized early intervention, identifying students with developmental delays or disabilities in early childhood and providing them support from the start.

“Early intervention is absolutely what we need to do for kids. It gives them the best chance of getting caught up and succeeding,” Merrigan said.

Educators also say they’ve seen more students with emotional, behavioral and developmental needs since the pandemic.

Districts and universities have launched several programs, offering incentives to paraprofessionals and other uncertified staff to get licensed.

“We have established our second grow-your-own program,” Smith, with the Shawnee Mission district, said. “Over the last three years we have reduced caseload sizes and created opportunities for staff to work on paperwork requirements within their duty day.”

Kansas districts have had to increase special education spending by more than 31% over the past decade. That is 50% higher than the rate of inflation over the same period, the school boards group says.

But without the state or federal governments providing enough money, local districts must divert money away from general education.

“Special education is a federal mandate. So regardless of the funding situation, kids under special ed are going to get the services that are required,” Fliter said. “But the problem is that you then end up running the risk of districts having to cut back on other programs in the general education population. You can’t fund a lot of general ed programs because you have to backfill special education funding.”

‘A conscious choice’

This school year, state aid is covering about 71% of excess special education costs not funded by federal money. Local school districts have to make up nearly $160 million, the school boards group says.

District leaders say they are obligated to meet special education students’ needs at whatever cost, which could include providing full-time nurses or paraprofessionals, occupational therapy or behavioral specialists.

In Olathe, district officials said the state provided only 54% of its excess costs, so the district had to pull more than $28 million from the general budget to cover special education. That expense, along with rising special education costs, contributed to the district’s need to cut millions of dollars and several positions from its budget last year, officials said.

The Blue Valley district said it received about 62% of its excess costs from the state last year, and transferred nearly $10 million out of its general budget for special ed. And in De Soto, the district transferred $5 million.

“That means that these funds are not available for other needs, most notably staff salaries, student intervention services, training, and instructional resources,” De Soto Superintendent Frank Harwood said.

District leaders said that if they were receiving the full 92% reimbursement rate required under state law, they could free up funding to hire more staff, raise salaries to attract and keep that staff and improve general ed programs.

“Special education is so important. And when a district has to supplement funds to provide special education, it really impacts all families,” Lawrie said. “There are some students that really need help and support but don’t qualify for special education. When you take funds away from general education, you limit how you can support those kids as well.”

While the governor is pushing to fully fund special education over the next five years, some Republican lawmakers have argued that schools already are receiving more funding that could be used for special ed. After a nearly decade-long lawsuit where state courts ruled repeatedly that Kansas hadn’t constitutionally funded its schools, the Legislature channeled more money their way.

Kansas Rep. Kristey Williams, an Augusta Republican, previously floated reallocating some of that general education money to only special ed.

But educators and parents argued that will only erode public schools.

“We are recovering from about a decade of underfunding general education as well. We finally got the Legislature and court and governor to all agree on a solution in the school finance case. We just start to get that funding in place, and then COVID hits,” Fliter said. “That funding has only started to trickle in. The state has a discrete and separate obligation to also fund 92% of the statewide excess costs for special education.”

Robeson said reallocating education funding, “is just a shell game then. We’re not meeting the needs of our schools, we’re just shuffling the responsibilities.”

“I think it’s unfortunately a common experience among parents of kids with disabilities that we are used to be overlooked,” she said. “We are denying what our children need to be educated and grow up safe and supported. It’s an unfortunate choice. And it is a choice. At this point, it is a conscious choice to deny it. We have the resources, but we lack the will.”

The funding formula

Some GOP lawmakers claim that special education funding is allocated unevenly throughout the state. Williams, who chairs the K-12 budget committee, has consistently pointed to the small number of schools that receive more than the 92% threshold as evidence of a broader inequity in the state’s funding formula.

Williams said the state should study how Kansas allocates the funds before providing additional dollars.

“I think other states have simpler methods for computing and we are in a small group of states that have a complex method for computing,” Williams said earlier this year. “I’m never in favor of a complex plan and I’m never in favor of a plan that doesn’t create parity.”

On Thursday, Williams said she was still considering the best options for Kelly’s funding request. But she said the task force to address the formula and the statute itself was a top priority.

Missouri and other states use different formulas to calculate their special education funding.

Rep. Valdenia Winn, a Kansas City Democrat, said there’s been confusion over what money should and should not be considered part of the state’s statutory funding for special education. Some argue the state is reaching the 92%.

“There’s a debate going on of how we define our terms,” she said.

The state aid is distributed partly based on the number of full-time equivalent special ed teachers a district employs. Because most of the money pays for salaries, the school boards group says that hiring more or fewer teachers, or paying higher or lower salaries, can cause an individual district’s state aid to fluctuate.

She said the primary example of a district appearing to receive more than 92% is when it serves as the home for a special education co-op.

“The suggestion that we just calculate the formula differently is baffling to me, or calculate it in a way that looks favorable is baffling to me,” Jahnke said. “We need to increase funding. Either way, more money needs to go to supporting these kids. I’m disappointed that we have to have this argument. I’m disappointed that we have to fight so hard for resources that we know are needed.”

Fliter said that it “doesn’t hurt to talk about’‘ reviewing the funding formula.

But, “talking about rejiggering the formula is no excuse for not getting started on fully funding it. It shouldn’t be an either/or. These are needs that are present now, not only for special education kids but for kids in general education classrooms as well.”

Jahnke said she’s trying to remain optimistic. But in the meantime, schools are running on empty, struggling to pay staff and afford resources, like a device to help her son Crosby communicate in class.

And as the legislative session goes on, Jahnke said she’s increasingly disappointed, feeling that students like her son are not seen as a priority.

“Our kids are as valuable as other kids,” she said. “They’re just as valuable.”