Russia Damaged Another MQ-9 Reaper, Proving Drones Are ‘Easier to Deploy and Easier to Destroy’

A Russian fighter jet severely damaged an American drone in the skies over Syria earlier this month, marking the second such incident this year. The fighter released a stream of burning hot flares in the path of an unmanned MQ-9 Reaper, indicating how automatic, push-button warfare can make it easier to open fire on a target—and potentially dramatically increase the odds an armed incident could spiral out of control.

So, we asked an expert to weigh in: is drone warfare becoming too much like a video game, psychologically removing soldiers from their actions? Or is it an example of technology’s ability to reduce human casualties?

A Campaign of Harassment

The incident took place over Syria, where the MQ-9 Reaper was performing overwatch duties for U.S. troops participating in Operation Inherent Resolve. As the video above shows, the Su-35 Flanker-E fighter jet approached the unmanned drone from the rear and accelerated in front of it. Once in front of the drone, it released a stream of anti-missile flares. The hot-burning flares, designed to lure away infrared guided missiles, “severely damaged” the Reaper’s rotors. Despite the damage, the drone was able to safely land.

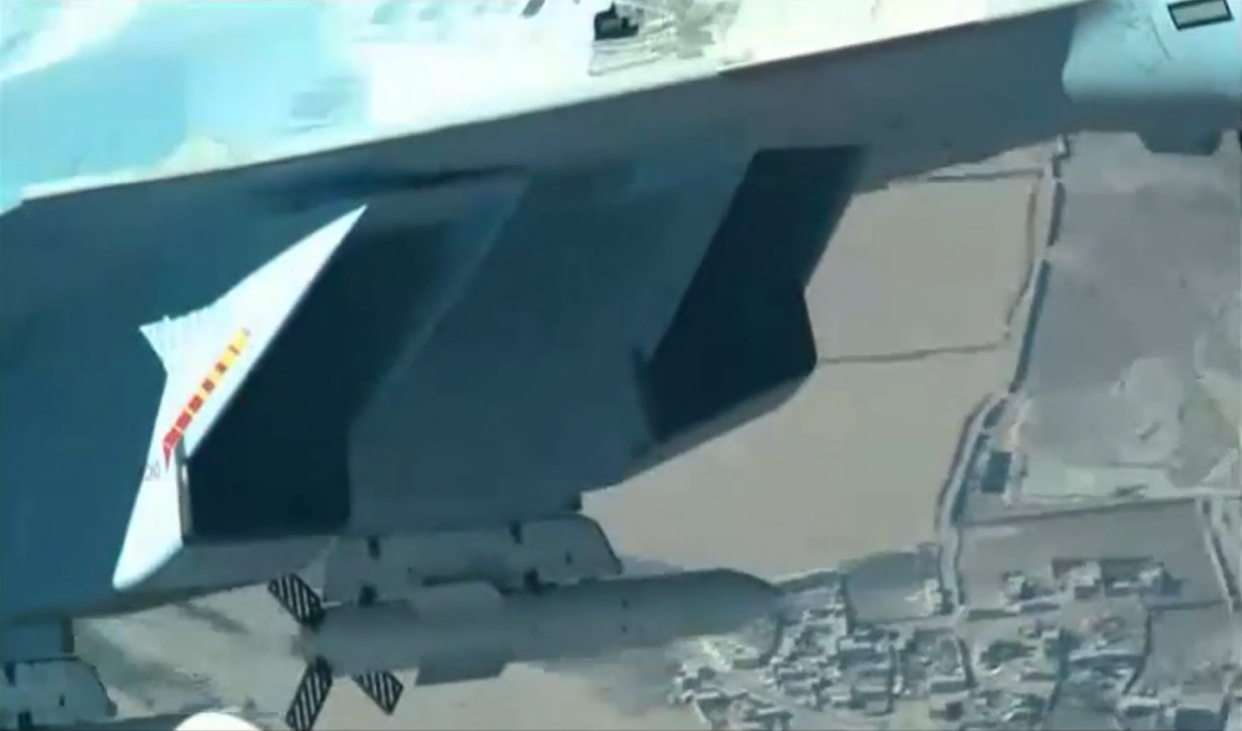

The multi-role Su-35S, Russia’s newest operational fighter jet, was also carrying a pair of Vympel NPO R-77 long-range air-to-air missiles, as shown in the video still (below). The R-77 is roughly equivalent to the American AIM-120 AMRAAM missile. The aircraft was also carrying a pair of unidentified missiles on its wingtips, locations typically reserved for the R-73 infrared guided missile. The R-73 is roughly equivalent to the American AIM-9X Sidewinder missile.

Low Escalation Risk

The Pentagon’s fleet of surveillance drones has taken a beating. In 2019, Iranian air defense shot down an RQ-4 Global Hawk drone operating in international airspace. In March 2023, a pair of Su-27 Flanker fighters flew past another MQ-9 Reaper over the Black Sea. One of the Su-27s accidentally clipped the Reaper’s propeller, damaging it to the extent it had to be intentionally crashed.

Russia is bullying U.S. drones where it can find them, and is doing so in retaliation for America supporting Ukraine. In a broader sense, however, Russia is doing it because America can shrug off the shootdown of a drone—no humans are endangered, after all.

“An MQ-9 Reaper does not have a mom or a dad. It doesn’t go to school, play video games, or prefer Domino’s to Pizza Hut. It’s a drone,” Zachary Kallenborn, a drone expert, tells Popular Mechanics. “If a state loses a drone, there is no great public outcry to rescue a lost brother or sister. So, drones are both easier to deploy and easier to destroy.”

Push-Button Warfare

In the modern world, death is dealt with the flip of a switch or the press of a button. The weapon system—be it a missile, remote-controlled gun, or drone—then opens fire on the target, eliminating it. That’s a far cry from warfare during most of human history, when killing involved cutting, smashing, or pounding the enemy with your bare hands.

Once humans started using tools, the tools became more sophisticated, and the killing became more removed from the killer. It’s easier to pull the trigger of a gun than to swing a knife, and it’s easier to press a button than it is to pull a trigger. The operators of armed drones are even more removed from the action; in Afghanistan, drones like the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper were often operated from as far away as Nevada, thousands of miles from the combat zone. But does that physical distance translate into psychological distance?

✈ Can’t Get Enough of Our Drone Coverage?

• The Secret Behind Russia’s Swarms of Deadly Drone

• Every. Single. Drone. Fighting In Russia’s War Against Ukraine

• Russia Says It’s Building Hibernating Drones That Can Sleep for Weeks Before Attacking

• Jam Buster: How Ukraine’s ‘Secret Weapon’ Shrugs Off Russian Radio Interference

• Ukraine’s Humble Cardboard Drones Are a Master Class in Stealth

• A Ukrainian Teen’s Remote-Controlled Drone Helped His Military Destroy 20 Russian Tanks

“The psychological implications of drone warfare are far from clear, and hotly contested,” Kallenborn explains. “Although various academics argue drones turn war into a video game where soldiers kill easily without connection to the lives lost, other research, particularly recent studies, show drone operators are often more connected to realities on the ground.

“Soldiers become soldiers to protect and serve,” Kallenborn continues. “Their training and experiences should, and often do, encourage them to connect with the soldiers around them. Watching your buddy from boot camp risk their life in a war zone thousands of miles away might connect drone operators more directly to the lives lost and saved—compared to, say, an artillery operator in theater who may be physically close to the action, but has no way to see the results of their shell blasting apart an enemy position.”

Remote-controlled warfare extends beyond armed drones. This summer, during the Wagner revolt against Moscow, the mercenary group emphatically stated it did not want to open fire on Russian troops manning checkpoints. There was no direct Russian-on-Russian ground fighting. Wagner troops did, however, open fire on Russian aircraft, shooting down seven helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft, killing a total of 29 air crew.

Although there was no public explanation for the aircraft shootdowns, one theory is that it’s easier to see an airplane as, well, an airplane, and decide to shoot it down, rather than consider the people inside. The decision to kill is even more removed when the airplane is a mere radar track on a computer screen.

The Takeaway

Nations can take risks with unmanned aircraft, like drones, they can’t take with manned aircraft. That cuts both ways, though, as adversaries are more likely to open fire on unmanned aerial vehicles. But, as the Wagner mutiny might show, even vehicles with humans inside can be psychologically easier to fire on if technology reduces them to targets.

You Might Also Like