Ruby Bridges: Why Kids Should Learn About My Desegregation Story

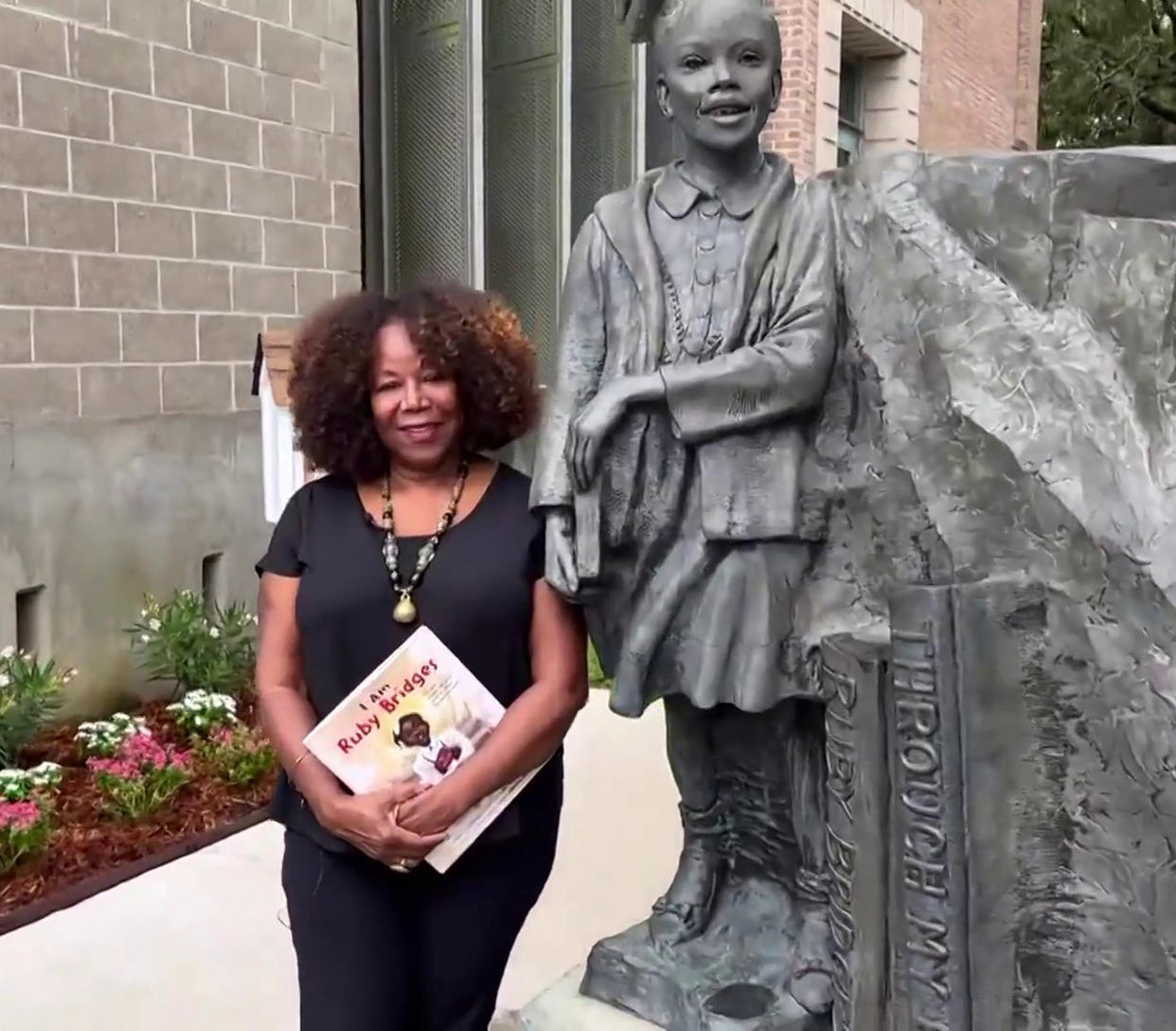

All 6-year-old Ruby Bridges wanted was a friend when she walked into William Frantz Elementary in 1960 as the first Black child to desegregate the New Orleans school, flanked by four federal marshals and besieged by racist taunts from a crowd of white people.

"I wanted a friend, it didn't matter to me what that friend looked like," Bridges told TODAY Parents on Sept. 6. "That's what drew me to school: The kids that were there, and wanting friendship."

Friends were hard to find. Bridges was isolated for that entire year: Federal marshals continued to accompany her to first grade, but white parents pulled their children out of the school and she was the only student in her classroom. Death threats against her continued, and other children in her grade refused to socialize with her.

"After being in an empty classroom for almost a year ... a little boy said to me 'I can't play with you, my mom said not to, because you're a n-----. I don't even think it was that he didn't want to play with me. At 6 years old, he was explaining to me why he couldn't: Because his mom said not to. At that moment, she had exposed him to racism. At 6, that's when I had my wake-up call," Bridges said, in an interview before appearing on the TODAY Show.

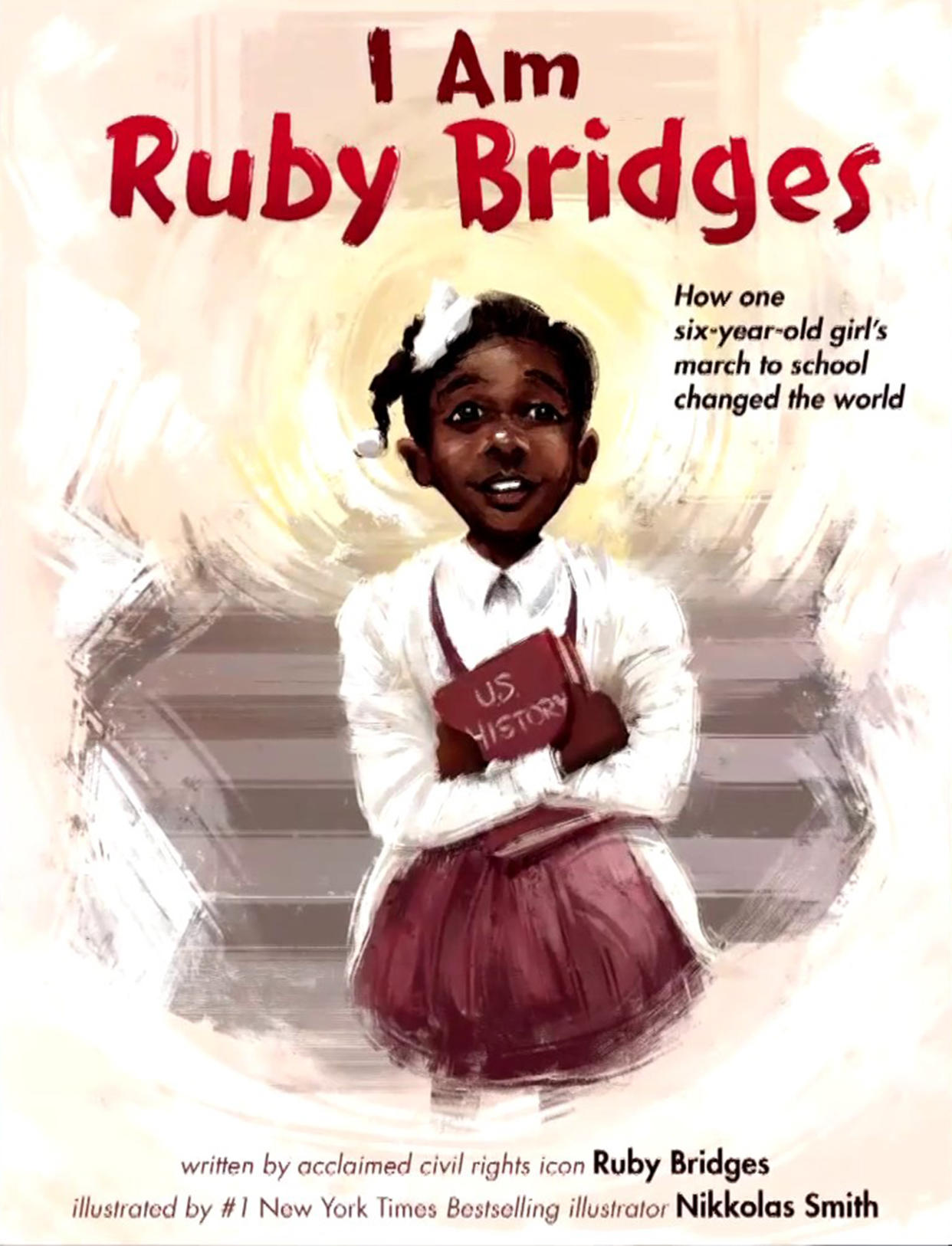

Now 67 and an outspoken civil rights activist, Bridges still advocates against racism. With her eponymous foundation and several books, including the new children's book "I Am Ruby Bridges," she wants kids to learn to be kind to each other.

"There's a message that I often leave with kids, and it's that racism has no place in the hearts and minds of our children," Bridges said. "If we're going to get past our racial differences, I believe it's going to come from our kids."

"What I find is that my story resonates with kids," she continued. "They put themselves in the shoes of this little girl, and they understand the loneliness, and they understand someone not wanting to play with them. I think they get it."

The publishing of the book comes as schools and libraries across the country grapple with legislation restricting how schools teach about racism and the civil rights movement. In some parts of the country, previous books by Bridges have been pulled from shelves because the content is "too mature" for children.

Bridges said that she thinks that the worst thing the United States can do is limit teaching about racism. Instead, she said, children should be taught to embrace the differences of others.

"The slogan of my foundation is that racism is a grown-up disease, let's stop using our kids to spread it," Bridges said. "Our babies come into the world with a very unique gift, and that is a clean heart. It's we as adults who pass things on to our kids. If we can teach them to be racist, they can be taught not to be racist."

To start that journey, she wants kids to learn about the importance of being kind to others and taking the first step to reach out.

"Someone may be lonely and need a hand, and you can extend your hand, and offer them that friendship," Bridges said. "That's the beginning, and that's what kids understand. ... They will understand someone not giving them a chance or not allowing yourself a chance to get to know someone and know each other. You're never too young to learn that."

Bridges said that she is hopeful for the future and believes that those lessons of kindness and anti-racism will prevail.

"Where do you think you would be if you were not hopeful, if you had no hope? Where would that leave us?" she said. "That's what I think about: whether we're going to see the glass half-full or half-empty. I choose to see it as half-full. I need that, and I think so would all of us, so that's why I am hopeful."

This article was originally published on TODAY.com