Rotted floors and mold: Coastal climate change hurts affordable housing residents the most

There’s no longer a trace that Audrey Hamilton’s great-granddaughter fell through the kitchen floor of her great-grandmother’s mobile home.

Or that the refrigerator the teen was trying to get to sank below the soggy presswood. Both were swallowed up after the floor had been weighed down and weakened by a leak and trapped moisture.

It wasn’t the first — or last — such incident since Hamilton moved in nearly 30 years ago.

Hamilton is one of thousands of people living in affordable housing in Beaufort County whose homes near the coast are being increasingly impacted by climate change. The residents report rotted wood, mold and flooding, which can be directly related to environmental causes.

Whether it be a mansion or a public housing unit, the effects of climate change — stronger storms, higher temperatures, more humidity and others — will impact all coastal homes. But people living in affordable housing, who struggle to find the money to upkeep their homes, are hurt more from the hazards of coastal living because of climate change, experts say.

Affordable housing is a catch-all phrase that includes housing provided by government programs such as Section 8 or public housing. It can also include manufactured homes, tiny-homes or co-living spaces. Affordable housing tenants pay no more than 30% of their gross income for housing costs, including utilities.

It’s critical, experts say, to provide safe, affordable housing, particularly in a county where home prices are high and those who need affordable housing do everything from staffing restaurants to teaching children.

Humidity and heat clash

In 1995, Hamilton left Upstate New York for Bluffton to retire to the southern heat and humidity she craved.

She found a mobile home in her budget. It was a 10-minute walk to the May River, and her church was close. For a while, the affordable slice of paradise was just that. But about a decade later, the combination of water, moisture and humidity buckled parts of the living room flooring.

“I wasn’t even finished paying for (the home), and there were holes in the floor,” Hamilton, 85, said.

She couldn’t afford the cost of the first repair. Today, she can’t afford to fix the most recent puncture, a couch leg that pierced her bedroom floor. It’s been nearly 20 years of working with The Deep Well Project – a Hilton Hilton-based nonprofit – to patch the damages caused by leaks, humidity and water damage.

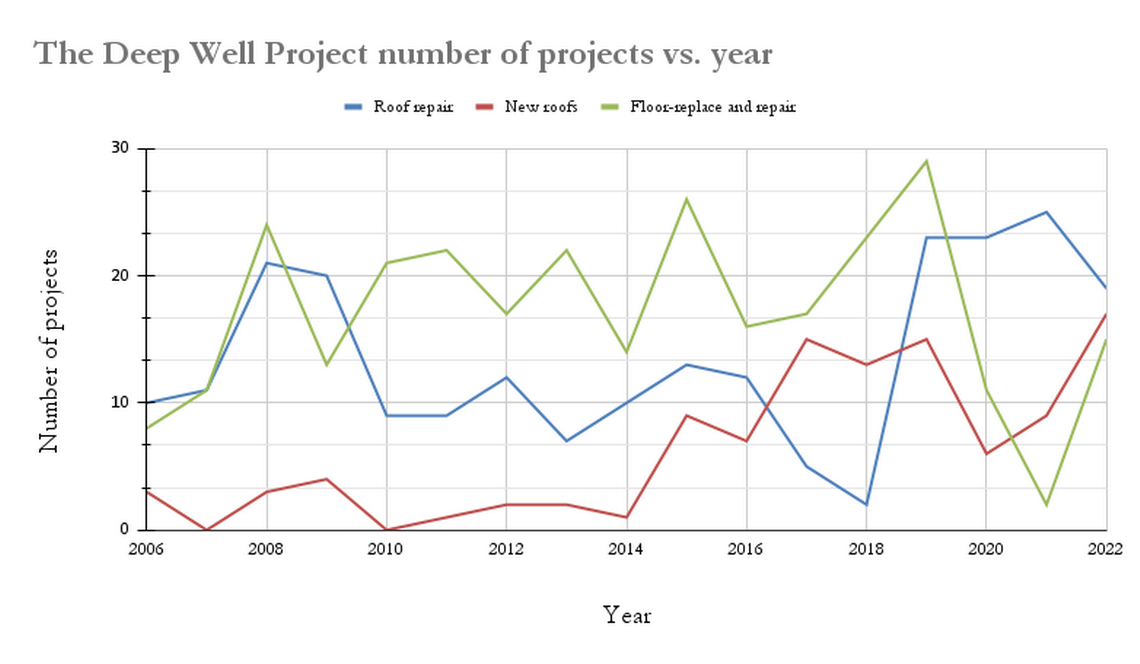

In the five years that Sandy Gillis has headed Deep Well, the nonprofit has done over 1,100 repairs for people living in Beaufort County affordable housing.

Gillis has the data to show an increasing need for floor repairs along with roof repairs and roof replacements. Fixing floors and roofs rank among the highest of the 30 types of repairs the nonprofit’s livable housing program offers to low-income residents. She says about 50% of those repairs are related to increased storm damage and the other half are needed because of leaks.

Deep Well’s data reveal a spike in roof and floor repairs beginning in 2018, which Gillis said could be related to the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew’s impact in 2016. Matthew didn’t directly cause all of the damage. But when the storm hit Beaufort County as a Category 1 hurricane, it “planted the seed,” weakening trees to the point that subsequent and lesser storms caused them to topple over.

Gillis said she anticipates that as mobile homes continue to pop up on Hilton Head because of their low cost, climate change will lead to an increasing number of environmental-related requests for repairs. She added that the existing mobile homes will also need further repairs.

“Some (mobile homes) are 20, 30, 40 years old,” she said. “(People) keep living in these houses until they fall on their heads.”

While Deep Well completed repairs to 99 homes last year, Gillis said the pending needs were overwhelming. Over 100 requests remained unfilled.

“We’re not worried about whether we’re going to do luxury vinyl or laminate flooring, we’re putting plywood down to make sure the baby doesn’t fall through the floor again,” Gillis said.

In Hamilton’s situation, her teenage great-granddaughter fell through. The type of repair is a “very common situation with mobile homes in the Lowcountry,” especially when they’re older homes, Gillis said.

The homes are often raised off the ground to avoid flooding, but skirting laid around a home’s base to keep out critters traps heat and humidity from the air and soil. That leads to mold and mildew, and the wood begins to rot.

Data indicate that Beaufort County’s low-income residents living in affordable housing may have an even more uphill battle because they cannot as easily afford the repairs or weatherization of their homes to combat the impact of climate change.

Climbing heat

Today, South Carolina suffers through 25 dangerous heat days a year, when the heat index rises above 105. A project by Climate Central predicts that number will rise to nearly 90 days by 2050.

Because many people in affordable housing balk at using air conditioning to save money, those high temperatures are not only a health hazard, they trap heat and humidity. That, in turn, can weaken building materials and lead to mold. It’s already happening, but experts say increased heat and humidity will worsen the problem.

Angela Childers, executive director of the Beaufort Housing Authority, said the threat of higher heat and humidity affects tenants who live in the county’s public housing.

Most Beaufort County residents are familiar with the hot, moist heat of the summer, when temperatures climb into the 100s. But many public housing tenants endure it without air conditioning, Childers said.

When Beaufort County’s public housing was first built in the 1980s, central air conditioning wasn’t included. If public housing tenants could find the cash, they had the option to buy a window unit themselves.

Now, the housing authority includes air conditioning units. But some renters are terrified of the high utility bills driven by running an AC unit.

“You don’t want to leave it on because you think, ‘I’m gonna turn that off because I’m saving electricity.’ Well, you turn it off, now you’re getting mildew because your windows are all wet,” Childers said.

Compounding that is what Childers said is increased flooding at the properties, with more renters saying they see and smell mold. High heat and water in enclosed spaces don’t mix well.

Rising seas

Over time, but mostly in the past five years, Childers has gotten more calls about flooded homes and maintenance requests because of septic overflow.

Increased storms and sea level rise both affect the ground’s saturation, in turn causing more flooding.

Sea levels have increased along much of the Carolina-Georgia coast by about 3 millimeters per year, on average, in the past century, according to previous reporting by The State Media Co. But in the past 10 years, sea level rise has reached 15 millimeters annually, with the rate projected to continue to increase, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association researchers.

In the next 50 years, NOAA expects sea level rise to increase by as much as 3 feet, or 18 millimeters a year. Along South Carolina’s coast, Climate Central predicts that by 2050 and under a continued high-carbon emissions scenario, the number of affordable housing units in the state exposed to flooding will increase seven-fold, from 62 to 474 exposed units.

District 3 Beaufort County Councilman York Glover said the residents he represents in St. Helena are already battling flooding issues.

“Sea level rise is the biggest issue for this district,” Glover said. “It’s going to have a negative impact on housing, period, whether it’s affordable or not.”

Deep Well has raised a home near the marsh 12 feet off the ground, but the group’s capacity to help only goes so far. Its services are limited to a 60-minute drive from the nonprofit’s Hilton Head office.

That doesn’t reach St. Helena.

And the snag remains whether a person can afford to raise their home or fill in the land.

‘Catch-22’ of affordable housing

The problems of coastal climate change also affect lower-income people who don’t live in affordable housing. Many who do not qualify for that housing turn to other low-income options, such as manufactured homes.

About 10% of Beaufort County’s households are in registered mobile homes, according to U.S. Census data.

More than 70% of mobile homeowners nationwide made less than $49,999 in 2022, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Beaufort County’s median house price in 2022 was $485,000, according to REsides, a multi-state Multiple Listing Service.

While the cost of a mobile home is far less, the cost of potential repairs can be daunting.

It’s what Clayton Evans, communications director at the Manufactured Housing Institute of South Carolina, calls the “Catch-22 of affordable housing.”

Today, a three-bedroom, two-bathroom manufactured home costs on average $73,000. It’s the same size of Hamilton’s house. It’s an attractive price for a lower-income home buyer. But the repairs, especially when it comes to humidity and storm damage, can be an absolute gut-punch. It’s left hundreds living in affordable homes in Beaufort County to endure unsafe conditions until they can pay the bill or get financial help.

Costs range from around $500 for a small floor repair to $9,000 to build a lift for a mobile home that needs to be raised because of flooding concerns, Gillis said of her records.

And climate-related issues can be even worse if the home was built before federal codes were enacted, Evans said.

In 1976, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development slapped codes on the mobile homes – including a requirement that they be anchored to the ground – and changed the name to manufactured homes. Since then, their quality and resilience against the elements have been greater.

Evans said the manufactured homes sold today are safe and affordable options, especially because most are raised several feet, and all of them are anchored.

However, he estimated that nearly all of the mobile homes on Hilton Head Island were built pre-1976. That means they’re particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, because they’re not built to withstand high winds, heavy rains and excessive flooding.

Even under codes, mobile homes are the “most vulnerable to climate change hazards,” said B.D. Wortham-Galvin, an associate professor at Clemson University’s School of Architecture.

Hurricane hardships

In the 1970s, Cleveland Williams was one of the first registered Navy paramedics in Port Royal.

By the mid-1980s, he had his sight on about an acre of lush green land with views of the Atlantic. He planned to live in a manufactured home until he’d raked in enough income to build a house. When he bought the double-wide, his land had 96 trees on it — among them live and water oaks, and a grapefruit tree.

Now, Williams said he has 22 trees remaining because of significant and increasing storm damage. He’s pulled out most of the sopping water oaks, but many were lost to hurricanes and high winds.

It’s clear to Williams that the number of storms and their intensity have increased. It’s been that way since Hurricane Hugo leveled parts of South Carolina in 1989, he said.

Strong winds and hurricanes are only projected to increase in strength, according to NOAA. As the climate changes, the administration predicts an increase in Category 4 and 5 hurricanes. Warming seas also generate wetter hurricanes, bringing 10-15% more precipitation from storms, NOAA data show.

Williams said he can see three-story oaks bend during tropical storms, and sometimes the limbs fall onto his fence.

Last summer, one fell onto his roof, caving it in and destroying the chimney.

“When you come home and see the devastation, it’s not motivating,” Williams said. “When you have to constantly do it over and over, consecutively back to back, it’s very disappointing and then imposes a real hardship.”

They’re hardships few people living in affordable housing can financially endure.

The cost to mend his caved-in roof, crushed chimney and cracked deck? $8,000. It’s money that Williams, living on a fixed income, didn’t have immediately.

During the summer, he worked with Deep Well to get his home back to safe, livable conditions. He’s on a payment plan. A neighbor living in a manufactured home in front of him and another across the street weren’t so lucky. They were forced to remove their homes because of tree damage caused by storms.

While Gillis said mobile homes are a great short-term solution to affordable housing, using them for long-term solutions is particularly “frightening” because of hurricanes.

“If we do get a hit like we got in 2016 from Hurricane Matthew, we know which houses are going to not do well with that, and it’s going to be the mobile homes,” she said.

What’s being done

There’s no magic answer on the national, state or local levels for addressing climate change’s predicted impact on affordable housing.

National experts want to focus on making affordable housing more energy efficient. Upfront, Clemson professor Wortham-Galvin said this plan would cost more for homebuyers and manufacturers, but in the long run, it’d be much more cost effective for the homeowner.

She’d like to see affordable homes weatherized, all electric-powered and retrofitted with renewable energy.

But Beaufort County is a long way from such an effort.

The county is working on a stormwater study to monitor sea level rise, which will indicate its most-vulnerable areas. Councilman York said the results, expected in the fall, will give an idea of “best management practices.”

The Beaufort-Jasper Regional Housing Trust Fund, established in October, is aiming to address the need for affordable homes for working families across the Lowcountry by creating more housing.

The president of Together Consulting, a group advising the trust fund, said it at the point of working out the bylaws.

Tammie Hoy Hawkins, the president, said the group is partially relying on building codes to protect against climate change, but she couldn’t say whether the codes would be effectively address potential housing issues that could arise from higher heat, rising seas and increased storms.

“The codes are there for a reason,” she said. “They are meant to protect the housing and the investment of that infrastructure.”

Ensuring that affordable housing is in good condition is just as important as creating new housing options, said Barbara Thomas, Lowcountry Habitat for Humanity’s interim executive director.

“It’s very vital for us to keep that existing housing stock in good repair,” Thomas said.

She said the issues are so pressing that Habitat for Humanity is in the process of establishing a program to repair homes, similar to Deep Well’s, that would help homeowners stay put, safely.

To stay or go?

On an unusually warm February morning, Audrey Hamilton was helping Deep Well volunteers put back her bedroom furniture and the red couch that made the latest hole in the floor.

Fresh gray vinyl now lines the room – it’s the same that was used in the kitchen.

For now, Hamilton’s floors are patched and safe for her and her grandchildren. Despite the consistent repairs to the home and potential threat of more in the future, she has no intention of leaving the place she’s called home for nearly 30 years.

Forty minutes away, Cleveland Williams walks his property with his chocolate lab Hershey. Hershey has been by Williams’ side through storms and their wreckage; his owner pulling up tree trunks, trimming branches and participating in neighborhood cleanups.

It’d be hard to leave, Williams said. But the upkeep as storms become stronger and more frequent may be even harder.

“It’s a lot of work to try and maintain,” he said.

Not to mention a lot of money. He’s still paying off thousands for the roof and partial deck repair.