This Rotary-Engine Sedan Was a Revolution (and a Total Failure)

Fewer than 38,000 of NSU’s revolutionary Ro80 models were built in the 10 years between its debut late in 1967 and the day in 1977 that NSU’s corporate parent, Volkswagen-Audi, turned the factory that built them over to Porsche 924 production, thus laying the NSU brand – which dated back to the 19th century but was merged into Audi in 1969 in desperation following the Ro80’s inauspicious launch – to rest. Though NSU’s dramatic move upscale proved a business disaster by most traditional measures – reliability, sale-ability and, above all, profitability – the Ro80 lit a path that many cars would follow and is still held in high esteem today.

It is, according to author and automotive historian, Englishman Martin Buckley, despite several shiver-inducing weaknesses, a wonderful machine, arguably one of the noblest of automotive history’s dismal failures. Accordingly, he supposes his volume “NSU Ro80: The Complete Story,” Marlborough, Wiltshire: The Crowood Press, Ltd., 2023, pp. 176, $43.99 (US) is the first English-language book-length appreciation of the machine. In it, he makes the contrarian yet convincing case for its having been “a masterpiece” with wit and style.

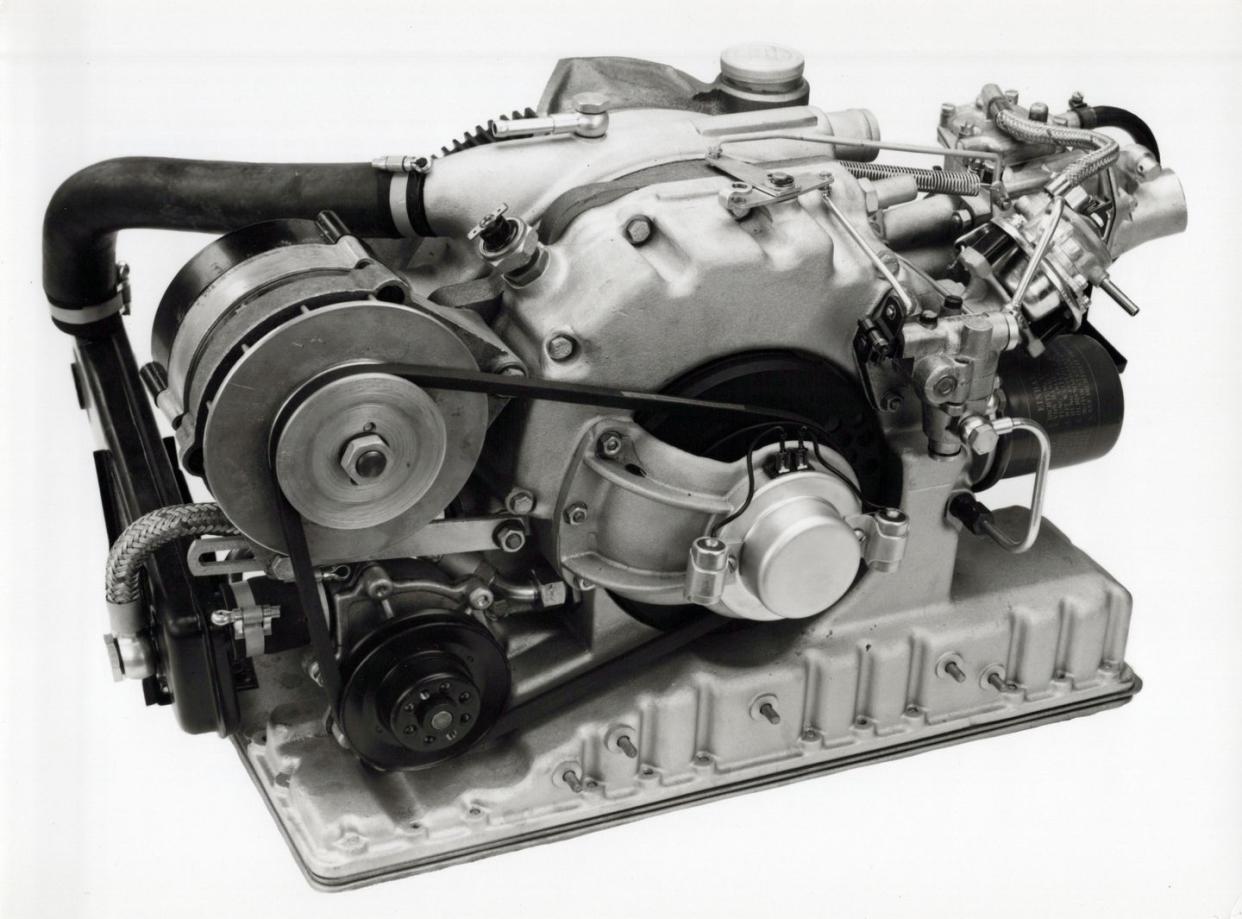

Consider – the first ever family sedan purpose built around a twin-rotor Wankel engine, with class-leading aerodynamics, fully-independent suspension and modernism all about it. Front-wheel-drive, four-wheel disc brakes, in-board at front. Superior outward visibility in all directions. An early, two-pedal manumatic gearbox. Known in Porsches as the Sportomatic, a microswitch found in its gearlever triggered its vacuum-operated clutch. Heady stuff for 1969.

Consider also – the Wankel engine, NSU’s baby. (Dr. Felix Wankel started consulting to NSU, at that time the world’s largest maker of motorcycles, in 1951.) Prone to burning its rotor tip seals to smithereens in 15,000 miles or less, causing power loss, plus untoward smoking, difficult starting and unusually excessive fuel consumption (economy never being a rotary strong suit.) Indeed, Buckley relates, some cars ended up with as many as nine replacement engines before their warranties expired. In fairness, he points out, no one ever did have complete success with the Wankel motor, though more than a few would try. But when it worked, it was notably smooth and powerful, making the hoary European Ford V4 that many a frustrated Ro80 owner inserted in the rotary engine’s place a cruel irony. A gruff and ornery lout, it was, alas, one of the only internal combustion devices capable of fitting in an engine bay designed for the diminutive rotary, whose genteel and effortless smooth was its greatest calling card.

NSU, which like many a legacy car brand began as a maker of bicycles and later sewing machines, didn’t survive, though its legacy carried on, clearly seen in the aerodynamic adventurism of the Audi 100s of the 1980s. Amusingly, though it wasn’t designed in a wind tunnel, Klaus Luthe, father of the Ro80’s design, had crafted a slippery silhouette by eye, which subsequent testing bore out. With a low nose and a high tail, it proved 35-40% more aerodynamic than most of its contemporaries. But, while winning Car of the Year honors in 1968, its soon-to-be-realized market failure may well have discouraged true technical adventurism for German makers, Buckley opines. For the Ro80’s unique specification -- though emblematic of a period when the German industry’s confidence in its engineering and ability to blaze new trails was at an all-time high -- shook that sense of certitude.

While telling the Ro80 story, roses, thorns, bee stings and all, Buckley offers up an engaging pocket history of NSU, including its long if not always jolly association with Fiat, its considerable, if less than admirable, contributions to the Nazi war effort and the company’s recovery from war, with many of its ex-Nazi engineers and executives quickly restored to positions of prominence. The 50s were an exciting time around its Neckarsulm factory, with much racing success for its motorcycles along with many records set at the Bonneville Salt Flats. Its mopeds sold briskly, too, while a post-war return to car manufacture with the surprisingly advanced two-cylinder air-cooled Prinz model gave the VW Beetle a run for its money, with better handling and performance, despite their comparatively small engine capacities.

Larger displacement four-cylinder models that followed offered still more performance helped keep pace with a growing European middle class. Heartening success in touring car racing and hill-climbing also ensued, but before long the air-cooled, rear-engine cars were increasingly seen as outdated, called on to hold down the fort against the arrival of the paradigm-shifting front-drive NSU K70 (later released, albeit haltingly, as a Volkswagen.) Once again, NSU would point the way forward for VW, before it got kicked to the curb. Meanwhile, deliveries of the world’s first rotary-powered car, the two-seat NSU Wankel Spider, begun in 1964, graphically demonstrated the potential limitations of the Wankel powerplant, an expensive exercise in beta testing that the Ro80 was meant to benefit from, but did so insufficiently.

Speaking of which, Buckley’s history of the Wankel engine itself is fascinating. A cranky, self-taught engineer with an honorary doctorate awarded years later who didn’t drive owing to poor eyesight, Felix Wankel dreamed up the rotary engine’s guiding principles in the 1920s, but for a long time his greatest contributions were thought to be in the sealing of engines. An enthusiastic member of the Hitler youth movement as a young man, his workshops were destroyed by the French at the end of the War and a prison sentence ensued. He wound up in the early 1950s at NSU which, in Buckley’s phrase, helped tame his ideas. In fact, Wankel himself was kept at arm’s length from the development of practical working prototypes by the company which would fatefully agree nevertheless to fund its development.

For instance, the curious doctor had imagined the engine’s rotor and casing both rotating while cooler heads suggested that the rotor circulate in a fixed casing. “You have made a cart horse out of my racehorse,” Wankel thundered. “If only we had a cart horse!” NSU’s top executive and a rotary booster, Gerd Von Heydekampf, replied. As much as possible, Wankel, though admired, was kept away from the business of practical engineering.

Nonetheless, the storied company bet all its marbles on his idea only for it to become its swan song, at once a tribute to its native engineering smarts and ambition along with its gravest mistake. For a time, there was hope the Wankel engine, much more sorted by 1972, would find a home in the Audi 100 – several test mules were built – but as Audi moved upscale that hope was found to lay mostly with NSU personnel. And yet, NSU’s positive effect on Volkswagen and its future engineering direction is inarguable.

Reading like a fine magazine article -- not surprising as Buckley’s reviews and columns have been delighting readers in Britain’s Classic and Sportscar and EVO magazines for decades -- “NSU Ro80: The Complete Story” serves to remind us of a time when there were companies willing to bet all the marbles on something new. Not unlike Buckley, who’s owned five Ro80s himself.

You Might Also Like