The Rise of the Anti-Fame Celebrity

Waffle House has a number of employee benefits. Unlike musicians, Waffle House employees are entitled to health care, dental insurance, parental leave, perhaps a couple of free waffles every now and then. Your boss might even grant a last-minute leave of absence so you can headline Lollapalooza. Such was recently the case for a Waffle House employee named Lana Del Rey, a waitress stationed in Alabama who attends men-in-music-business conferences on the weekend and longs one day to be a star. Waitress first, musician second—that appears to be Del Rey’s dream.

To back up here for a moment: In September, Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey was spotted serving up coffee at a Waffle House, working at the chain on consecutive days, and taking selfies with astonished fans. This year, a number of celebrities have enjoyed similar spells as service workers. The world’s most famous and fervent Dunkin’ Donuts regular, Ben Affleck, served iced coffees from a takeout window at a Massachusetts location in February. In July, David Letterman revisited his roots as a supermarket shelver, putting in a day’s work at a Hy-Vee in Des Moines. But while those two stints turned out to be nothing more than high-paying commercials, Del Rey’s appeared to be entirely for her own gain. This was not a marketing ploy. In fact, Waffle House hasn’t posted at all about Del Rey’s employment.

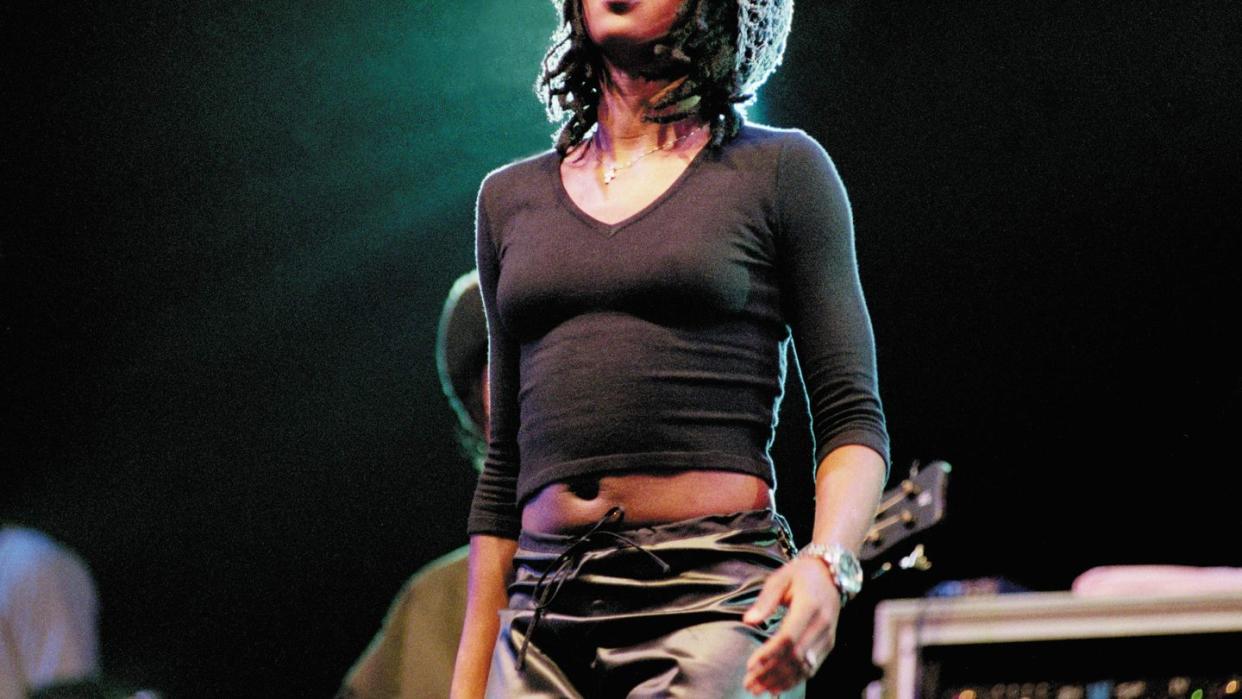

“Fame, liquor, love / Give it to me slowly,” she sang on her 2012 single “Gods & Monsters,” drawing out that faaame as though in sexual rapture—half agony, half dream. Over a decade later—a decade spent ravaged by fame—it seems there’s nothing Del Rey longs for more than her life before it. After releasing 2019’s Norman Fucking Rockwell!, an album generally considered her magnum opus, she has been looking back on her days in food service. “When I was a waitress, wearing a tight dress,” she sang on her 2021 follow-up, as orgiastically as her earlier craving for fame.

This shift in desire appears to be representative of a culture where female songwriters in the spotlight increasingly long for a life before celebrity. A regular at Rhode Island’s annual Newport Folk Festival, as well as Walmart and the Waffle House, Del Rey has been unofficially anointed the anti-fame guru of a newly fame-skeptical culture. She has never been subtle in her desire to be canonized within the tradition of great singer-songwriters who have evolved outside of mass culture while still profiting from it, so for her in particular, it’s a posture that lends an air of authority and authenticity to her work. Like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell before her, Del Rey and the new class of fame skeptics are publicly struggling to reconcile the relationship between celebrity and auteur, art and commerce, the consequences of creativity and its co-option into an exploitative, capitalist-dictated marketplace.

For today’s artists, it takes extra work to get in the studio and forget the audience that exists outside of its walls; to forget data points, and streams and the logic of consumption. It takes work to return to a childlike love of music, to still behave like a human and not an algorithm, pure in intention and uncorrupted by the industry.

The Waffle House represents this desire for pre-fame purity. The Waffle House is a place of all-American homogeneity, uniformity, conformity, anonymity—a place where hierarchy and the distinction between the famous and mundane are collapsed. “Nobody in this Waffle House knows who I am,” rising-star singer-songwriter Ethel Cain told The New York Times in an interview last year, explaining why she’d chosen the location for her highest-profile interview yet. That too was a Waffle House in Alabama, a place, Cain said, where she could “remain a local.”

Since the unexpected success of her 2022 debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, Cain has experienced the degrading effects of fame, her humanity refracted back to her via her own memeification, as TikTokers soundtracked photos of Kim Kardashian outfitted in a pilgrim-y get-up with Cain’s “A House in Nebraska,” and the extremely online literate have used her songs and image as shorthand for a gloomy sylvan existence. In response, Cain felt herself “a dancing monkey in a circus,” she told The Guardian in July.

Many such profiles of musicians today focus on the downsides of early-onset fame; perhaps we’re simply more tolerant of these “fame is a prison” narratives. Previously, one of the worst things about attaining fame and fortune was that everyone stopped feeling sorry for you. Now, fame seems to elicit its own kind of pity.

Perhaps the disturbing knowledge of Britney Spears’s conservatorship undergirds all of this. Ever since The New York Times released Framing Britney Spears in late 2021—a film that essentially functioned as a reassessment of Spears’s entire career in light of her legal battle against her father—this culture of anti-fame has accelerated, and with it has come our own reckoning with how we treat the very famous. It’s something that those on the precipice of fame are now cognizant of, too.

“I think that’s a really interesting thing to think about,” Tiktok personality Addison Rae told Bustle in a 2021 cover story, in response to the interviewer’s question about whether she had seen the documentary. She went on to say, “I definitely can see how that is an overwhelming life. People do come up with narratives around you that aren’t necessarily true. I’ve kind of dealt with that a lot, people being involved in really personal aspects of your life.”

As a form of protection, aspirations for fame have been replaced with aspirations for obscurity. It’s no coincidence that Del Rey has increasingly strived to make her songs as unintelligible to outsiders as possible, limiting her lyrics to full names, inside jokes, and references only she and her inner circle could comprehend—obscuring her accessibility through observant specificity. Even her metaphors—a literary device traditionally intended to open up one’s world more than any other—are deliberately inefficient. What is the significance behind her latest two album titles, for instance? Only Del Rey could meaningfully tell you.

Twenty-five years ago, Lauryn Hill—who made one of the greatest albums of all time and then proceeded to swiftly peace out from the spotlight—arguably set the blueprint for anti-fame. Right after capturing the zeitgeist with her one-and-only solo album, 1998’s The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, the Fugees frontwoman withdrew from the public eye, explaining in an interview with Essence in 2006 that her artistry and integrity had been at odds with an industry “designed for consumer mass appeal and dictated by very limited standards.” Those industry-set standards are even narrower for Black female artists; Hill refused to sacrifice her truths and enormous heart for them.

Today, Doja Cat is messily grappling with the same issues. Fame has made her antagonistic toward a culture fueled by parasocial relationships and a fanbase hell-bent on making her small enough to consume. In return, the rapper has become increasingly reactive, acting out her confused relationship with fame and the compromises it entails in a trickster persona, spreading mischief and chaos everywhere she goes.

It’s not just celebrities. Now that everyone is subject to a predatory hyper-surveillance culture, with advertisers targeting and mining us for data the way paparazzi swarm celebrities, more of us are sympathetic to the effects of fame. Today, everyone can be a victim of too much attention. A passerby, for instance, may film you at your drunkest and highest, turning you into a brief viral talking point. Even waiters and waitresses can elicit their own kind of fame; as public actors they are defined by and limited to a persona that the people they are serving expect from them.

Recently, while speaking on The Julia Show, Olivia Rodrigo shared that she and co-writer Dan Nigro had considered cutting the term fame fucker from the chorus of her recent single “Vampire.” Instead, she kept it in, explaining: “I think that’s a universal theme, and I also think fame is more easily accessible now than it has ever been. It’s not just people in L.A. and Hollywood that have to deal with that.”

On “Vampire,” Rodrigo sings over a pared-back piano line reminiscent of Carole King, a ’70s singer-songwriter who privileged her home life over celebrity, and who serves as a common inspiration for many of today’s anti-fame artists. Like King’s, Rodrigo’s vocals are a master class in manufactured idiosyncrasy. Every note sounds as though she’s violently surrendering breath, as she lets the spontaneous rise of emotion dominate the flow of her performance.

As demonstrated by the first two singles from her new album—the follow-up to “Vampire,” “Bad Idea Right?” is a pastiche of ’90s riot-grrrl rock—Rodrigo is drawing from the musical templates of alternative, anti-commercial, anti-fame epochs. Whether Carole King or Joni Mitchell, Le Tigre or Nirvana, these eras confronted the issue of selling a commodity through anti-capitalist valence—a contradiction that musicians are returning to today.

“Who am I if not exploited?” Rodrigo asked on her 2021 debut album, setting that standard for her fame-skepticism. It was a lyric spiritually in line with Florence and the Machine’s 2022 single “King,” on which Florence Welch sings about the issue at the heart of her art-making today: “And how much is art really worth? The very thing you’re best at is the thing that hurts the most.” Likewise, on 2021’s “Getting Older,” Billie Eilish lamented that “things I once enjoyed / Just keep me employed now”—a sentiment she explored further on this year’s Barbie soundtrack single “What Was I Made For?” It’s a song somewhere between a Broadway musical number and a Laurel Canyon ballad, in which Eilish puts on a breathy vocal similar to Rodrigo’s on “Vampire” and Del Rey’s on “White Dress,” to sing: “Turns out I’m not real / Just somethin’ you paid for.”

Time and again, (particularly female) celebrities have repined the blurry disconnect between their public and private selves, once they’d found themselves appropriated into a commodity that could be claimed by the public. After the success of “Nothing Compares 2 U” in 1990, the late Sinéad O'Connor told an interviewer that fame had caused her to forfeit much of her subjectivity. “As soon as I went to number one, everything went mad. I went from a person to a product,” she said. In 2014, when Beyoncé released her retrospective film Yours and Mine, she described herself as a “property of the public.”

Post-pandemic, more and more women had begun weaving these complaints into the songs themselves. In 2022, Mitski released “Working for the Knife,” a song entirely dedicated to the seemingly impossible task of making art within an extractive and exploitative environment.

We can now actually relate to celebrities complaining about fame. Previously, few of us paid attention to the labor and machinations behind the pop star. We fetishized them, alienated them, believing them to be autonomous beings who existed in opposition to workers. Now, a Waffle House worker can soon become a celebrity and a celebrity can soon become a Waffle House worker. No longer are we yearning for fame, but a world without it.

You Might Also Like