How RFID Chips Are Bringing Next-Gen NFL Stats Right to Your Couch

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Football stats are more advanced than ever, with RFID cards embedded in player uniforms and footballs.

RFID sensors track player movement as well as the movement of the ball itself.

Hundreds of data points can be used to enhance video games, player stats, and player safety.

It was first and goal for the Seattle Seahawks during a 2020 game against Arizona. Cardinals safety Budda Baker jumped the lane to snare an interception, tearing off for the end zone, but Seahawks wide receiver D.K. Metcalf—who was running on the opposite side of the field—gave chase. In an amazingly short time, Metcalf brought down Baker short of the goal line, saving a touchdown. “He is flying down the field,” Cris Collinsworth said during the broadcast. “It was unbelievable how much ground he made up!”

🏈 You love sports tech. So do we. Let’s nerd out over it together—join Pop Mech Pro.

Within minutes, we knew just how fast Metcalf was. He’d covered a total of 114.8 yards during the play, reaching a top speed of 22.64 mph. Those numbers are courtesy of the NFL’s Next-Gen Stats, offering data in real time based on player (and football) tracking on the field. In fact, we know that Metcalf was one of the fastest players of the year, according to Adam Petrus, business development and sales lead for sports and entertainment at Lincolnshire, Illinois-based Zebra Technologies, the official on-field player-tracking provider for the NFL. “That told an interesting story, and that’s the sort of thing the NFL loves to do,” Petrus tells Popular Mechanics.

An important part of any football game is data collection and analysis. Yards-per-carry or yards-per-pass are tracked on offense, as are tackles and sacks on defense. In the press box, teams’ media relations staffs pass out reams of paper with every countable metric, from snap counts for players to a chronology of every play during the game.

D.K. Metcalf reached 22.64 MPH and traveled 114.8 yards to chase down Budda Baker on his 90-yard interception return (Baker's top speed: 21.27 MPH).

This was the 2nd-fastest speed reached on a tackle this season.#SEAvsARI | #Seahawks | #RedSea pic.twitter.com/nyX0Y16LQz— Next Gen Stats (@NextGenStats) October 26, 2020

And an imperceptible network of RFID sensors track player movement as well as the movement of the ball itself, with the potential for more than 260 data points for any play during an NFL game—all collected in real time. It’s part of the league’s latest efforts to compile data not just for teams to analyze and interpret, but to help enhance the fan experience as well.

“The advancement of technology is a positive for the game. The next step is to figure out what to look for to try to get that advantage,” Petrus says. “Sports and technology are coming together. It’s really for the teams to see what the data means.”

Tracking Players Through Radio-Frequency Signals

For as long as the NFL’s been in existence, coaches and front office personnel have been refining data gathering and player evaluations. In the 1940s, the Rams, who’d just moved from Cleveland to Los Angeles, didn’t have a network of former players to recommend players to sign. So owner Dan Reeves started the first official scouting department in the NFL, tasked with finding new talent.

Paul Brown, the founding coach and namesake of the Cleveland Browns, revolutionized player development by timing players running the 40-yard dash (he said it was reflective of the distance a player would run on punt coverage). It’s a test still done today at the NFL Combine—itself formed in the 1980s to give teams a clearinghouse to meet with players and track their statistics.

With the popularity of the NFL and the advances in technology, by 2008 it seemed natural to start looking into player tracking on the field. But there was one hitch: cameras, the commonly used way to track players, wouldn’t catch all the information.

“It’s very difficult in American football to map player placement just with cameras, just because there are so many different people on the field,” Matt Swensson, head of products and technology for NFL Media, tells Popular Mechanics. “You can do it with other sports, but it just didn’t give us the results we needed.”

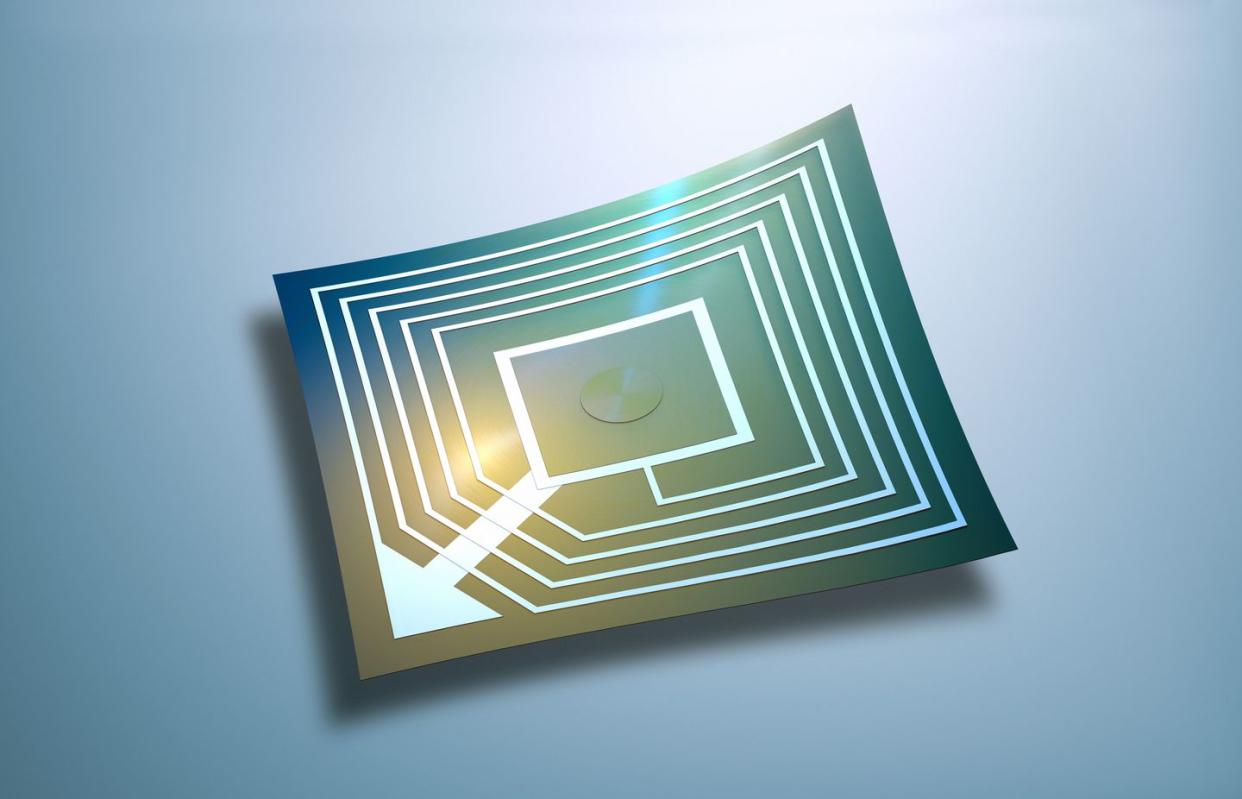

Zebra Technologies submitted a proposal using Radio Frequency Identification (RFID). The technology uses tags that emit an electromagnetic signal which nearby receivers pick up. Zebra’s main business at that point was asset tracking, using similar technology to track items along the supply chain, for example, or in manufacturing.

The proposal won out, and Zebra set up receivers not just in every NFL stadium, but in stadiums where NFL teams might play, like Tom Benson Stadium in Canton (home of the annual Hall of Fame Game) and venues in Europe or Mexico that host games.

Players wear two RFID tags, between layers of pads on each shoulder. For down linemen—the players who set up in a three-point stance, with one hand on the ground—another tag is placed in the middle of the shoulder pads on the back. Those help locate each player’s center mass.

Each tag, which has enough battery power to last an entire season, is about the size of a nickel. “The players don’t even know the tags are embedded into the shoulder pads,” Petrus says.

The RFID tags debuted on players in 2014. Getting tags into footballs was a little trickier. That’s one of the reasons Andrew Wentling has the job he has.

Wentling manages the factory that makes Wilson footballs in Ada, Ohio. The factory turns out 600 balls a day, ranging from high school balls to the Duke, the model that’s been used by the NFL for nearly its entire history. (A recent trip saw a bin full of footballs in the unique Tiffany blue, part of a partnership between the NFL and the jeweler, which also makes the Vince Lombardi Trophy awarded to the Super Bowl winner.)

He’s a native of the area (the nearby town of Carey, to be precise, home of the Division VI high school football champions) and is a product engineer by trade. Prior to being hired by Wilson in 2015, he worked for Bridgestone, designing polyurethane foam seats and energy-absorbing pads for side impact that accommodated sensors and air bags. As it turns out, that was just the skill set needed to help put the RFID tag into the football.

A football is an inflated bladder covered by cowhide; the term “pigskin” is actually a misnomer. The RFID tag is around 3.5 grams, which might not mean much to a 250-pound football player, but it’s a significantly bigger deal to place in a football that weighs less than a pound—particularly in a manner to keep it from moving and throwing the ball off balance.

Ultimately, the sensor is suspended in the bladder—on the side opposite the valve where the ball is inflated. “We encapsulate the sensor and attach it to our bladder, and then we weld a perimeter seal and everything’s encapsulated inside,” Wentling tells Popular Mechanics.

The RFID tag is higher-frequency in the ball, at 25 hertz per second, than on the players, at 12 hertz per second. The higher frequency enables measurement of rotation per minute, velocity, and acceleration. The first balls with RFID tags were used in the 2016 preseason and on Thursday Night Football. Starting the following season, every game ball had the tag, which worked well enough that the balls were out of circulation before the tag’s battery wore down. (The average lifespan of an NFL game ball is around six games, Wentling says. Then they’re rotated out for practices, where they can be used for another year or two.)

Being the manufacturer of the NFL football is a point of pride in Northwest Ohio—and Wentling takes as much pride in being able to successfully install the sensor and the data that resulted. “Before the sensor was in the ball, they could track speed and closure, but the data was incomplete,” Wentling says. “Now they can tie everything together: routes, speed and closure.”

But what do you do with all that data?

From the Football Field, to the Virtual Field

One of the initial uses for the data was related to the media. “We wanted to get information online, for broadcasts and data for fans,” Swensson says. “Many uses are behind the scenes. If we wanted to identify every player JJ Watt lined up against and got to the quarterback against, we could do that. It’s very helpful when we’re putting together highlights.”

Already, next-gen stats are being incorporated into video game development. Swensson says that EA Sports is using the data to create more realistic versions of Madden, the popular football video game. (Previously, the company relied on an algorithm, Swensson says.) For example, RFID data may show Cooper Kupp changing his stride while making a cut on a route. That can be incorporated into next year’s Madden. “It allows another layer of realism in a virtual experience,” Swensson says.

And while cameras couldn’t solve the problem in 2008, Swensson says that cameras paired with RFID sensors can bring even more realism into virtual experiences. The sensors can identify center mass on a player, but cameras can track where a player’s limbs are as well as skeletal alignment when players are running or jumping.

“You can get new metrics and new insights when you add in cameras,” Swensson says. “I’m confident that a combination of cameras and RF solutions can get even more data.”

Initially, the data was shared on a limited basis between teams. If, say, the Giants and Eagles played, the next-gen stats from that game would only go to those teams—and one game can generate gigabytes of data. Part of that was to keep NFL front offices from being overwhelmed by data. Every play is tracked (teams typically run between 60 and 65 offensive plays per game—a stat that’s stayed remarkably consistent over decades), and Swensson said the game information for one team from one season is greater, in hard drive space, than all the records kept by the league since its founding in a Hupmobile dealership in Canton in 1920.

But starting in 2019, every team got next-gen stats on every game. “It was a slow rollout to ensure clubs were getting ready to use it,” Swensson says. Now, every team has a data evaluation group, looking for that competitive edge.”

The data could also help player health and safety, Petrus of Zebra Technologies says, noting that it’s finally possible to quantify what constitutes a hard practice, in terms of player load, exertion, speed, and sustained speed. Petrus says it could be possible to see tapering practice for football players, like runners and swimmers do leading up to big events.

And of course, there’s gambling. As recently as 2018, Nevada was the only state with legalized sports betting. Now, not only are states rushing to get in on the action, but leagues are actively partnering with gambling interests. The Arizona Cardinals are expected to become the first NFL team with a sports book in the stadium this fall, and more are sure to follow.

For now, around 75 percent of wagers are on the game’s outcome—either a moneyline or involving a point spread—but prop bets are on the rise. Those are the bets most people see around the Super Bowl, for example: the length of the national anthem, the result of the coin toss, even the color of Gatorade the winning coach is showered with. They’re not offered a lot in-game, just because of the paucity of data available, says Steve Ruddock, senior gaming analyst for Wagers.com and editor-in-chief of Gaming Law Review.

But that can change. The NFL announced in 2021 that it’s partnering with Genius Sports Group to distribute NFL’s play-by-play, betting, and Next-Gen Stats data feeds to global media and gaming markets.

“Next-gen stats are a growing part of the overall sports betting landscape and will be a critical piece of sports betting going forward,” Ruddock tells Popular Mechanics in an email.

“There’s going to be a day when you can watch the game and pull up all this data in real time on your phone,” Wentling, the manager of the football factory, says. “You’ll probably be able to bet how fast someone runs their route.”

You Might Also Like