What can replace coal’s impact in Eastern Kentucky economy? These industries are growing

In 1964, then-President Lyndon B. Johnson asked the U.S. Congress to declare an “unconditional war on poverty,” aimed at making places like Eastern Kentucky more prosperous and economically healthy. Now 60 years on, what kind of impact has Johnson’s war had on Appalachia? The Herald-Leader will explore this topic over the next few months. Have story ideas for us or want to be a source? Email reporter Bill Estep at bestep@herald-leader.com.

Justin Phillips, of Letcher County, had worked at fast-food restaurants and convenience stores for relatively little pay, sometimes holding down two jobs to get by, before he started a program in February to do remote tech support for Apple.

Phillips, who is married and has three children, said the job pays more than anything else he could get in the area.

“We’re making ends meet now,” said Phillips, 34. “I’m dead-set on making this a career.”

Phillips is an example of efforts to transition the economy in Eastern Kentucky after a century of dominance by the coal industry.

That transition has been going on for years, but the work took on increased urgency after coal jobs plunged by a third in 2012 and kept going down for several years.

Eastern Kentucky had endured booms and busts in coal production for decades, but with no real hope the industry will ever again employ as many people as it did in 2011, leaders and residents in the region are pursuing opportunities in other fields to boost jobs.

There has been some success, but the effort also faces challenges, including population loss, low participation in the labor force and gaps in broadband service.

However, with the potential for significant federal funding for diversification efforts and a determination not to let the region wither, many people believe Appalachian Kentucky is at a unique moment to make progress 60 years after President Lyndon B. Johnson asked Congress to declare war on poverty.

‘Took the place of coal’

Leaders from government, non-profit organizations and the private sector believe there is potential to increase jobs in several fields, including healthcare, remote work, small retail and tourism.

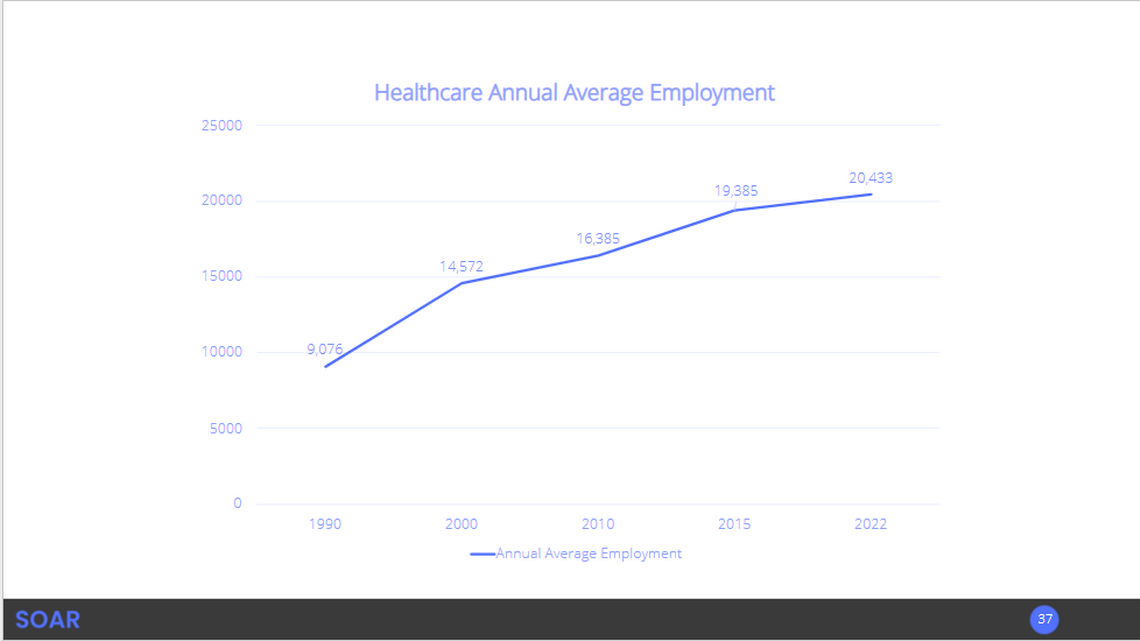

There already has been considerable growth in health care.

In 2003, there were just over 20,000 jobs in health care in 23 counties where the Eastern Kentucky Concentrated Employment Program provides job training and placement services, according to the agency.

In 2023, that number had increased to 25,933, even as mining jobs in those counties dropped nearly 70%.

A separate analysis by Colby Hall, executive director of Shaping Our Appalachian Region (SOAR), found healthcare jobs in 12 traditional Eastern Kentucky coal counties in the first quarter of this year far outstripped jobs in other fields.

There were 7,854 people employed in healthcare, followed by retail at 4,756, public administration and educational services at 4,504, and just 749 in mining.

The counties were Bell, Floyd, Harlan, Johnson, Leslie, Letcher, Knott, Knox, Magoffin, Martin, Perry and Pike.

And with many jobs in the healthcare sector paying relatively well, total annual wages in the field had increased from $167.9 million in those counties in 1990 to $1.13 billion in 2022, according to the SOAR analysis.

Over that same period, total annual wages in the mining industry fell from $700 million to $280.8 million.

Health care accounts for more than 20% of all jobs in several Eastern Kentucky counties where coal once dominated, according to the Community Economic Development Initiative of Kentucky (CEDIK), part of the Martin-Gatton College of Agriculture, Food and Environment at the University of Kentucky.

Eastern Kentucky has an aging population and relatively high percentages of people with health problems, including diabetes, heart disease and some types of cancer. Jobs in healthcare have increased as providers moved to address those needs and to provide services that people once had to travel outside the region to receive.

Appalachian Regional Healthcare, with 12 hospitals in southeastern Kentucky and 5,500 employees, is the single largest employer in the region, and Pikeville Medical Center has added services and specialties, including a children’s hospital, autism therapy, and an expanded cancer center.

Donovan Blackburn, president and CEO at the Pikeville hospital, said it had 1,400 to 1,600 jobs in 2004, when he was city manager of Pikeville. Now it has about 3,700 at the main hospital and other clinics and facilities, and accounts for about half the occupational-tax revenue the city gets, he said.

“It took the place of coal,” Blackburn said of the healthcare sector.

‘Game changer’

There are fewer total jobs in Eastern Kentucky than two decades ago because of declines not only in mining but other industries as well, including retail trade and construction. But there has been growth in some sectors other than healthcare, including in educational services, remote work and tourism.

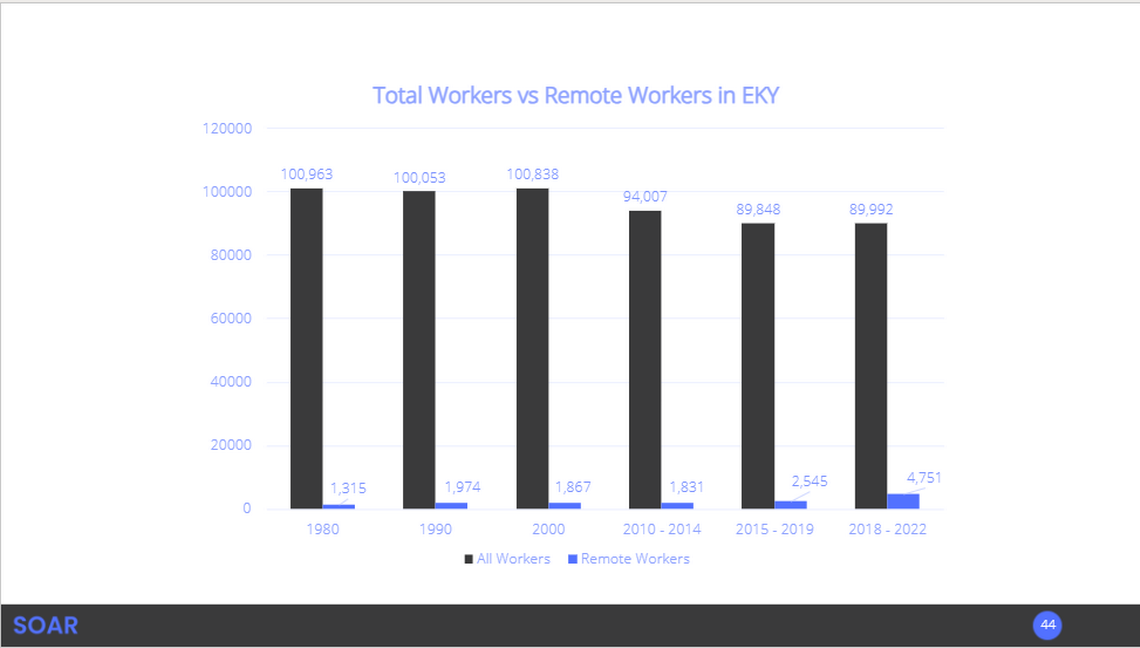

There were 4,751 remote work jobs in a 12-county area of Eastern Kentucky between 2018 and 2022. That was up from 2,545 between 2015 and 2019, according to information from SOAR.

The jobs include positions in customer service and technical support.

An increase in availability of high-speed internet has helped in that, though many people still don’t have access to broadband at home.

SOAR said in an application for a federal grant that 27% of households in the 12 counties don’t have access to broadband.

However, the state has received more than $1 billion in federal funding to expand broadband, and over the next several years, access will spread significantly, said Lonnie Lawson, executive director of the Center for Rural Development in Somerset, which is working to expand digital access.

The spread of broadband would create more opportunities for remote work, retail, education and other services.

“It’s a game changer,” Lawson said.

Jobs in the arts, entertainment and recreation field increased by 34% between 2003 and 2023, and jobs in the accommodations and food services sector increased 7%, according to information from the Eastern Kentucky Concentrated Employment Program.

Several cities in the region have had success in revitalizing their downtown areas, increasing the number of businesses and jobs — which helped drive a population increase in some cities even as the region lost population between 2010 and 2020 — and some people say there has been a change in the narrative that young people had to leave Appalachia to succeed.

‘A lot of things’

Development is underway on a number of tourism and outdoor recreation projects to join many already in operation.

The region’s heritage, history, natural beauty, forests and lakes and rivers make it a natural for tourism, promoters say.

The projects in the works include an observation tower in Harlan County near the state’s highest point on Black Mountain; Boone’s Ridge in Bell County, which will have wildlife viewing, an education center, an aerial gondola and other attractions; and in Letcher County, Raven Rock Resort and Thunder Mountain, a sport shooting and archery range.

The opening of Boone’s Ridge has been delayed from the original timetable, in part because of difficulties getting materials, but it will open in the summer of 2025, said Frank Allen, chairman of the Appalachian Wildlife Foundation, which is developing the project.

The attraction is projected to ultimately have more than 300 employees, Allen said.

The ARC recently announced Boone’s Ridge will benefit from a $9.3 million grant.

“We’re trying to piece together a lot of things” to diversify the economy, said Jeffery Justice, executive director of the Pine Mountain Partnership, a development organization in Letcher County.

Some of those projects wouldn’t have been considered before the demise of coal. The steep downturn in that industry has been painful, but helped open the way to explore other ways to boost jobs, Justice said.

“The demise of the coal industry has allowed us to think differently about our economy,” he said.

One key piece of that effort is making communities more attractive for people stay in or move to, including people who can work from anywhere, several observers said.

“It’s not about recruiting jobs to places. It’s about recruiting people to places, and they create jobs,” said Peter Hille, president of the Mountain Association, which is active in the economic transition in Eastern Kentucky.

Dee Davis, president of the Center for Rural Strategies in Whitesburg, said there is a good deal of innovation in Eastern Kentucky, with smart people working to make improvements.

“The most important thing is for people to make their towns places people want to live in,” Davis said. “The way industry works now is people bring jobs with their laptops.”

‘Enormous strides’

The work to broaden the economy in Eastern Kentucky continues 60 years after President Lyndon B. Johnson visited in April 1964 as part of his push for anti-poverty programs.

In his State of the Union speech in January that year, Johnson had asked Congress to declare “unconditional war on poverty,” and a broad range of programs approved in the years after that became known as the “War on Poverty.”

The programs included money for schools, Medicaid and Medicare, community action agencies aimed at helping lower income people, expanded housing subsidies, job training, food stamps and the Appalachian Regional Commission.

Eastern Kentucky was a starkly different place in the early 1960s.

In 1960, 58.4% of the people in Appalachian Kentucky were economically poor under the federal measure, compared to 22.1% nationwide, the Kentucky Appalachian Commission said in a report published in 2000, before it was disbanded.

The coal industry was in a down cycle at the time, with production in 1960 at the lowest point since the Great Depression 30 years earlier. Many miners were out of work, and thousands of people moved out of Eastern Kentucky in the 1950s and 60s to find jobs in Midwest industrial cities.

There were no four-lane highways through Eastern Kentucky and few water and sewer systems. Schools were chronically underfunded, and many people had little or no access to high-quality health care.

Federal, state and local governments and non-profits have since spent billions in the region on highways, schools, health facilities, housing, water and sewer systems, education programs and job training, and Eastern Kentucky is much closer to the rest of the country in economic and educational measures than it once was.

In the five-year period from 2017 to 2021, the poverty rate in Appalachian Kentucky was 23.1% — still higher than many places but considerably closer to the U.S. level of 12.6% than in the 1960s.

Per capita income in the region was 65.4% of the national level in 2021, up from 60.1% in 2007, and the high-school completion rate from 2017 to 2021 stood at 91.1% of the national level, up from 60.6% in 1980, according to the Appalachian Regional Commission.

“We’ve made enormous strides,” Hille said, while noting gaps remain and more work is needed to bridge them.

Programs approved in the 1960s remain relevant to the region’s economy and prospects, including education funding and Medicare and Medicaid.

The federally-backed insurance programs are key supports for the healthcare industry in the region.

In the payment mix for Pikeville Medical Center, for instance, Medicare and Medicaid make up 77% of the revenue, Blackburn said.

‘Once-in-a-lifetime moment’

There are challenges to improving the economy in Eastern Kentucky.

One is the population loss, which could further erode the workforce and put a damper on gains in healthcare.

“We’ve gotta stop that bleed,” Blackburn said.

The region can do more to keep people home, Blackburn said, pointing to a program the hospital is carrying out with several partners to increase the number of people pursuing healthcare occupations.

The number of people participating in the labor force also is low in Eastern Kentucky.

During the 2018 to 2022 period, only 42% of people age 16 and up were in the labor force in 12 Eastern Kentucky counties compared to 63% nationally and 60% in the state as whole, according to information from SOAR.

Relatively high rates of disability help explain that. So does substance abuse, though Kentucky is a leader in availability of residential treatment beds, with many of those in Eastern Kentucky, said Tim Robinson, president of Addiction Recovery Care.

But there also is “an overall lack of jobs that provide both family-sustaining wages and a longer-term career path,” said Hall, the SOAR director.

David Estep, 44, said that after he was laid off from a coal mine in 2019 after 15 years in the industry, he couldn’t find another good-paying near his home in Harlan County.

“I couldn’t find nothing, especially nothing that would even come close to paying the bills,” he said.

He completed a program through community college to become a utility lineman and had a new job before the end of the year with Pike Electric, which does construction and maintenance work on electric transmission lines.

The money is better than when he worked in the mines, Estep said, but his job is in Knoxville and he still lives in Harlan County, so he spends several days a week away from home.

Without the lineman job, he and his family would have had to move to find work, as many others have, he said.

Those focused on the economic transition in Eastern Kentucky want to make sure people don’t have to leave or travel for a job.

The region needs to attract many more jobs, but also needs to train people to be ready for those jobs, including opportunities in the renewable energy sector, several said.

SOAR is a finalist for a federal grant of up to $50 million to help improve skills for thousands of people in Eastern Kentucky, including training for remote work jobs.

Building the workforce and economy in Eastern Kentucky won’t be quick or easy, but development leaders say they are optimistic it will happen.

One reason is a massive increase in federal funding — through measures such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law — available for programs and projects in clean energy, broadband, environmental cleanup and other areas that could benefit Eastern Kentucky and Appalachia.

“This is the biggest increase in funding for Appalachia since the War on Poverty,” Hille said. “Unquestionably it is a once-in-a-lifetime moment.”