Removing the 'legacy of slavery': Fort Lee gets renamed over 150 years after the Civil War

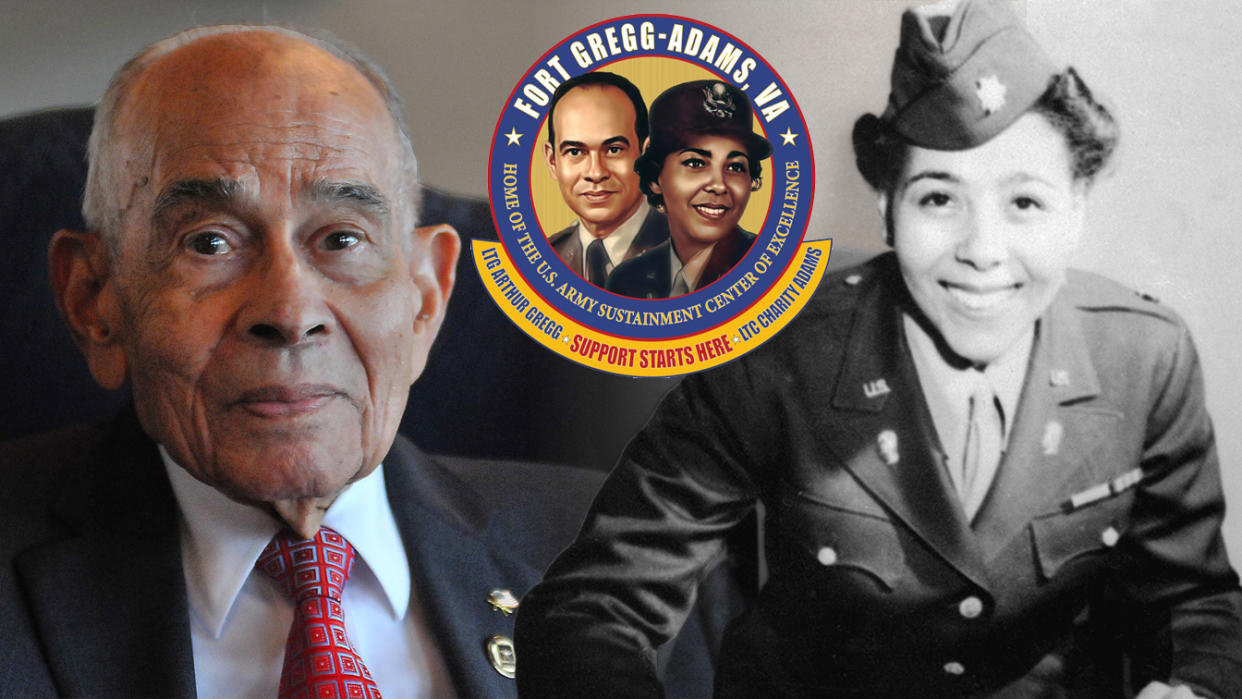

Fort Lee, an Army base in Virginia named after a Confederate general, was renamed on Thursday as Fort Gregg-Adams to honor Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams, two Black officers who served in the U.S. Army.

At 94 years old, Gregg is the only living person in the Army’s history to have a base named after him, according to the U.S. Army. Gregg gave more than three decades of his life to the military and became a three-star general during his service.

“I’m grateful to all. I hope that this community will look with pride on the name Fort Gregg-Adams and that the name will instill pride in every soldier entering our mighty gates,” Gregg said during the redesignation ceremony on Thursday.

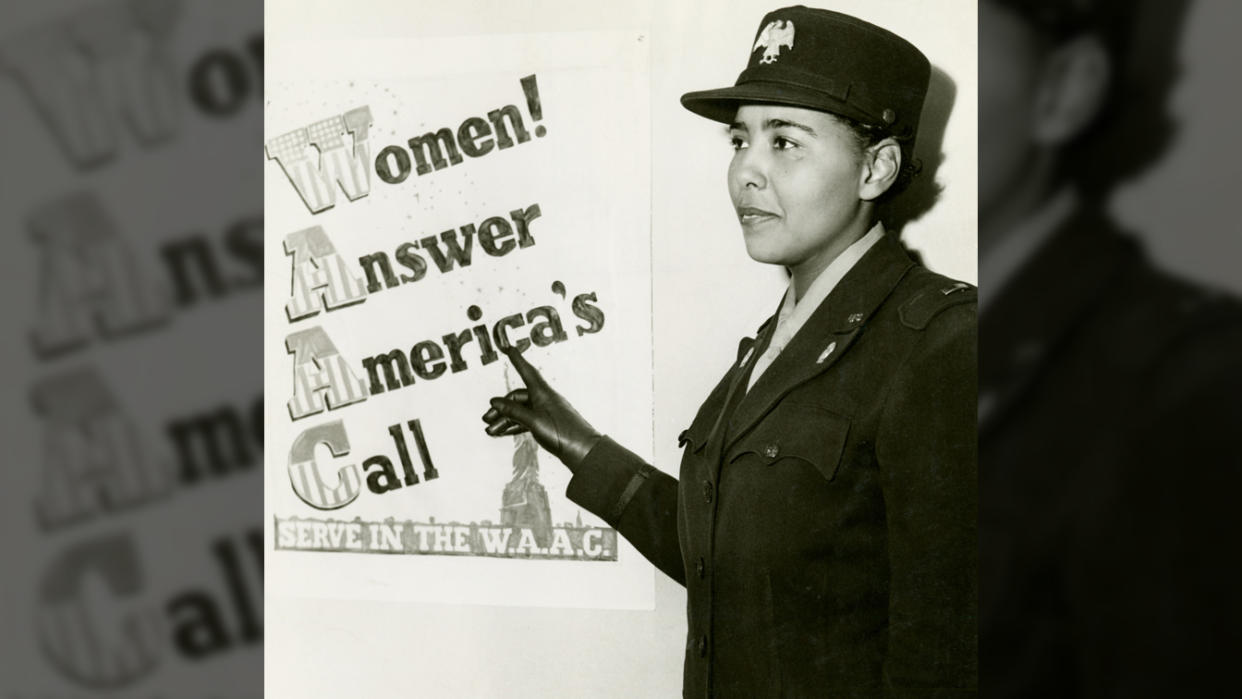

The base will be jointly named for Adams, who was the first Black officer in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (later the Women’s Army Corps).

“We are deeply honored to have Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams as the new namesakes for our installation,” Maj. Gen. Mark Simerly, senior commander of Fort Lee, said in a statement.

The fort is one of nine Army installations that will be renamed this year.

“Right now, some of these names represent people who don’t represent American values and people who fought to preserve the institution of slavery,” Raff Donelson, an associate professor at the Chicago-Kent College of Law, told Yahoo News.

In 2021, Congress created the Naming Commission under the National Defense Authorization Act, following the civil unrest after the murder of George Floyd. Then-President Donald Trump initially vetoed the legislation.

The act “includes provisions that fail to respect our veterans and our military’s history,” Trump said in a veto message to Congress in December 2020. “From these facilities, we have won two World Wars. I have been clear in my opposition to politically motivated attempts like this to wash away history and to dishonor the immense progress our country has fought for in realizing our founding principles.”

Despite Trump’s opposition, Congress overrode his veto and created a commission of eight individuals who were tasked with recommending the removal of all Defense Department property that commemorated people who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Kori Schake, a member of the naming commission and the director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, told Yahoo News that the commission found over 10,000 items that fit the requirements for removal.

“It’s the legacy of slavery,” Schake said. “Defense Department swimming pools, apartment buildings, streets and other properties named for people who voluntarily served in the Confederacy.”

However, Schake says the commission couldn’t prioritize all 10,000 items because it was on a strict deadline of about 18 months to complete its recommendations.

“We focused on the Army bases and two Navy ships, and then also released a report explaining our findings and a list of about 100 particularly well-qualified and vetted people that we would recommend that they consider [as replacements],” Schake said.

The final report recommended name changes that were estimated to cost over $60 million, including the renaming of the nine Army installations, which was estimated to cost $21 million.

But recently, the cost to rename the nine Army bases has increased to $39 million. “The Army is trying to solve the funding piece, and we’re trying to solve it internally,” Lt. Gen. Kevin Vereen told a House Appropriations Committee at a budget hearing, American Military News reported. “We’ll take the funds from the [Defense] Department.”

Though the cost has raised some concerns, experts say these changes are invaluable.

“It may cost $40 million to do the renaming just of the bases and things related to the bases, [but] that is a drop in the bucket of the Department of Defense’s budget,” Donelson said. “While $40 million may seem like a lot, $40 million out of the $842 billion that the Department of Defense recently requested for its budget is far less than 1%. It’s far less than a half percent. It’s only 1,000th of a percent.”

The nine bases that will receive new names are Forts A.P. Hill, Bragg, Benning, Gordon, Hood, Lee, Pickett, Polk and Rucker.

“Many of the bases were named after traitors, Confederate military leaders who betrayed our country, betrayed the Constitution and had no right to have any military base named after them,” Domingo Garcia, national president of the League of United Latin American Citizens, told Yahoo News.

Now experts say the bases will be named after American heroes. The naming commission held hearings across the country for the public to recommend new names for the bases.

“I addressed the commission and pushed for the renaming of Fort Hood for Gen. Cavazos, the first four-star Latino general, a hero of the Korean War, decorated veteran, and who had served as a commander at Fort Hood,” Garcia said.

The commission accepted the recommendation, and Fort Hood will be renamed on May 9.

As buildings and monuments across the country lose their ties to the Confederacy, experts say the military is one step closer to reflecting an America “that includes the rich diversity of the people who serve in our armies and our military, and those who have fought and served this country in the past,” Garcia said.

But according to a 2020 Washington Post poll, 52% of Americans are against removing public statues that honor Confederate generals. Similarly, a Morning Consult/Politico poll of registered voters in July 2021 found that 51% of voters believe such statues should not be removed.

Yet the American landscape is changing; 48 Confederate symbols were removed, renamed or relocated in 2022, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). In addition, three Army bases — Forts Lee and Pickett in Virginia and Fort Rucker in Alabama — have been renamed.

“It is embarrassing that our country ever had military bases named after men who waged war against the United States to maintain slavery and white supremacy,” Rivka Maizlish, senior research analyst for the SPLC’s Intelligence Project, told Yahoo News.

“Service men and women of color should not have to endure these racist symbols, and no American should be asked to serve a country that celebrates treason, slavery and white supremacy.”

The naming commission has set a January 2024 deadline for the military to remove all recommended items that commemorate the Confederacy.

“Why must it take so long to do what’s right? There is no cause for further delay. The time for swift action is now,” Maizlish said.