Remembering cyberspace’s most-wanted hacker and his unlikely capture in Raleigh in 1995

In 1995, Raleigh woke to the spellbinding news that an FBI fugitive, a mad-scientist computer hacker gifted at burrowing into secret files, had been captured in a nondescript apartment off Duraleigh Road — along with a confiscated trove of electronics, maps and a Denny’s napkin.

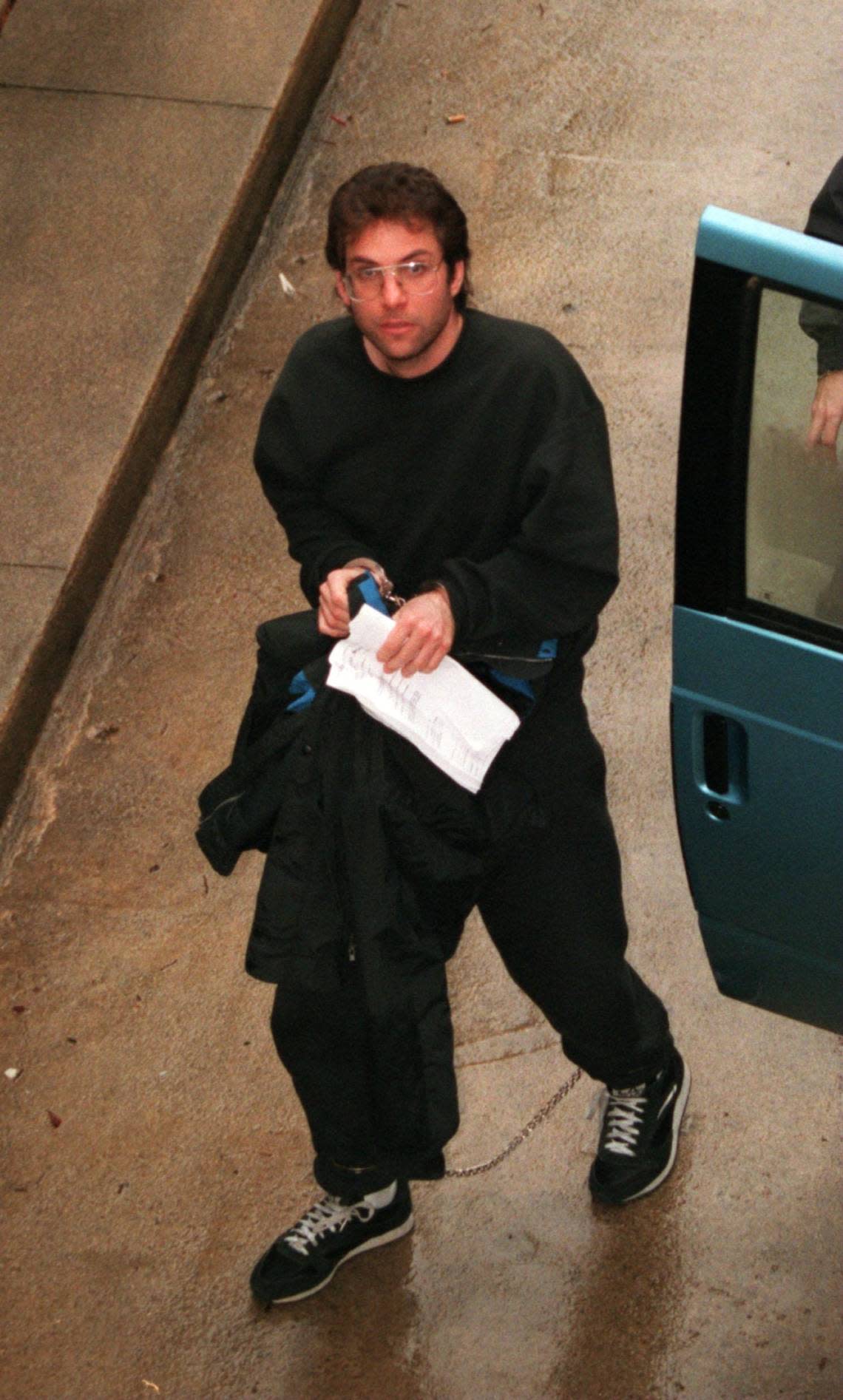

When the city first glimpsed Kevin Mitnick, then 31, he was unshaven and bespectacled in a black sweatsuit, his hair in a ponytail and his hands in shackles, heading into a Wake County jail cell — end of the road for a cyber-pirate known as “The Condor.”

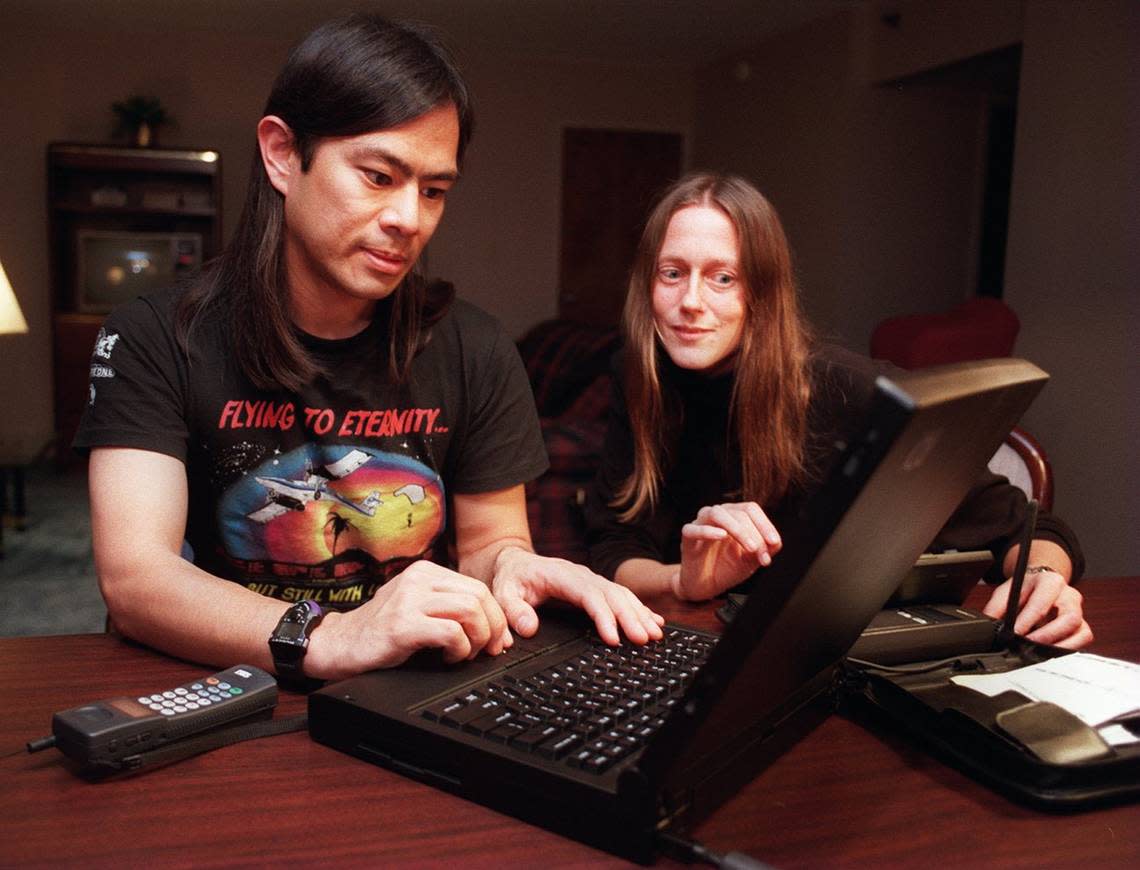

But over the next year, a sprawling adventure story would unfold, pitting the shy, unassuming Mitnick against Tsutomu Shimomura, the super-brained physicist and security expert who tracked the hacker down out of spite for being one of his victims.

And though that story would evolve, showing Mitnick to be less a villain out for money than a cutting-edge rogue motivated by a hacking challenge, he would serve nearly five years in prison.

A ‘white-hat hacker’

By the time he died last week at 59, the man formerly known as “Cyberspace’s Most Wanted” was working as a “white-hat hacker,” getting paid to do what once made him a criminal. Some even called him a hero.

“They have made me out to be John Dillinger or a desperado,” he once told The Guardian, “but I’m just an excellent prankster. I have never profited from it.”

A native of Southern California, Mitnick launched his hacker’s life at age 12, when he figured out how to rejig the Los Angeles bus passes so he could ride for free.

I just recovered the contents of an old safe deposit box from the states controllers office.. and what do I find? The ORIGINAL RTD bus drivers punch and blank transfers I used when I was 12 years old to ride the LA bus system for free!! pic.twitter.com/eyOpsBid2H

— Kevin Mitnick (@kevinmitnick) February 8, 2019

He ran seriously afoul of government investigators in his 20s when he swiped more than $1 million in software from Digital Equipment Corp, then hacked into Pacific Bell computers while still on probation — making himself into a wanted man. Along the way he would penetrate security at IBM, Nokia, Motorola ...

He cloned cell phones, stole passwords, broke into emails, called technicians posing as supervisors, rerouted private calls to ring at payphones so he could hack the numbers. He got numbers to tens of thousands of credit card accounts but, to anyone’s knowledge, never used them.

A chase with federal agents

But friends at the time reported that he used computers to woo the woman who would become his wife, and that he was a confused kid who loved the ocean and a pet poodle. Years later, Mitnick would brag of hacking into a McDonalds computer and telling people in the drive-through line they were the day’s 100th customer and their meal would be free.

Even with federal agents tying themselves in knots trying to find him, he kept up a playful chase, once buying a box of Winchell’s donuts and leaving them in the refrigerator for the FBI to find, complete with a note.

“They didn’t eat one of them,” he told Cybercrime Magazine.

But by most accounts, his undoing came while breaking into Shimomura’s personal emails in San Diego, inspiring the future Nobel laureate to help the FBI track Mitnick down in a fit of cyber-sleuthing, staking out his Raleigh apartment.

Several days after the break-in, Mitnick allegedly left voice-mail taunts:

“My technique is the best,” he said in one, employing a British accent. “My style is much better. Don’t you know who I am? Me and my friends, we’ll kill you.”

He used a Japanese accent for the second: “Your technique is no good.”

Then in February of 1995, when Mitnick walked into Raleigh’s federal courtroom, he scanned all the eyeballs in the room until he found Shimomura’s, pausing to glare at the man who bested him.

But for Raleigh, the greatest mystery remains why Mitnick landed in North Carolina’s capital rather than Cairo or Istanbul or Havana — someplace that better fit a life of intrigue.

Lured to Raleigh by magazines, Monopoly

At the time, he told a rental-car clerk that he’d been lured by all the mid-90s magazine covers that touted Raleigh as the best place to live, and sure enough, inside his apartment, agents found 44 job applications, a stack of business cards and a book titled, “The 100 Best Companies to Work for in America.”

Then in 2018, he told WRAL that he’d taken inspiration from a Monopoly board, and being fond of the green streets, chose to follow North Carolina Avenue.

Long before his death, he collected fans outraged at the time he spent behind bars without a trial, many of whom called the charges exaggerated and inspired by zeal to prosecute what was, at the time, a poorly understood crime. Shimomura would experience a similar shift in sympathy, where those same fans asked why he’d been so involved in a federal investigation.

“Kevin attracted attention and support from unlikely sources,” his family wrote in his obituary. “The bus driver who saw young Kevin memorize the bus schedules, punch cards and punch tool systems so he could ride the buses all day for free testified as a character witness for Kevin during his federal trial. The federal prosecutor offered his testimony that Kevin never tried to take one dime from any of his ‘victims.’ The probation officer assigned to monitor Kevin after prison gave Kevin permission to write his first book on a laptop when he was not yet supposed to have access to computers. “

In the end, Mitnick would joke online about his early escapades like men his age who laugh about their own juvenile delinquency, and the Internet is loaded with his tips for avoiding foiling online predators.

The world could hardly cross through the internet better armed than with caution from an old cyber-fox, eye still twinkling at the memory of his exploits, who knows the back door out of every trap.