Reggie Warford is a Kentucky basketball legend. Two UK greats reflect on his legacy.

It will be a bittersweet occasion in the home of Kentucky basketball on Wednesday night.

There will be joy that the legacy of Reggie Warford is being remembered. There will be sadness that the trailblazing Wildcat is no longer here to see that legacy celebrated.

UK will host Florida A&M in Rupp Arena in the second edition of the Unity Series, a five-year partnership between the Wildcats’ program and the Southwestern Athletic Conference, which consists of historically Black colleges and universities. The goal of the series — in which the Cats will face a SWAC team each season — is to raise awareness of the missions of HBCUs.

A goal of this specific installment will be to honor the achievements of a special UK player who changed the trajectory of a program with the self-proclaimed “greatest tradition in the history of college basketball.”

If it weren’t for Warford, that tradition might not be quite as rich.

A standout high school player from tiny Drakesboro in Muhlenberg County, Warford came to the University of Kentucky in 1972, a time when there were no Black players on the Wildcats’ basketball team. Tom Payne had become UK’s first Black player two years earlier, but he played only one season of varsity ball before leaving Lexington.

Warford would ultimately become the first Black player to stay at UK for four seasons and the first to graduate from the university. Along the way — and amid hardships — he laid the foundation for change and played a large role in the transition to a new era of Kentucky basketball.

That legacy will be celebrated Wednesday night.

“Certainly, if there’s a guy who deserves to be honored, Reggie would be at the top of the list for a lot of us,” said Jack Givens, the most outstanding player of UK’s national title run in 1978.

“He would have been thrilled. Excited about it. Humbled to the point that he wouldn’t feel like he was deserving of it,” said James Lee, one of the top Wildcats on that championship team.

Those who knew Warford — or simply know of him — will surely say he’s more than deserving of any such honor.

Warford passed away in May at age 67 after battling numerous health issues in recent years.

His story will always have a place in whatever history is written of UK basketball.

Givens and Lee were both high schoolers in Lexington when Warford came to town, the first recruit for new head coach Joe B. Hall and the only Black player on that Wildcats’ team.

It’s fair to wonder if Givens and Lee — two integral parts of the Cats’ championship team six years later — would have ended up at UK if not for Warford’s presence. And, without them, it’s difficult to imagine Kentucky cutting down those nets, what ended up being the program’s lone national title between 1958 and 1996.

“As a kid, I never followed Kentucky basketball,” Givens told the Herald-Leader last week. “I never thought — as a kid — that I would have an opportunity to even go to school there, let alone play basketball there, because of the racial situation. …

“So to be able to play basketball there was never something that entered my mind until my high school years. And Reggie was there at that time. … Yeah, he figured into it prominently — my decision to go to the University of Kentucky.”

Givens said Warford was among those who reached out directly to him during the recruiting process, when he was a standout player and the state’s Mr. Basketball at Bryan Station.

Lee, a star forward at rival Henry Clay, said the same, recalling that Warford called him multiple times to sell the UK program and promote the change he was leading from within.

“That was nice of him to even reach out to me, and to talk about Kentucky basketball and how the program is progressing to get Black athletes there, and that he would love to have me on board,” Lee told the Herald-Leader on Monday.

Reggie Warford’s decision

Warford was originally committed to Austin Peay before switching that pledge to UK following the arrival of Hall, who was replacing Adolph Rupp as head coach. Leonard Hamilton, who would later become Hall’s lead assistant with the Wildcats — and go on to become a successful head coach himself — was on the Austin Peay staff at that time. And the story goes that Hamilton actually told Warford that he thought he had the personality and the strength to endure what he might face at Kentucky.

“For him to make that decision was huge, at that time,” Givens said.

Those who knew Warford best often describe him as humble but also confident. Soft-spoken, but a young man who held deep convictions and possessed a keen sense of justice, whatever the situation.

Lee said that Warford had relayed some difficult stories to him regarding his start at UK, especially that first season.

“There were tough times,” he said.

One night at the beginning of Warford’s freshman year, Lee says, the team’s only Black player was having dinner and a man passed him a card. “Welcome to Klan country,” it read.

“He just kind of smiled at him and said, ‘Oh well.’ That’s just the way he was,” Lee said. “It’s kind of hard to describe him. He was just the epitome of a young man that was strong in his beliefs, strong in which direction he was going — and nobody was going to deny him of that direction.”

Warford was still just 17 years old when he began his freshman year of college.

“A lot of guys — myself included, maybe — wouldn’t have been able to deal with some of the things he had to deal with his first year there,” Givens said. “I couldn’t imagine. He was absolutely the right guy.”

Amid the abuse from a certain segment of people who didn’t want him there — while also dealing with the stress that comes from being a freshman basketball player at a place like Kentucky — Warford didn’t waver. And he actively recruited other Black players to join him in Lexington.

The following season saw the addition of Merion Haskins and Larry Johnson. The season after that, hometown heroes Givens and Lee arrived on campus. And prior to Warford’s senior year, Truman Claytor and Dwane Casey signed with the Wildcats.

Those who followed Warford had a “big brother” — as Givens has called him — waiting for them on campus, someone who had been through it on his own, someone who could help the new guys navigate what was to come next.

“The first thing about Reggie is he did not hold back on sharing his opinion on how we should approach things. Givens said. “So, yeah, he was that kind of figure to us. But he was also the kind of guy who was very confident about himself and about his talent. He heard what people said — if there was anything said — but he was not affected by it. It didn’t change his life or how he lived. And that was a great example for us younger guys coming in. He brought us along.

“He was a mentor, even when we were all going through some of the same things, because he was a little older. And he had experience and had experienced things that we hadn’t. So, yeah, absolutely, he was a big brother to us. And he was a protector, too. He could say anything he wanted to about us, but if somebody outside of us said something, he was ready to go to war for us. That’s just kind of how he was.”

When told of Givens’ “big brother” remark, Lee took it a step further.

“He was a father,” he said. “He was the little godfather at UK. How can you speak of him? He was a gifted young man at a perfect time to fit at UK. He was soft-spoken. He was firm. He stood his ground. And he helped us. You couldn’t ask for a better friend, a better teammate, a better guy to be around than Reggie. Good conversations. He played the piano. He sang. He was just a gifted young man.”

Warford’s legacy at UK

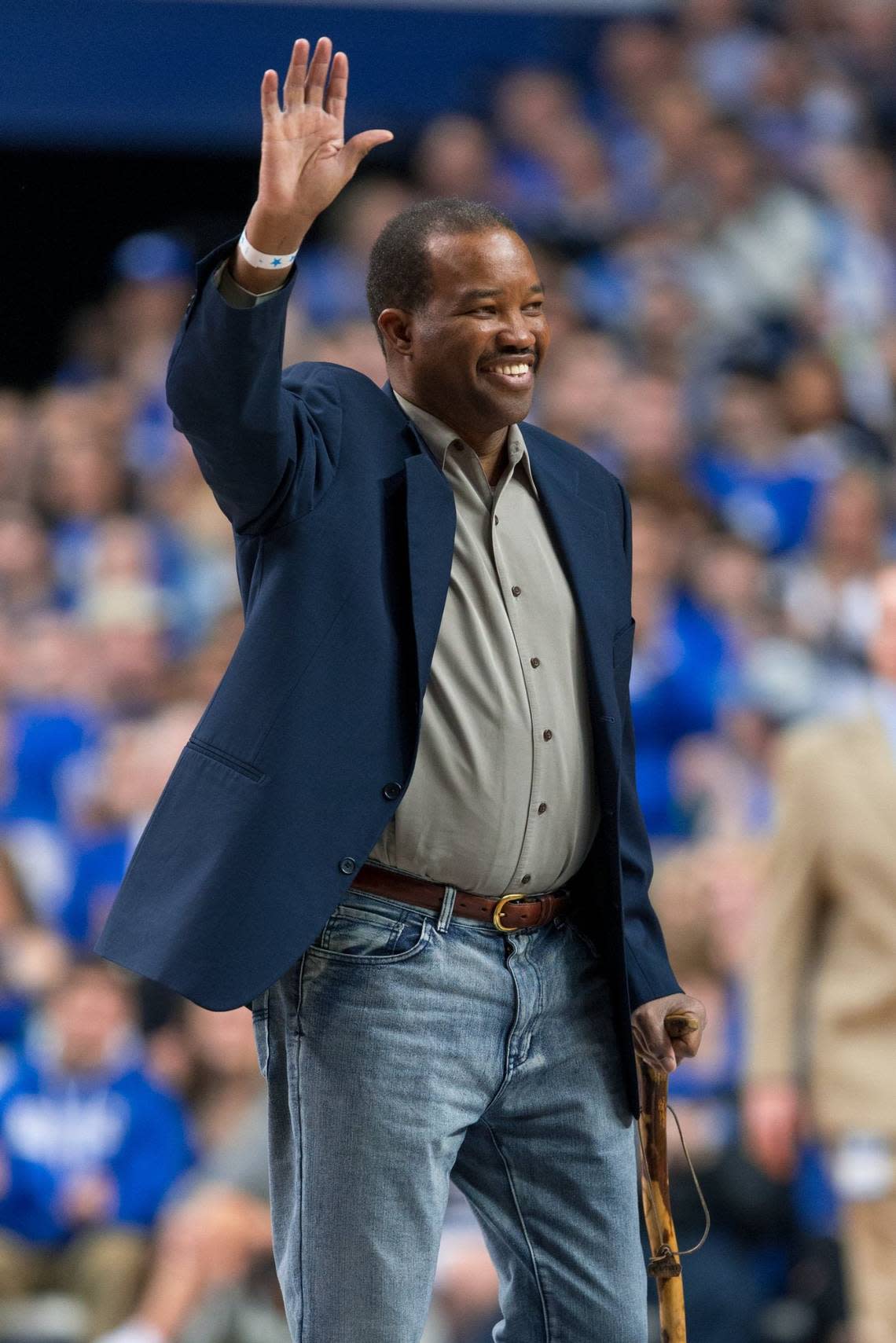

Lee lamented this week that Warford didn’t get more recognition while he was still alive. It would have meant a lot to him to be in front of the UK fans and feel the appreciation, he said.

While that certainly became true more recently, it wasn’t always the case.

“For most of Reggie’s life, I would say that he would want to try to avoid this kind of recognition, because he was not a guy who sought out that kind of recognition,” Givens said. “But in the latter years of Reggie’s life, I think — the older he got — the more he realized how truly important he was for Kentucky basketball. I think in the latter years of his life — and I include the success that James and I had at Kentucky, along with Merion and Larry Johnson — the early guys who had an opportunity to either play with Reggie or got to know him real well over their careers here at UK — the older he got the more he realized his position with Kentucky basketball and the advancement of African-American players there.

“I think he would be very, very proud to stand there. To be recognized in this way. It would definitely bring him to tears.”

Warford was a humble man, but, as Givens says, he also embraced the importance he had on UK basketball as he grew in years.

In 2018, Warford sat down with interviewer Dennis Emery for a chapter in an oral history project related to the Kentucky program.

At one point in that interview — a must-watch for any UK basketball fan, by the way — Warford beamed with pride when recounting his journey from being the team’s only Black player to, a few years later, checking into a game and realizing that it was the first time five Black players had represented the Wildcats on the court at the same time.

He said that progress was a tribute to Hall, but he also claimed his rightful place in that moment.

“This is a part — and I don’t say Kentucky’s history, because I’m part of Kentucky — it’s a part of our history, that people may say, ‘Well, why do you need to bring it up now?’ If you don’t remember how you got there, you’re not going to understand where you’re going,” Warford said. “And we got there because a poor kid from Drakesboro, Kentucky, came to the University of Kentucky. And brought in Larry Johnson and Merion Haskins. That brought in James Lee and Jack Givens. That brought in Lavon Williams and Truman Claytor. That brought in …

“That’s the process. Would it have happened? Somebody would’ve done it. But nobody else did. Somebody could’ve done it. Nobody stepped up. But I did. And remember me however you want to, but I came here with that. And that’s part of my heritage.”

Givens said he didn’t realize the importance in the moment, but Warford pointed out to him that they had been part of UK’s first all-Black lineup in the locker room after the game.

“It was a huge steppingstone that, you know, the program had advanced to that,” Givens said. “We discussed that. And it was a huge, huge moment, when that happened.”

Givens, undoubtedly one of UK’s most-celebrated players, hopes Warford’s role in Kentucky basketball is not forgotten. He hopes occasions like Wednesday night will lead to more people learning of his former teammate’s story. That goes for the current Wildcats, as well.

“A lot of people don’t understand,” he said. “A lot of the young players don’t understand. And can’t understand, because it’s so different now than it was. But, I just hope — I know he’s been given a lot of credit for the way things are — but I hope people truly understand what a difficult, difficult decision it was for Reggie. And how difficult it was for him the first year. And I hope people fully appreciate what he did by making the decision to come to the University of Kentucky. …

“I would love for them to look him up and to read about him and to hear some of the things he said, because there are lessons in there that they won’t learn any other way.”

Warford scored 206 career points over four years for the Wildcats, with 182 of those coming during his senior season. His name won’t be found too often in the UK record book, but his impact on the program goes far beyond any box score.

That interview four years ago for the UK oral history project ended with the following question: “How do you want people to remember you at the University of Kentucky?”

It evoked an emotional reaction.

“Well, I didn’t see that one coming,” Warford says, pausing to gather himself and his thoughts.

“It’s tough to go back, you know, 40 years now,” he continued. “I’d like them to remember and acknowledge that that was my start. That, yeah, there was a guy named Reggie Warford that came to UK and brought other guys with him. And did things the right way when he was here. Was a good teammate. Loved Kentucky basketball. And really appreciated the chance to get to show what I could do. So, that would be nice.”

Wednesday

Florida A&M at No. 13 Kentucky

What: Unity Series

When: 7 p.m.

TV: SEC Network

Radio: WLAP-AM 630, WBUL-FM 98.1

Records: Florida A&M 2-7, Kentucky 7-3

Series: Kentucky leads 1-0.

Last meeting: Kentucky won 96-76 on March 19, 2004, in the NCAA Tournament in Columbus, Ohio.

Reggie Warford remembered as ‘a proud man,’ ‘true friend and brother’

Reggie Warford, ‘patriarch’ of integration for Kentucky basketball, dies at 67

Joe B. Hall remembered as ‘a real competitor,’ Breakfast Club regular

‘I was dreading this day.’ Joe B. Hall remembered by his Kentucky Wildcats family.

Kentucky legend Jack Givens is the Cats’ new radio analyst. ‘For the fans, he’s family.’