Recycling groups say the enemy is plastic. Will NY lawmakers act to combat waste 'crisis'?

Environmental advocates are pressing New York lawmakers to confront the villain they say is behind the state’s low recycling rates and the garbage piling up in landfills and incinerators.

Plastics.

In the final weeks of the legislative session, lawmakers will take up several measures aimed at keeping plastics out of the waste stream.

One would create greater incentives for recycling plastic, glass and aluminum by doubling the nickel deposit for beer, soda and water containers while adding wine, liquor and non-carbonated beverages like teas and sports drinks to the list of containers with a deposit.

Another would increase the 3.5-cent handling fee bottle redemption centers currently receive for recycling those containers, a move advocates say will reduce litter and improve the recycling rate for plastic, glass, and aluminum.

But the centerpiece of the effort — and the one getting the most pushback — is an attempt to reframe the recycling debate by making companies who do business in New York stop producing so much plastic.

It would largely be aimed at keeping so-called single-use plastics (straws, utensils, cups, plates and the like) from ending up in landfills and incinerators.

Known as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), it would force companies who want to do business in New York to reduce paper and plastic from their packaging over time. New York would join four other states — Maine, California, Oregon and Colorado — with similar laws.

It’s an idea born out of a sobering recognition that 40 years after blue bins became a weekly curbside fixture in cities and towns across New York, the state’s recycling efforts are failing to live up to their early promise.

“Plastic recycling has been an abysmal failure,” said Judith Enck, the president of the advocacy group Beyond Plastics and the retired heard of the New York and New Jersey region for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Trash: NY's recycling programs down in the dumps while more trash heads to landfills

'Crisis on the horizon:' Is reducing plastics the answer?

Just 5% or 6% of plastics get recycled, according to a 2022 Beyond Plastics report. The rest ends up in landfills and incinerators, a crushing burden for towns across the state, from Seneca Falls to Peekskill, that are home to those facilities.

“There’s a serious crisis on the horizon, where all the landfills are scheduled to be closed in the next couple of decades,” said Blair Horner, the executive director of the New York Public Interest Research Group. “And what are you gonna do with all that stuff? You have to start grappling with these issues. And unfortunately, so far that hasn’t happened.”

The state’s overall recycling rate — for paper, plastic and food — has been stuck around 18% for decades, below the national average of 32%. More than 80% of the state’s 18 million tons of waste goes to landfills and incinerators or is shipped out of state.

Businesses that will be impacted are fighting back.

Opposing the EPR bill is the American Chemistry Council, the high-powered lobbying group that represents plastic producers.

The council dismisses the claim that plastics recycling has been a failure, saying it works well when plastic gets into the bin.

While supportive of efforts to reduce the flow of plastics to landfills and incinerators, the council is unhappy with the current version of the EPR bill, predicting it could end up costing consumers nearly $6 billion more in costs over the next five years.

“Unfortunately, this proposal misses the mark and will have unintended consequences by eliminating packaging that plays a critical role in keeping people safe and reducing waste,” said Ross Eisenberg, the president of America’s Plastic Makers, a division of the council. “It also limits the capacity for recycling, cutting off innovative solutions that would allow us to keep more plastics out of landfills.”

The state’s farmers are also against it, saying the measure will add to their costs for packaging milk, wine and food.

“As we have said many times, when state lawmakers make it more expensive to produce food in this state, they drive away local food and jobs,” said Steve Ammerman of the New York Farm Bureau.

When it comes to money, county recycling is a losing game

The measures under consideration grew out of two days legislative hearings in October that drew a broad array of voices on the recycling debate.

Among them were the heads of county recycling programs, who’ve been struggling amid a plunging volume of recyclables and surging costs.

A 2023 report by the state Department of Environmental Conservation pinned much of the blame on China’s decision to limit the amount of paper and plastic it takes in from the U.S., which impacted the recyclables market.

Some recycling programs are considering abandoning curbside recycling.

Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger heads the climate action committee for the New York Association of Counties, which for the past two years has passed a resolution supporting EPR.

“While it’s not always easy to get agreement among the 62 counties, this is an issue around which all counties have coalesced and support, bridging typical Democratic-Republican divides, urban-rural divides,” Metzger said during a press conference last week. “Municipal recycling programs are under serious financial stress. They’re on the receiving end of materials that cannot effectively be recycled and the costs of collecting and processing recycling have increased.”

Onondaga County, for instance, has invested $5.6 million in curbside recycling since 2019 but the amounts they take in are declining.

The EPR measure would force companies to reduce plastic packaging by 50% over 12 years.

After 12 years, all packaging — plastic, glass, cardboard, paper and metal — must meet a recycling rate of 70%.

It prohibits the use of toxic chemicals like PFAS and vinyl chloride and heavy metals in packaging.

Enck said the bill addresses many of the challenges to recycling plastic, which can include thousands of different chemicals, in many different colors. For instance, she said, a laundry detergent container might not be able to be recycled with a ketchup bottle because of their different chemical makeup.

“That’s why plastics recycling is so low and the plastics industry knows this,” Enck said. “But they’ve spent 30 years advertising, telling us ‘Oh, don’t worry about all your plastics, just throw it in a recycling bin.’ Well, people know more and more that’s not real.”

The hearings were led by Democrats Pete Harckham, the chairman of the Senate environmental committee and his Assembly counterpart, Deborah Glick. “It’s hard to avoid the onslaught of information about the harms plastics cause,” Harckham said.

The measure has the backing of Gov. Kathy Hochul, who’s pitched the idea before.

Who's fighting for better recycling options in NY?

This wouldn’t be the first time the state has forced companies to pick up the tab for what they put into the waste stream.

In recent years, the state has forced manufacturers of rechargeable batteries, paints and other products to pay for their recycling.

The movement has attracted a broad array of allies.

Among them are environmental justice groups who live in areas that are home to landfills and incinerators.

Courtney Willams’ group, the Westchester Alliance for Sustainable Solutions, is fighting a permit extension for Westchester County’s lone incinerator.

She says air pollution from plastics and other material is creating health problems for nearby communities.

“We’re the communities that don’t have the resources to fight back,” Williams said. “They’re not putting this in Chappaqua or Scarsdale or Pound Ridge. They’re putting it in Peekskill and Yonkers and places like that.”

Advocate groups in the Finger Lakes opposed to the expansion of the Seneca Meadows landfill, one of the state’s largest, made a similar argument in their bid to get the state Department of Environmental Conservation to deny its owners a permit.

Landfill: How an upstate town famous for a Christmas classic film became NY's dumping ground

The EPR legislation is being considered alongside several proposals to update the state’s 40-year-old Bottle Bill, as part of a wide-ranging review of the state’s waste problems.

Some of the loudest calls for change have come from the owners of bottle redemption centers who’ve seen their ranks thinned in recent years.

Inflation and an increase to the state’s minimum wage have led to layoffs and shutdowns for businesses that rely on large volumes of recyclables to make their money.

In 2018, the industry counted about 1,100 businesses but in recent years is down to around 750, according to Peter Sidote, the owner of a Long Island redemption center and a leader in the Empire State Redemption Association.

“They’re holding their head under water and they’re asking them to breathe,” said Sidote. “We’ve been asking for this for a couple of years now and we keep on getting sidetracked by the legislature.”

A pending bill would increase their handling fee to 6 cents per container.

“The redemption centers are a sympathetic bunch, small business owners who provide an important service,” Horner, of the New York Public Interest Research Group, said. “From my conversations with lawmakers people want to deal with that but it’s just a question of how.”

Cardboard tombstones and the Grim Reaper

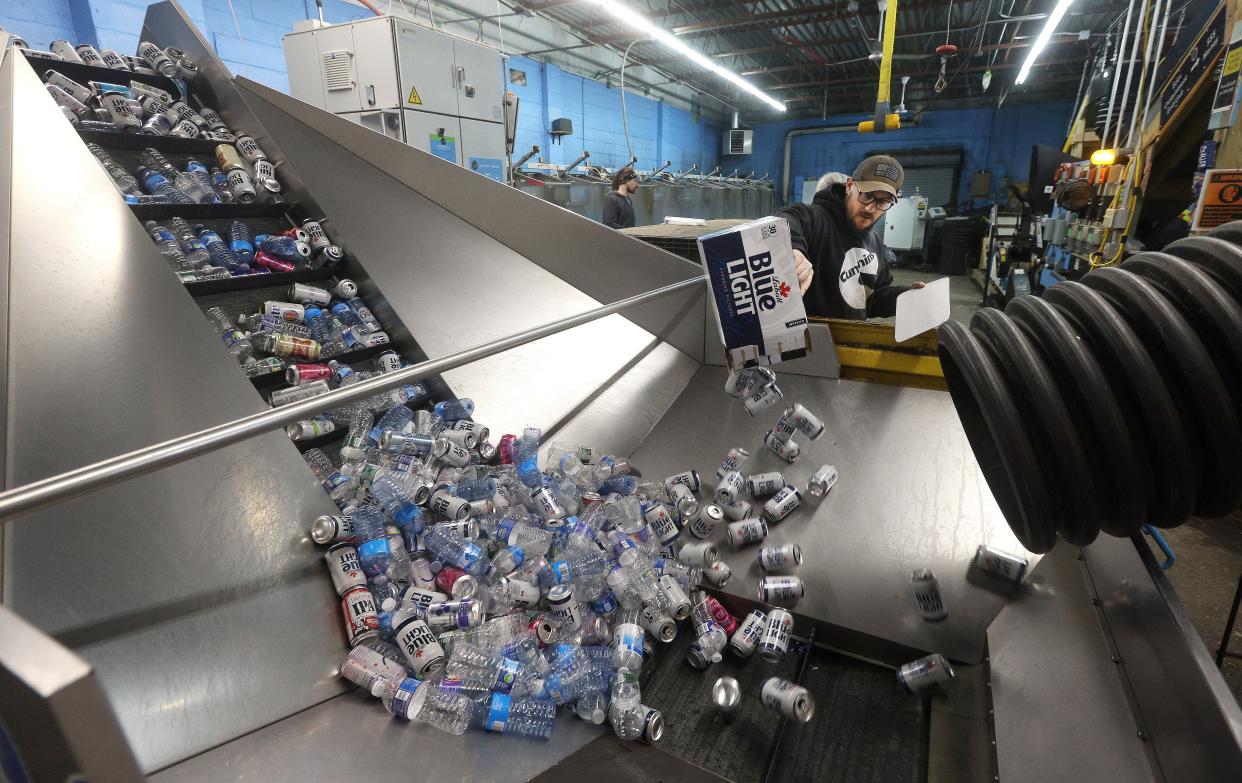

Pete Baker runs Can Bottle Return in Hamburg near Buffalo. One of the state’s busiest, the business recycles some 750,000 containers per week and contracts to pick up cans and bottles after Buffalo Bills home games.

“While the Assembly and the Senate sit on their hands and wait for a piece of legislation that satisfies all parties involved, the entire system of bottle redemption is crumbling under their feet and will accelerate within the next eight months,” Baker said. “Rural areas are getting hit first, and now we are seeing it in even high demand areas. Soon returning your cans and bottles will be such a burden in New York State that consumers will give up and more containers will not get redeemed, recycled, and reused properly and end up as general litter, in waterways, oceans, or in landfills lasting thousands of years.”

On Monday, several center owners turned out for a rally at the state Capitol where they displayed cardboard tombstones with the names of centers that have closed in recent months. Jade Eddy, the owner of a Queensbury redemption center, cloaked herself all in black to portray the Grim Reaper.

They were joined by several nonprofits who’ve turned to bottle redemption as their primary fundraising tool.

State officials and environmental groups appear united in their opinion that the Bottle Bill has successfully kept litter off streets and flowing into the recycling stream. It’s easier to recycle a clear plastic bottle than a colored detergent container, Beyond Plastics notes.

Canners: They gather up cans and bottles on NY streets for recycling. And they could use a raise

The state’s redemption rate for beverage containers has averaged around 64% in recent years, significantly higher than the 24% rate for states that do not require a deposit.

The state hit a record high 70% redemption rate in 2021, delivering $127 million to the state budget. Some of that funding could go to assist redemption centers to help them outfit their operations with technology that would speed counting and sorting.

A state DEC waste report issued last year noted that in 2020, some 8.6 billion containers were sold and 5.5 billion redeemed in New York, resulting in 241,505 tons of plastic, glass and aluminum recycled.

But Sidote and other say the rates could be even higher if the state makes other types of containers like non-carbonated sports drinks eligible for a deposit.

Opposing groups like the Business Council of New York State say the measure is unnecessary at a time when the state’s bottle redemption rate hit an all-time high. Coupled with EPR, the program will lead to more costs for the impacted businesses, the council says.

Ken Pokalsky, the council’s vice president, says the bottle redemption centers will be taking in recyclables that could be going to municipal recycling programs.

“Why impose more direct costs on consumers and divert more material from the broader material recovery program?,” said Pokalsky.

EPR’s supporters say they’ve rounded up overwhelming support in the Senate and Assembly and are hoping for a full vote in the coming days.

Last week, 27 environmental justice groups representing disadvantaged communities across the state sent a letter to Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie urging them to hold a vote on EPR.

The letter cited the toll that burned waste has taken on communities across the state — in Niagara Falls, Poughkeepsie, Peekskill, Long Island and elsewhere.

“Instead of mucking about for decades trying to regulate these toxic chemicals at incinerators, this bill will reduce these most harmful chemicals at the source, eliminating them from the packaging waste stream,” they write.

Tom Zambito covers energy, transportation and growth for the USA Today Network-New York. Reach him at Tzambito@lohud.com.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Recycling groups say plastic is the enemy. Will NY lawmakers act?