We will rebuild in EKy. Then we must ask why 100-year floods are happening so often.

At what point is a hundred-year flood not a hundred-year flood? At what point do we acknowledge the effects of climate change or that it exists? When streets in the UK melt under record heat waves? When our coastlines continue to chip away due to rising water levels? When we continue to see the frequency and severity of storms increase exponentially.

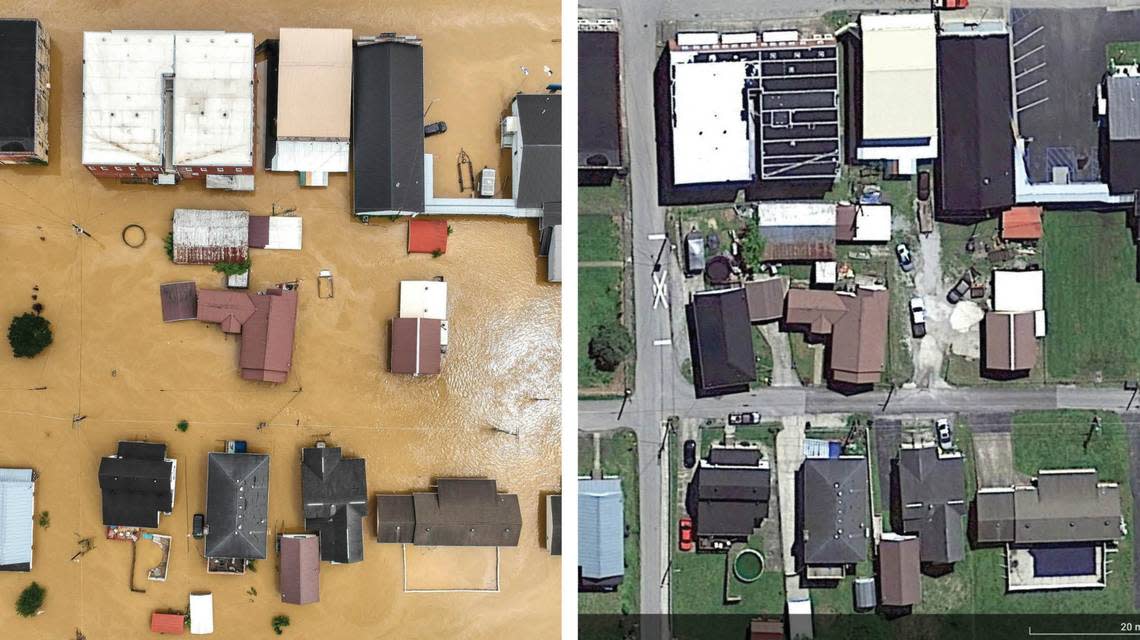

For me, it’s when my home, eastern Kentucky, experiences a hundred-year flood once a year as we sit idly by and accept this as our new normal as if there’s nothing we can do to change it. However, what happened in eastern Kentucky on the night of July 28, 2022, is nothing short of monumental. We are not strangers to the effects of flash flooding after heavy rainfalls. It’s something the region has battled for years. When our mountaintops are removed, there’s no place for the water to go, so it fills valleys and streams at a record pace faster than the banks can hold. And you’re left with homes sliding off mountains and water filling up living rooms.

I watched the events of July 28, 2022, unfold from my hillside home for the week while attending the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman, Kentucky. It’s a week every year that is magical and sacred to all that attend. But it was clear to me that this was, in fact, not normal. I watched as some of my dearest friends, not from the area, who lost their cars and spent all night watching the creek rise, wondering how they would get back home. But I was home; Knott County is where I grew up. And after the water recedes and the roads are cleared, items are packed, and all the workshop participants find their way back home, I, in fact, have nowhere to go to escape the inconveniences of no cell service, power, or water. But I watched the reactions of others as they wondered how long we would be stranded and took pictures as cars, tires, and garbage as it filled Troublesome Creek. I was already thinking about the months ahead. Would this one get the national attention we would need to get the help of FEMA, or would it take days and weeks like the catastrophic floods of years past? I assured them that the water would come up quickly, but it recedes in the same fashion. But I could tell they were witnessing nothing like they had ever seen before firsthand. And to be honest, I could tell this one was worse than what’s normal for us. Without contact with the outside world, I only later understood the enormity of what was happening all around us. The death toll continues to climb as we approach the 48-hour mark. Relief efforts are ramping up, and Appalachians are doing what Appalachians do, taking hits and helping neighbors.

I stand on the porch at Hindman. I pace and give hugs. I watch as everyone drives off. I’m left wondering where I will go next. My home in Jackson, Ky, 45 miles northwest of Hindman, is inaccessible—water is over the road, and it could be days before I’m able to get home. I know this from experience after being trapped at my house for 3 days in March of 2021 during a flood that brought record high water levels to Jackson. My grandma’s house in Hindman is a total loss and she’s staying with my mom. So, I decide to make my way to Hazard and assess the damage at the local bookstore I own downtown. This has become part of my routine since opening the bookstore in January of 2020 and experiencing two feet of water in the store a week after opening. I’m driving and thinking, thinking about these floods, one a year for the past three years and that’s just the ones that have had a direct impact on me. This doesn’t account for the countless others that are often localized in the region.

As the devastation hits social media, it’s scene after unbearable scene. Two of our most sacred spaces, Appalshop in Whitesburg, Ky, and the Hindman Settlement School in Hindman, Ky, have lost years of archives. Appalshop was founded in 1969 as the Appalachian Film Workshop. Originally a project of the U.S. government’s war on poverty, the people of eastern Kentucky have used Appalshop as a resource to preserve our rich cultural history. Years of pride and preservation. Years of work to preserve our existence. A history of people forgotten, and a time erased by most. A history we choose to document and preserve. We tell our story, not the narrative pushed by so many who visit from the outside. Is that what we have become, a place on the map that time and water can erase? With these documents gone, how will our children know the importance of who we are and what we have overcome? How do we move forward with a failing infrastructure that continues to become more and more fragile with every rising tide?

A hundred-year flood is a flood event that has a 1% chance of being equaled or exceeded within a year. The flooding that occurred in 2020, 2021, and 2022 could all fall in this category. But why here? Why now? What we are experiencing is unlike anything I have seen in eastern Kentucky. Beyond the need for explanation is a feeling of hopelessness for this region that I love. I see people who were just beginning to rebuild a life after the flood of 2021 knocked flat again this week. But I also see a community putting aside everything that divides us a nation to save lives. I have hope that we will persevere, will work to make a life in this place we call home; many of us who have been here for generations. We will do the work to save our precious archives, our only remaining connection to the past. After the cleanup, after we rebuild, we must address how climate change and extractive industries are already erasing our future.

Mandi Fugate Sheffel is a writer and the owner of Red Spotted Next, an indie bookstore in Hazard, KY.