Real Housewives of the French Revolution Tell All

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Above: An 1801 print captioned "The Orange, or, the Modern Judgment of Paris," represents (from left) Juliette Récamier, Joséphine Bonaparte, and Térézia Tallien in their slinky, norm shattering dresses.

We may be facing one of the great fashion revolutions of all time, entering a clothing era in which there are no boundaries between formal and informal, between masculine and feminine. Planetary climate change may forbid fast fashion and urge us toward radical revisions of what new means. Social media content creators may govern style changes instead of brand designers. If so, we can look back and take comfort in the knowledge that a fashion revolution has happened before. It was bold, glamorous, and scandalous, and led by three self-made media stars. It began during the worst violence of the French Revolution, in May 1794. Here’s how it happened.

THE VISIONARY PRISONER

The jailers in the Paris prison of La Force could not resist stripping Térézia Cabarrus naked. Along with all of France, they had heard rumors of her beauty. The French Revolution of 1789 had spiraled down by late 1793 into a regime its own leaders called the Terror. It was a dangerous time to be a French marquise, even one born a Spanish commoner, forced to marry into aristocracy at age 14, who had divorced her dissolute, abusive husband, the Marquis de Fontenay. The jailers gloated over the curves famously called “divine” by artists and connoisseurs. Then they hacked off her glorious jet black hair, tossed her a rough chemise undergarment, and locked her in a stinking cell. Straw rotted on the floor in a mixture of things unmentionable; moisture seeped through the cracks in the stone walls.

Térézia remained in the dark for 25 days. After her solitary confinement, she was roused every morning along with her fellow prisoners by the rattling of locks and keys, made to assemble and hear a list of who would be guillotined that day. The lists kept getting longer.

When Térézia arrived at the looming stone prison, she was wearing a conical edifice of bone stays, layered petticoats, and a three-piece silken gown of which the skirt fabric alone would have cost years of wages for a working woman. Her apparel was the sort of monarchic spectacle worn by Marie Antoinette (who had been arrested in August 1792 and guillotined in October 1793).

Térézia, however, had at the start wholeheartedly supported the Revolution, whose twisted course had landed her in a dungeon. At first, it was intended to topple the monarchy and correct the worst abuses of a decadent aristocracy. A newly elected government proclaimed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, to this day the fundamental statement of political equality. Alongside its momentous legal proclamations, the Revolution sought to reinvent daily life, going so far as to alter time itself with a new revolutionary calendar: the September 1792 declaration of the First French Republic became the start of Year 1.

Yet amid all these reforms the Revolution had not changed women’s clothing. Fashion may not seem very political, or maybe only a “weapon of the weak,” but it was political enough for women to be forbidden any deviation from the basic style rules that had governed their attire for centuries. Only a violent national trauma could shake society enough to permit a women’s clothing revolution. And only the personal experience of that trauma could cause Térézia, along with two other women, to lead fashion to a place it had never been before.

Térézia emerged from prison when the Terror ended in late July 1794 with no husband, no title, and no money. So did her new best friend, Rose de Beauharnais, who had been freed from a different jail. Neither had skills or a formal education, having been prepared from an early age solely for an advantageous marriage. But both had an idea about clothing, one of the few zones of expertise women were allowed. Society had been turned upside down. What if they did the same to fashion? What if they pronounced the pathetic chemise Térézia had been reduced to wearing in prison the ultimate in Paris chic? Térézia was France’s most glamorous victim of the Terror, so why not dress the role with brilliant éclat? Backing each other, the two proto-influencers would declare nothing the new everything. In one stroke they would vanquish the stays, the petticoats, the three-piece gowns, the silk brocades, the massive skirts, the lace, the baubles, and the towering coiffures. They would decapitate aristocratic style.

Contemplating their options as they dressed to dazzle and dominate French society in the fall of 1794, Térézia and Rose knew they had to work within the parameters of neoclassicism. Since the 1770s Europe had been reacting against the pastel tendrils of earlier 18th-century rococo style. Jacques-Louis David was the most prominent among a generation of artists whose sharp edges and edifying subjects invoked ancient Greece and Rome. In the mistaken belief that marble sculpture and columns had always been white (in fact they had lost their original gaudy paint), pure white became in some circles the artistic choice for the color of clothing. Women danced with flowing veils in salons and posed for stylized portraits, or tableaux vivants, in long, shapeless white drapery. Such drapery was only costume make-believe, but it did have the approval of artistic authority, including David’s.

Shapeless, however, was not what two women intent on seduction had in mind. The more authentic the classical costume, in fact, the less flattering it actually was: two solid wool rectangles as wide as an arm span, each folded over and belted at the hips, the two widths pinned at intervals along the shoulders and arms. That the cumbersome wool folds impeded movement posed no problem in antiquity: Wealthy women who could afford to be richly dressed were supposed to spend most of their time sitting indoors, spinning thread or weaving more fabric. But how could a modern Parisienne hop into a carriage, whirl around a ballroom, or gambol with her children in such voluminous mantles? In the fall, winter, or spring, she would shiver with her arms exposed and drafts coming in from all sides. And how could she fit the tailored redingote jackets and coats, fashionable since the 1780s, over wool rectangles bunched far beyond her shoulders? True antique style was not an option for functional daily northern European attire.

But one absolutely critical classical lesson had to be retained. Beneath their pinned wool rectangles, the women of antiquity had not worn anything—no stays, no petticoats. To eradicate underwear cages for daily wear would be a truly revolutionary move. Térézia could look back on her incarceration and know what it was like to live for weeks without the foundation garments of femininity. Amazingly, it was possible. Though Rose had not been as sartorially deprived, her own prison experience allowed her to empathize. The punitive chemise shift provided an idea; exactly how its poor, rough linen and sack shape could be made glamorous, however, was not immediately obvious.

THE DESIGNING FUTURE EMPRESS

Rose was no doubt the one who figured out the solution to their design problems. She proved throughout her life that she had a genius for transferring clothing from one style orbit to another. Raised on the French colonial island of Martinique, in the Caribbean, until she was 16 and married into minor mainland aristocracy, she had returned to Martinique to be with her family from 1788 to 1791. There, women of color (especially the lightest-skinned women of mixed race) wore a straight, sleeved, white cotton dress called a gole. Its silhouette could pass for classical, but the technical problem of fit around the bust and waist remained. It would be ideal, from the perspective of women like Térézia and Rose, who wanted to showcase their bodies, for garments to be anatomically shaped. That issue was solved by following the commercial trail of Caribbean gole fabrics right back to India.

The cotton available to women of color in the Caribbean could be found in a finer grade, called muslin, in the subcontinent. There, diaphanous Bengali muslin was already being made into garments with fitted tops and long, gathered skirts: the men’s jama. French colonists in India saw the jama on a daily basis, and Paris had been fascinated with the style in 1788 (as New York University art historian Meredith Martin has discovered), when ambassadors of the Tipu sultan, the Muslim ruler of the south Indian kingdom of Mysore, arrived on a diplomatic mission. Though the transparency of the jama could have been considered awkward, it corresponded to a fantasy that classical clothing had also been transparent. Not only did the jama have a waist, it was often worn with wide patka sashes that raised the waist intriguingly high. A sashed jama solved every problem posed by genuine classical clothing: A high, tight bodice reconciled the idea of a column with the desire for fit. A dress based on the jama would be light, compact, fitted where it counted, easy to layer over for warmth, and practical for active ordinary wear.

A dress worn without stays or petticoats was sure to be outrageous. A dress modeled on the clothing of people Europeans considered racially inferior was inconceivable. A garment borrowed from men would be illegal. But this was where the rage for classicism covered a multitude of sins. Europeans were so convinced of the superiority of their classicism that they were not going to identify the true origins of Revolutionary dresses. They would see the Caribbean gole, the Bengali muslin, the jama cut, the patka location of the waistline, and all they would recognize was their own idealized historic style. The scandalous elimination of bulky bone underwear would be impossible to ignore, but scandal would be mitigated by the appeal of classicism—with just enough outrage left over to attract the attention Térézia and Rose hoped for.

In the fall of 1794 they appeared in public together wearing columnar dresses so slender, sinuous, and mobile that onlookers were agog. And the brazen confidence with which they wore their outfits! Everyone in Paris wanted to see, and they could: in salons, at balls, and above all in theaters, where the brightest stars were not onstage but in the audience. (News traveled as fast from those style hot spots as the era allowed, like social media today.) The capital of fashion was conquered within months. Fashion magazines spread the news, from Moscow to Lima. It was the fastest, most total change of clothes in history.

By the winter of 1795–96, Térézia had commissioned from the painter Jean-Louis Laneuville a formal portrait of herself as if in prison. Though she had herself explicitly pictured in her dungeon cell, the rough linen chemise her jailers had mocked her with was revised as a pristine white muslin dress, jauntily cinched below her breasts, accentuating them, with a plaid madras scarf. The raven hair that the jailers had hacked off with knives appeared in the portrait to be artfully styled in symmetrical layers. Humiliation was transformed into prison chic. Trauma was turned into triumph.

It was one of the great style collaborations of all time. The two friends succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. Térézia took lovers at will, including the richest and most powerful men in France. She ended up an actual princess—all while having given birth to 11 children by five fathers. Rose married an awkward and obscure but mesmerizingly bold young army officer named Napoleone Buonaparte, from Corsica. On the occasion of their wedding in March 1796, he changed his name to Napoleon Bonaparte and she changed hers to Joséphine. In 1804 he crowned her Empress of France.

THE MUSE OF LIBERAL INTELLECTUALS

Meanwhile, a third fashion star rose to fame. Térézia and Joséphine had taken Paris by storm, and storms frighten most people. Their style was irrevocably, if thrillingly, associated with profligacy (translation: not-white-enough sexuality) and ruthless ambition, as well as with Parisian excess. “Madame Tallien [Térézia’s second married name] and the Empress Joséphine dancing Naked before [Directory leader] Barras in the Winter of 1797—A Fact!” announced the caption of a drawing by the hostile British caricaturist Gillray that represented both women as Black. Most women would have hesitated to imitate them had they not been balanced by another celebrity, whose reputation was as pure as theirs was wild. For such a radically new style to sweep Europe so totally and rapidly, complementary style personalities had to be in play. Juliette Récamier made the fashion revolution legitimate.

She too had emerged from the Terror with a dreadful predicament. Unconventionally, she had been raised by one mother and three fathers. Only one of the fathers, of course, could be legally married to the mother, and it seems the ménage à quatre decided it did not have to be Juliette’s biological father—if they even knew which of the three men had engendered her. One of the men, Jacques-Rose Récamier (he was not Juliette’s legal father, her mother’s husband) made by far the most money. During the Terror, the parental quartet assumed that Récamier’s banking wealth would send him quickly to the guillotine. To ensure that Juliette would inherit his fortune, her parents convinced her, at age 15, that marriage to Récamier was a necessary and very temporary expedient—he would not survive. But the Terror left Récamier unscathed, and the whole family resorted to loudly proclaiming Juliette a perpetual virgin.

The tactic was intended to deflect accusations of incest, but Juliette seized on it to dazzle the world with an all-white version of Térézia’s and Joséphine’s innovations. She symbolized what was most idealistic about the Revolution and became the muse of liberal intellectuals. Among the many ardent admirers in her prestigious salon were the great Romantic writers René de Chateaubriand and Benjamin Constant. In a reprise of Térézia’s and Joséphine’s style partnership, Juliette Récamier became the best friend of equal rights advocate Germaine de Staël. The heroine of Germaine’s most enduringly relevant novel, Corinne, merges her persona with Juliette’s, immortalizing their nonconforming relationship.

The Mighty Trinity

We live in a new era of the feminine star trifecta.

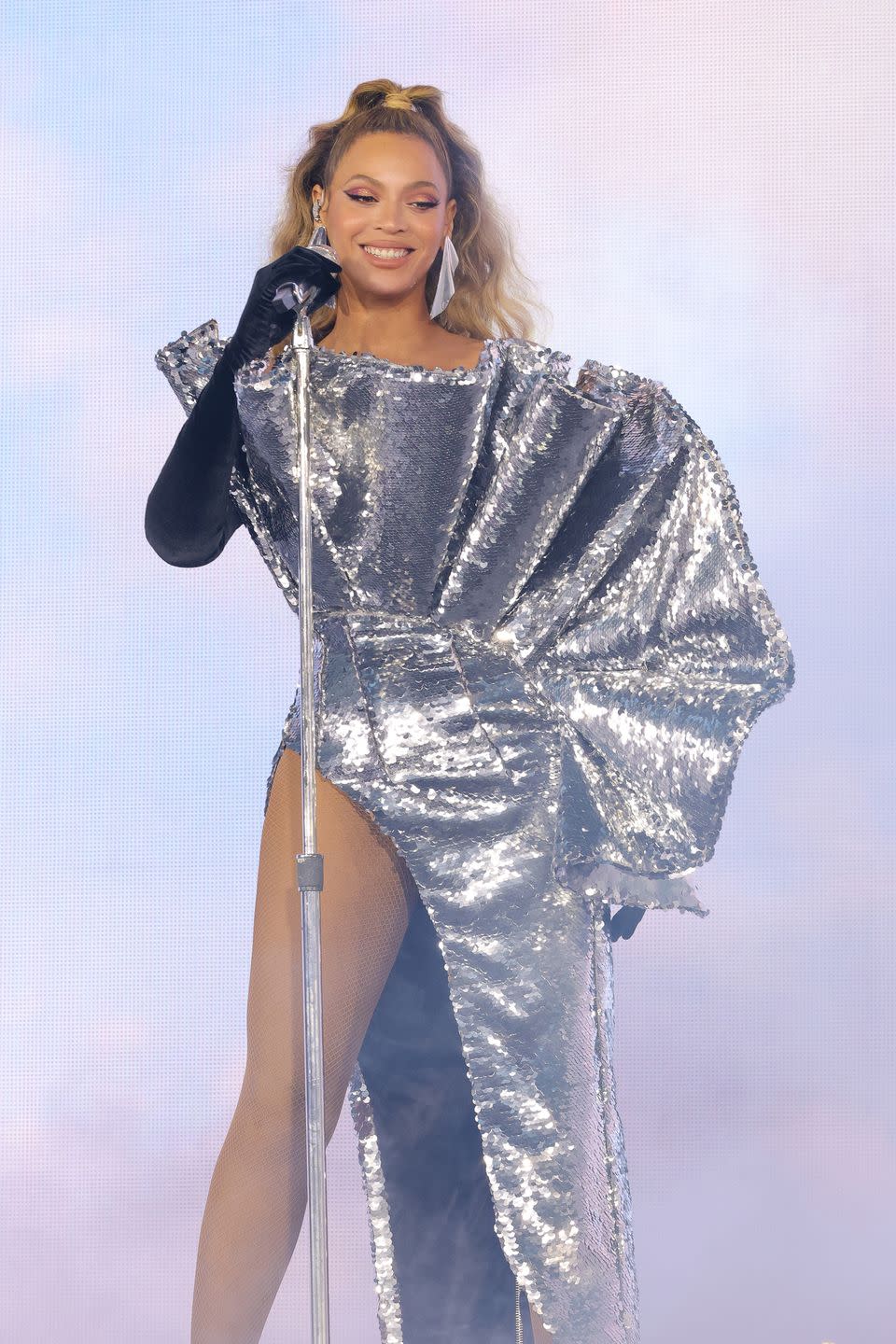

In antiquity, the Graces—Euphrosyne, Thalia, and Aglaia—personified all things pleasurable and beneficent. The Revolutionary Parisiennes—Joséphine, Térézia, and Juliette—were so culture-bending, divine-looking, and in tune with the era’s aspirations that they were called the Three Graces. And last summer’s big entertainment news? The triple whammy of Beyoncé, Margot Robbie, and Taylor Swift. Never have women so imperial, ideally beautiful, and beyond sweet entranced so many people, generated so much revenue, and expanded our style horizons. There’s something about a trio…

Beyonce

Our Empress of Music danced in the “Apeshit” video in front of David’s 1807 portrait of the coronation of Joséphine.

Margot Robbie

She has Barbie looks almost too perfect to be real, and she turns out to be as good as she is perfect—as Térézia did.

Taylor Swift

Like Juliette Récamier, she turns heartbreak into mesmerizing, dazzling, performances.

Just as Térézia had commissioned a formal portrait to publicize her fashion influence, so did Juliette: Madame Récamier, by David, from 1800. Sure enough, the portrait is still spreading Juliette’s influence to millions of visitors every year in the Louvre. It has been reproduced countless times, imitated, parodied, and hailed as the quintessence of the entire French revolutionary era. Across time, it has possibly accumulated more followers, so to speak, than any other fashion post. Ever since it was made, its ambiguities have commanded attention. Unlike more facile or charming portraits, this one perplexes. Juliette’s wary gaze, her partial turn away from us, her distance from us, and the emptiness of the scene are at once elegant and elusive.

For a portrait by the leading artist in Paris, Juliette dared to wear nothing but an absolutely simple white dress. It registers every curve of her turning torso and limbs as she looks over her shoulder. Her arms and throat are bare, as are her feet. One solid ribbon binds her natural curls. Her minimalist style concentrates our attention on the essential. It eliminates color, pattern, adornment, ornament, volume, and detail. The painting’s setting echoes her abnegations with its single, linear piece of furniture (to this day called a “Récamier sofa”), its extinguished Roman brazier, and its empty, sketched space. It may be the most famous unfinished painting of all time. David, as Harvard art historian Ewa Lajer-Burcharth has brilliantly proved, could not finish the portrait because he panicked in the presence of such a self-fashioned and self-possessed woman.

Look at the portrait from her point of view. Juliette was staring down the most eminent artist of her era, a man backed by Napoleon’s military and political power, alone in a big, dark room. All she had on her side was a dress. And a best friend, Germaine de Staël, who eloquently demanded rights for women. And a salon full of influential friends who defended the principles of democracy. And a generation of women who wagered that, in the long run, history would not forget their revolution.

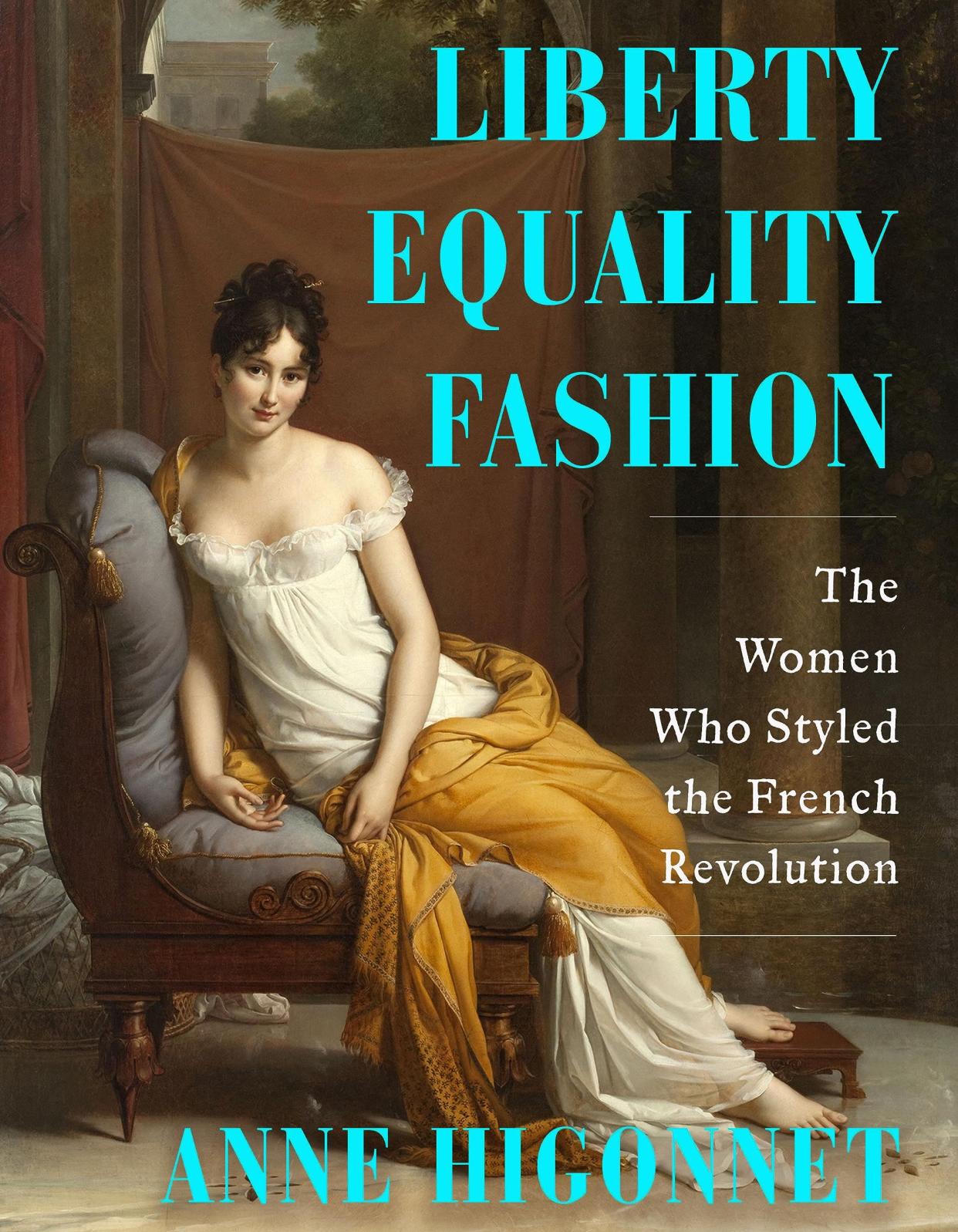

Liberty Equality Fashion: The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

amazon.com

$35.00

Everywhere a fashion magazine could reach, women imitated what was then called “the new style.” They rebelled against confinement in massive, rigid garments. Women moved, and everyone could see them move. A century before couturier Paul Poiret banned the Victorian corset, well over 100 years before Coco Chanel championed supple knit dresses, and more than 200 years before social media influencers came into existence, Térézia, Joséphine, and Juliette affirmed the physical presence of the female body in public, accessorized with shawls and tailored jackets, hair cropped short, with the first handbags over their wrists. The motto of the French Revolution was “Liberty, equality, fraternity.” It could also have been “Liberty, equality, fashion.”

Postscript: By the end of 1804, Napoleon had grown wary of this revolution. On the occasion of his December coronation, he turned the fashion tide by having the regalia designed according to his heavy, conservative taste. Fifteen years later women were back in tighter underwear cages and frillier froth than ever.

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion: The Women Who Styled the French Revolution by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company Inc. All rights reserved.

This story appears in the March 2024 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like