This 'rater' gets paid $10 an hour to teach Google's algorithm — and he's not alone

Google Search may feel like magic, but the engine’s efficacy relies on hourly employees who work for a subcontractor. In the internet age, these are, quite literally, the people who help you find the right pair of pants.

“If somebody's looking for pants on the internet, we want to make sure that it's actually a pair of pants — not a picture of a pair of pants or a sculpture of a pair of pants,” said Christopher Colley, who’s worked as a quality rater since 2017. “Sometimes, you need a human to actually do that.”

Colley is that human, and his work helps determine which pants you see. He’s an hourly, part-time employee at RaterLabs, an AI data solutions company whose only client, to Colley’s knowledge, is Alphabet-owned Google (GOOG, GOOGL). (RaterLabs declined to disclose any information about its clientele.)

However, Colley — whose lifelong fascination with computers began at 13, when he first built one from a box of old parts — is neither a Google employee, nor is he considered part of its “extended workforce.” If he were, he’d make $15 an hour and have parental leave, a standard Google set in 2019 following protests condemning its treatment of its TVCs, a frequently used acronym that stands for “temps, vendors, and contractors.”

Though all his work is tied to Google products and services, Colley makes $10 an hour. That's 70 cents above his home state of Ohio’s minimum wage, but well below the standard Google has publicly promised to those considered part of its “extended workforce.”

Right at the center of Google's business

Colley’s work is at the core of what Google does. As a rater, he evaluates search and ad-placement results for accuracy. When you Google “best pizza recipe” or “hobbies for Virgos,” raters like Colley are in their homes, on their computers, helping optimize search results. Colley, who studied photography technology in college, is specifically involved in Google’s biggest money-maker: ads. It’s hard to overstate the importance of ads to Google’s business: In 2021, about 81% of Google’s $257 billion in revenue was linked to its ads business, according to the company’s annual report. Colley doesn’t know for sure how big his team is — that’s not information RaterLabs offers workers, he says — but he believes he could have hundreds of colleagues, based on company-hosted social platforms.

Colley, who’d previously worked as an independent contractor for Microsoft and Apple, is also an organizer working with the Alphabet Workers Union (AWU), part of the Communications Workers of America (CWA). His organizing efforts among raters come as American labor is in resurgence, from the rise of the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) with its historic victory in Staten Island to the mounting success of unionization efforts at Starbucks. This week, workers at another Amazon warehouse in Staten Island rejected the ALU’s union bid, but the ALU has pledged to continue fighting, as have workers across the country.

"AWU-CWA is definitely looking industry-wide as far as linking our campaigns to the greater movement because organizing anywhere helps workers everywhere,” AWU steward Rachael Sawyer told Yahoo Finance

Raters of the Lost Ark

Most users never realize how much of search is driven by other human beings. Despite advances in AI, machine learning, and deep learning, “companies can’t rely solely on predictive analytics; that’s why the human element continues to be essential to search,” said Pat Condo, founder and CEO at independent search engine Seekr.

In 2017, The Guardian reported that about 10,000 raters worked for Google contractors, but Colley says he’s not sure how many there are today. In addition to Colley, Yahoo Finance spoke to four other RaterLabs workers, who requested anonymity. There’s not one type of rater, or one reason someone might take the job. For some raters, it’s their only job, while others rate for pocket cash. Some are near retirement-age and others are students. Still others, including some of Colley's co-workers, have disabilities or are single mothers, people who might struggle with the logistics of showing up at a traditional workplace, he said.

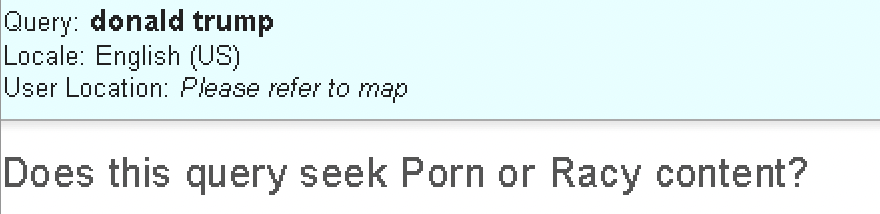

These raters, in some sense, are explorers. They’re exposed to the strangest corners of the internet, and their job is to teach the search algorithm what makes sense. An example of a question a rater has actually had to answer looks like this, from a file obtained by Yahoo Finance from one rater:

Colley didn’t feel comfortable discussing the specific content he’s evaluated, but anyone familiar with the weirdest recesses of the internet can imagine. Google says those who work specifically on search use publicly available Search Quality Rater Guidelines, which offers insights of its own. Though Colley himself doesn’t use these guidelines in his ads-focused work, the document helps illustrate what a rater might theoretically see. To make the magic happen, the raters have rules. For instance, a Wall Street Journal article about a diplomat that’s extensively sourced and written by two well-known reporters is considered to be a highest-quality page. Meanwhile, a blog that Google categorizes as “eating disorder encouragement” is rated a lowest-quality page, since it’s meant to facilitate harmful behavior and “contradicts well-established expert consensus.”

Without raters (and even with them), things can get weird fast. In 2017, The Outline reported that Google’s featured snippets were offering up full-blown misinformation, featuring a 2016 article that said now-former President Barack Obama was planning on enforcing martial law. These are the kinds of problems that raters need to help fix.

“Unlike algorithms, human search quality raters have real emotions and sensibilities, and are able to determine if Google’s results present quality issues related to fake news, racism, misinformation or violent content, as just a few examples,” said SEO expert Lily Ray.

Alone, one rater only has so much power, but as a whole, raters can indirectly inform and shape Google’s algorithm updates, she added. “Algo updates” often cause panic for SEO professionals, because they’re, in many cases, inextricably linked to company revenues.

“Google has been very clear that quality raters cannot directly implement what ranks in the search results,” she said. “But, in aggregate, the contributions of quality raters are helpful for Google to ensure its algorithms are on the right track.”

Home alone

Raters' working situations are unusual at best. The raters Yahoo Finance spoke to work from home, but they have no clue who their direct boss is, or if they have one boss or many bosses. They don’t even know their boss’ (or bosses’) name. RaterLabs confirmed this is true for many projects, though not all, they say.

“There are projects that provide transparency to who the project manager is for each project they select to do work on and are provided with the project managers’ contact information,” a spokesperson for Appen, RaterLabs’ parent company, said. “For other projects, a Quality Team alias is provided for communications.”

Across the board, the raters Yahoo Finance spoke to worry about waking up to a pink-slip-email, and two said they know of instances where people haven’t received an email at all –– the worker’s account was just deactivated. Even full-time employees at most companies can be fired at will, but the wall between raters and those who manage their work intensifies this anxiety. The raters Yahoo Finance spoke to, in all parts of their jobs, feel like they’re up against a faceless algorithm.

“In a termination notice, [employees] are sent an email from HR that notifies them of the termination and provides a contact for any questions,” according to the Appen spokesperson.

There’s also little transparency when it comes to raises, on the rare occasion that they’re given, added Colley. In his nearly five years at RaterLabs, Colley has never gotten a raise.

“We review pay on a bi-annual basis and adjust accordingly to ensure we are above minimum wage in each locale and in compliance with our fair pay policy,” the Appen spokesperson told Yahoo Finance. “Some projects have programs for senior-level promotions, which include a raise.”

But perhaps most of all, the work is isolating, and it’s difficult for raters to communicate with each other, said Colley. Tucked away in their homes, at their computers, all across the U.S., raters’ primary way of connecting with one another is a monitored company group chat. When joining the company’s messaging platform, raters are required to consent to, among other things, this statement in the terms and conditions: “RaterLabs shall have the right (but not the obligation) in its sole discretion to monitor, refuse, or remove any content for any or no reason.”

Accordingly, Colley has come to know his co-workers and their circumstances through his work with the AWU, Reddit, and Facebook, rather than through the company chat, he said.

If Colley’s not a Google employee, then what is he?

Colley’s officially an employee at RaterLabs, where he doesn’t have sick leave. He has other benefits, like access to an “Employee Assistance Program” that provides up to three counseling sessions annually.

The Fair Labor Standards Actdoesn’t address part-time employment, so there isn’t a federal standard for the benefits a part-time worker receives.

So, if Colley’s not a Google employee, what is he in relation to the tech giant? A rater like Colley is considered by AWU to be a vendor –– the “V” in TVC.

"TVCs are often people who are working the same job they could theoretically do at Google, but that's a door that's closed to them,” he said.

TVCs work all across Google. They are, including but not limited to, software engineers, data center technicians, content reviewers, legal assistants, program managers, accessibility support assistants, fiber installers, and even Waymo drivers, five non-rater sources familiar with the company told Yahoo Finance.

There’s absolutely no evidence that Google is breaking the law. Of the five workers Yahoo Finance spoke with, they’re all paid between $12.50 and $10 an hour, above the minimum wage in their respective states, which range from Colley’s home state of Ohio to Illinois and Florida.

Still, Colley and the other workers Yahoo Finance spoke to say the company is violating the spirit of the standards that it’s set for itself. They contend they qualify as members of Google’s extended workforce; Google disagrees.

Raters like Colley don’t qualify as members of the extended workforce, as RaterLabs “employs raters for part-time roles,” Google said.

“The raters work from home, use their own devices, can work for multiple companies at a time, and do not have access to Google’s systems and/or badges,” the Google spokesperson added. “As noted on the policy page, the wages and benefits policy applies to Alphabet’s provisioned extended workforce (individuals with systems and/or badge access to Google). We take our supplier relations seriously, and suppliers must adhere to our Supplier Code of Conduct.”

Colley’s work email, which he was directed to while being on-boarded by RaterLabs, is a Gmail account.

Holding Google to its own standards is complicated, as the company has incredible market power that’s inherently global, said Columbia Business School professor Eli Noam.

“Media power’s always been around, but what’s highly unusual today is that these companies are also global,” he said. “It’s not just domestic market power, it’s global market power.”

Much has been made of Apple CEO Tim Cook talking about the inevitability of regulatory oversight, and how he’s previously talked about self-regulation as the most effective kind of regulation.

“Self-regulation is a good concept, but the reality presents different problems,” said Noam.

It’s bigger than Google

Big Tech as a whole is heavily reliant on non-employee workers — Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and others all employ TVCs in significant numbers. Yahoo also employs temps and contractors.

This system isn’t new. In fact, it’s in Silicon Valley’s DNA, according to Louis Hyman, a historian at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Silicon Valley first emerged in 1960, “coming out of a world where there are lots of migrant laborers,” he said. In the late 1960s, these workers, who were often undocumented, shifted from agricultural jobs to industrial work. In that moment, Silicon Valley pioneered a “new kind of subcontracted capitalism” that was a drastic departure from Detroit’s highly unionized industrial economy. Simply, there have always been two kinds of workers –– those who are highly valued and those who aren't.

“This distinction is in the bones of Silicon Valley,” added Hyman.

Occasionally, tech companies have faced reckonings regarding their treatment of temps and contractors. In 2000, Microsoft paid $97 million to settle a case brought by 8,000 “permatemps,” but, generally, tech giants still work to exclude as many people as possible from their full-time workforce.

“Google’s keeping the workers and their relationship to the company at arm’s length and, while I'm saying Google, this is how it works [across the industry],” said Catherine Bracy, co-founder and CEO at TechEquity Collaborative, an organization focused on addressing economic inequality surrounding and directly tied to tech.

Indeed, Google acknowledges that it doesn't manage the raters directly. “We work with our suppliers to provide quality ratings as an external service,” the Google spokesperson said regarding how the company monitors its suppliers. “... The suppliers manage the raters directly, including the terms of their employment.”

The barriers dividing tiers of workers are far from invisible, and full-time employees notice. For instance, Google software engineer Ashok Chandwaney (who uses they/them pronouns) disapproved of the two-tiered employment system –– both at Google and at their previous employer, Facebook –– so they jumped at the chance to get involved with AWU. Chandwaney now is an AWU member and was elected as AWU’s finance chair. Though there are differences between TVCs’ conditions at Facebook and Google, it’s nevertheless “the same thing all over again,” they said.

"[Companies] don't want to know what's going on with the relationship between the worker and the staffing agency,” added Bracy. “That's all because they don't want to be seen as joint employers, because then they think they'd be liable for all sorts of things."

The algorithm still is magic

Arthur C. Clarke, the science fiction writer famous for ”2001: A Space Odyssey,” famously coined three “laws” about technology and our future. The most famous of these is: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

The finest technology, like the finest magic, inspires wonder in its audience. But the magicians who create that wonder don’t want you to know how the trick is done — they want you to wonder. For fear that knowledge will undermine their tricks, magicians rely on misdirection to preserve the mystery.

Users experience Google Search as a seamless experience engineered by an amazing algorithm. And that’s true. But that algorithm is diffusely trained by crucial workers across the country, many of whom are paid under the $15 an hour that Google promised to those considered part of its extended workforce.

Together, raters make important decisions: Does this image illustrate racism? What about pornography or drugs? The workers who make that call have invisible but ubiquitous power. They help Google decide what businesses succeed and which ones fail, and inform everyday searches from “best toilet paper” to “what should I watch tonight.”

We’re trained to think of Google Search as a perfect robot that can spit back out a pair of pants that’s right for you –– without showing you something insane.

"Every time someone says 'robot,' what they usually mean is... a worker who doesn't matter, a worker that's transitional,” said Hyman, the Silicon Valley historian. “That's the cultural logic underpinning so much of this."

Though Colley’s not a Google employee, like the rest of us, he will spend most of the day on Google. Today, his day’s gone something like this:

“I wake up, log on to the Google-hosted web interface where tasks are accessed from,” he said. “Those tasks are used by Google engineers to help inform their systems.”

Google Search is indistinguishable from magic, not only for what users see, but for what they don’t. It's time users start asking how the trick is done.

Allie Garfinkle is a senior tech reporter at Yahoo Finance. Find her on twitter @agarfinks.

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.