How a racist disinformation campaign kicked off Wichita’s 95-year war on marijuana

Wichita’s decision to repeal its marijuana laws could bring an end to the city’s 95-year war on “loco weed” deeply rooted in racism, disinformation and prohibition-era police tactics — a war that continues to disproportionately affect racial minorities.

Wichita’s decision to decriminalize brings the city to nearly full circle on its marijuana policies. The drug was legal in Wichita for 57 years before a racial panic helped touch off a chain reaction across the country that eventually led to a federal prohibition that remains in place.

The Wichita City Commission outlawed marijuana in the city in 1927, ten years before federal prohibition. In September, the Wichita City Council voted to decriminalize marijuana after city data showed Black residents are nearly nine times more likely to be charged with marijuana crimes in municipal court than non-Hispanic white residents.

In the 95 intervening years, Wichita went from being one of the first cities in the country with a marijuana ban to one of the last major cities to decriminalize it — despite a recent green wave of marijuana-friendly laws in surrounding states and nearby major cities.

Wichita is now aligned with the two largest cities in Missouri — Kansas City and St. Louis — and nearly 100 other cities that have recently reduced or eliminated low-level marijuana penalties.

But a statewide prohibition means Wichita pot smokers could still be arrested by Wichita police and face charges in state court. Marijuana remains illegal at the federal level, and Kansas is one of the few remaining states with a blanket prohibition.

All of its surrounding states have legalized or decriminalized marijuana. Recreational use is legal in Colorado. Medical use is allowed in Missouri and Oklahoma. Nebraska decriminalized possession of small amounts, but marijuana sales remain a felony.

The Kansas House passed a medical marijuana bill last year that died in the Senate. Senate leaders have said it could come up again in the 2023 session.

While Kansas voters field ballot questions on whether to grant the Legislature more power to regulate abortions or state agencies, voters in Missouri and Oklahoma will soon get to decide whether to legalize recreational use of marijuana.

Nineteen states, two territories and the District of Columbia have legalized small amounts of marijuana for adult recreational use, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. They have also reaped the benefits of more tax dollars, which are usually directed to boost funding for schools, law enforcement and local government.

The Tax Foundation estimates Kansas is forgoing at least $45 million in annual tax revenue by banning marijuana. But that could be a conservative estimate. Colorado, which legalized adult-use recreational marijuana in 2012, brought in an additional $423 million in tax revenue from marijuana sales last year.

Plant war

Marijuana was first viewed as a rather benign substance with some medicinal use. Then it was demonized and treated as a deadly, dangerous and highly addictive drug that would turn users into violent predators. Now, even the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency recognizes its short-term effects are no more serious than sedation, coughing and increased appetite. No overdose deaths of marijuana have been reported, according to the DEA.

Cannabis — especially hemp, which does not produce a “high” when smoked — had been embraced by the United States government since the Colonial Era. For five decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries Wichita newspapers ran ads promoting its use.

But in the 1920s, that all changed.

A fear campaign successfully convinced the Sunflower state that marijuana was a deadly drug that had been brought to Kansas by a growing population of Mexican migrants.

“Cannabis indica” became known as “loco weed.” “East India Hemp” became “Marihuana.”

A drug that had been advertised in Wichita as a cure for foot pain and common cold since the 1870s was rebranded as a “Mexican dream drug” that would turn white teenagers into homicidal maniacs.

Wichita’s ban was driven largely by a railroad agent’s racist disinformation campaign, which was amplified by a major media empire and law enforcement officials across the state.

C. H. Almond, special agent for the Santa Fe Railway in Topeka, stumped across the United States spreading racist lies about the dangers of cannabis and its proclivity to turn Mexican railroad workers into violent criminals. His claims were amplified by media mogul William Randolph Hearst, who saw hemp as a threat to his investments in the paper milling industry.

In a 1926 piece in The San Francisco Examiner, Hearst’s flagship newspaper, Almond is credited with discovering “the Kansas peril” and “directing the campaign to ban marijuana in Kansas under the guise of protecting Kansas youth from becoming addicted to “a narcotic worse, if possible, than opium, cocaine or heroin.”

Hearst’s newspaper chided Kansas for its inaction on marijuana and urged it to take a leading role in cannabis prohibit, as it had done by being the first state to outlaw liquor.

“School children are smoking it, prisoners are growing it secretly in the jailyards, grown-ups soak it in perfume. Scores have already gone crazy from it and hundreds are getting that way as fast as they can,” the article proclaimed.

The Examiner warned that Kansas was overrun with marijuana plants and addicts — and that “there is evidence that Kansas is not only consuming the drug but spreading it to the outlying states.”

It also advocated for total eradication of hemp plants, which the article falsely claimed could destroy the soil at Kansas farms.

Ottawa University’s student newspaper debunked The Examiner’s story almost immediately, writing that professors and researchers were unable to find any record of the plant in Kansas.

But, for the rest of the Kansas press, Almond became the leading authority in the state on marijuana. And the “loco weed” panic began.

Within a year of the San Francisco newspaper’s account, the Wichita Police Department declared a war on marijuana, and the Kansas legislature passed a state law criminalizing marijuana.

Wichita’s Mexican migrant population had increased from 135 in 1915 to anywhere between 934 to 2,500 in the early 1920s, spurred in large part by work on the railroads. At the time, the total population in Wichita was just over 70,000.

A 1920 report by the Interchurch World Movement said most of Wichita’s Mexican families lived in the “packing house district” along both sides of the Santa Fe railroad tracks north of 13th Street, which agents like Almond would have patrolled, and along the Union railroad tracks near Gilbert street.

Almond warned that Mexican migrants were bringing marijuana to Kansas and that “the big danger of the marihuana in this country is that its use might be taken up ignorantly by the flaming youth of the country who do not realize the dangers involved in the drug.”

He claimed “nine out of ten Mexicans who go crazy are the victims of marihuana smoking.”

The Wichita Eagle also indulged in the racist moral crisis.

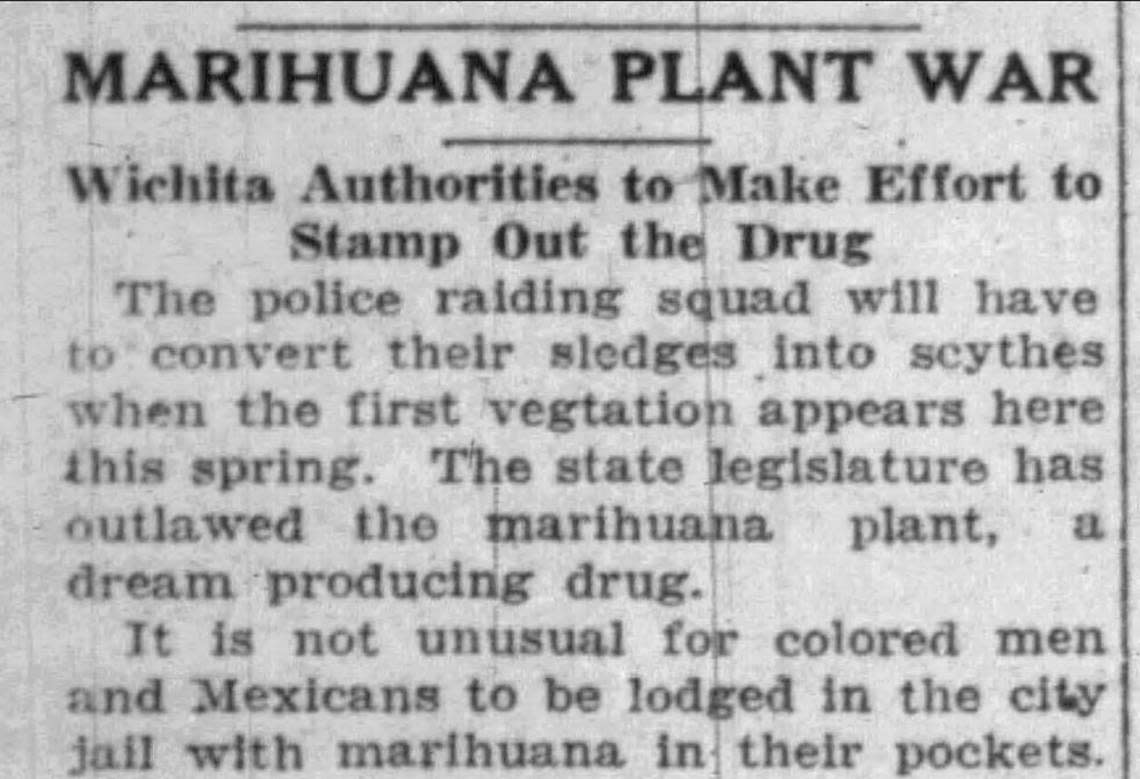

“The police raiding squad will have to convert their sledges into scythes when the first vegtation (sic) appears here this spring,” The Eagle wrote on March 21, 1927. “The state legislature has outlawed the marihuana plant, a dream producing drug.”

“It is not unusual for colored men and Mexicans to be lodged in the city jail with marihuana in their pockets,” The Eagle wrote. “In the Mexican section, the plant has grown unbothered for the past 30 years. A prolific plant, it has spread over a wide area. The supply in Wichita has always exceeded the demand.”

“The marihuana plant grows freely in Wichita along the railroad tracks,” The Eagle declared.

Wichita police didn’t wait for state law to take effect to start arresting for marijuana. The city’s first arrest was a 35-year-old Mexican man named Francisco Bezuo, arrested mid-April of 1927. The city attorney charged him with vagrancy and drunkenness because “police knew of no other term under which to book him.” He was fined $25 and sentenced to 60 days in jail.

In November 1927, the Wichita City Commission passed a law banning marijuana. It carried a $100 to $500 penalty and up to six months in jail.

The Wichita Eagle, a week after the city passed its ordinance, called marijuana “the low-class Mexican’s substitute for cocaine, heroin and other brain-destroying narcotics” that, when smoked, “produces temporary insanity – often of the homicidal type. It does not soothe like morphine, it does not stimulate like cocaine. It simply flogs the addict into a terrific activity which more often than not takes a criminal turn.”

The first conviction under the new city law was Manuel Barrerto, a 25-year-old Mexican man who received a 60-day sentence for a handful of “loco weed,” the Wichita Beacon reported Dec. 2, 1927.

Within five years, Wichita police began using marijuana as a pretense to increase patrols of Wichita’s Mexican neighborhoods, largely concentrated near the railroad tracks on the north and south sections of the city.

Wichita police told Eagle reporters in 1932 that rising popularity of marijuana among “Wichita school youths” had prompted “police investigations in the Mexican districts.”

By the late 1930s, the marijuana panic had spread across the country. The federal government outlawed it across the United States in 1937.

Except for a brief pause in 1969 and early 1970, it has been illegal at the federal level ever since.

New policy

The 2022 repeal of Wichita’s marijuana prohibition isn’t the first time Wichita has moved towards decriminalizing marijuana.

But it’s the first time in nearly a century that city officials followed through on the idea as states and cities around the country move towards legalization of recreational use, medical use or some form of decriminalization.

A city advisory board in 1977 recommended decriminalizing marijuana possession; but the proposal was ultimately dropped when the Kansas Attorney General’s Office provided an informal opinion that marijuana crimes could still be prosecuted in district court.

“That’s what we thought it would say,” Kenneth Kimbell, chairman of the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Advisory Board, said at the time. “I guess there’s nothing we can do.”

The situation hasn’t changed. But Wichita City Council members are banking on the fact the district attorney does not have the resources to prosecute all of the offenses.

“We’re going as far as we can as a city to stop ruining people’s lives,” Whipple said. “The city’s getting out of the business of increasing the number of young people and people of color with criminal records over something that’s legal in every state that surrounds us. We’re done waging war on our own talent pool.”

Still, Wichita falls short of other cities that have recently decriminalized marijuana.

The smell of marijuana has long been used as a tool by police to search vehicles and other property without a warrant. The City Council held that Wichita police can continue to make arrests for marijuana possession or use it as a reason to search their person or property.

Other localities have taken a different approach.

State legislatures, cities and courts have held that marijuana odors can’t be used as probable cause for searches of property, especially in places where its use has been legalized.

The most recent example is St. Louis. In December, its local government passed an ordinance decriminalizing marijuana and banning its police department from using the “odor or visual presence” of cannabis as the sole reason for a police officer to initiate an interaction with a civilian.

On paper, Wichita is no longer treating marijuana possession as a crime in municipal court.

In practice, the Wichita Police Department may still use it as a reason to initiate a search without a warrant and as probable cause to make an arrest. The Sedgwick County district attorney can also charge people in state court with misdemeanor possession for small amounts.