Pregnancy can be risky in the US. In North Carolina, the threat of death is even higher.

Tiffany Thomas was eight months pregnant and five days into a COVID-19 infection when it became impossible to breathe on her own.

Every night since testing positive, she sat in the front seat of her Ford Explorer, an escape from the stuffy bedroom where she self-quarantined. Surrounded by her favorite gospel music, she could briefly forget about the virus that forced her to watch her baby shower from a box on Skype and wreaked havoc on the daycare center she owned.

But this night was different.

Atari Thomas, her husband of eight years, waited inside the house as her typically short ritual stretched beyond 10 minutes, then 20.

After the half an hour mark came and went, he tapped on the car window.

From a lawn chair he propped up a safe 6 feet away, he could hear his wife’s quick, shallow breaths struggle in the humid August air. She hadn’t felt the baby kick for two days, she later told doctors.

They agreed it was time to go to the hospital. Just to make sure.

Even for young, healthy women, pregnancy poses risks. But in a country that has long maintained one of the worst maternal mortality rates among wealthy nations, pregnant women in North Carolina are particularly vulnerable.

In 2021, the year Tiffany Thomas entered the intensive care unit, about 80 North Carolina women died from pregnancy-related complications in the state, a mortality rate higher than the U.S. overall.

Those deaths nearly doubled here from 2019 to 2021 as COVID-19 spread, an analysis by The News & Observer found. But coronavirus wasn’t always to blame, leaving experts here seeking both causes and solutions.

Despite preliminary data showing a slight decline in pregnancy-related deaths and severe injuries since their pandemic peak, maternal health experts in North Carolina remain concerned by rates that are still higher than in 2018.

The increase underscores glaring inequalities in the care for pregnant women — especially for Black women like Tiffany, who in North Carolina are more than twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women.

Adding to this tragedy, the loss of young lives from pregnancy-related causes is often preventable, experts say. But the group tasked with investigating each of these deaths — and proposing ways to prevent them — is years behind in North Carolina.

It’s not just deaths that are on the rise. Data obtained by the N&O show more women in the state have experienced illness and injury during pregnancy and childbirth — sepsis or heart attack, for example — from which they narrowly survive.

Such complications are a “canary in a coal mine” for broad failures in health care, said Jacquelyn McMillian-Bohler, an assistant clinical professor at the Duke School of Nursing.

“Pregnancy is not an illness, and people should not be dying,” she said.

Pandemic pushed deaths to record highs

The month after his wife was admitted to the hospital blurs in Atari Thomas’ mind.

With his wife still in the ICU, he brought his newborn son home after he was delivered via emergency C-section.

Doctors initially said Tiffany was getting better. Then she got worse.

Tiffany’s oxygen levels dropped. Her speech became jumbled and incoherent. Eight days after arriving in WakeMed’s Garner emergency room, doctors transferred her to Duke University Hospital 37 miles away.

Then, came a call — the last call — from his wife, which he answered in the parking deck of Crabtree Valley Mall.

“Baby, I don’t want to go on a ventilator,” she said.

Everything would be fine, Atari reassured her. But secretly, he felt his own panic rising: ventilation had been his worst fear when he dropped her off at the emergency room.

“Well,” she said after a pause. “We gotta do what we gotta do.”

“We gotta do what we gotta do,” Atari agreed.

During the height of the pandemic, North Carolina’s hospitals were filled with pregnant women on ventilators or who were so sick from COVID-19 that they needed to deliver their babies prematurely, said Dr. Brenna Hughes, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Duke Health.

“I have never seen so many pregnant people in the ICU at one time,” Hughes said. ”And I hope to never see anything like it again.”

COVID infections played a major role in the increased maternal death rate during the pandemic, an analysis by The News & Observer found. In 2020 and 2021, COVID-19 was listed on the death certificates of 1 in 5 women who died during or in the year after pregnancy.

Even in cases where COVID-19 wasn’t on the death certificate, some deaths could have been brought on by the pandemic’s indirect effects on the health care system and society as a whole, experts say.

Accessing health care became harder, said Venus Standard, a certified nurse midwife and assistant professor at the UNC School of Medicine.

For those laid off during the pandemic, it became more difficult to afford medical bills. For families without a car, public transportation to a doctor’s office became less reliable. As daycare centers closed down, finding blocks of time for prenatal or postnatal appointments became near impossible.

Even if pregnant women overcame those barriers, Standard said fears of contracting COVID in a busy emergency room and healthcare staffing shortages could have dissuaded women from seeking help for potentially serious medical conditions.

“There were a lot of people that missed a lot of appointments,” Standard said.

Unsettling numbers, delays in reviews

But COVID-19 alone doesn’t fully explain the rise in pregnancy-related deaths in North Carolina in recent years, according to data analyzed by The N&O.

Between 2018 and 2019, for example, the number of those deaths jumped from 24 to 45, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. That pre-pandemic increase put the state’s pregnancy-related death rate almost 10 points higher than the rate for the U.S. overall.

In 2021, with COVID-19 outbreaks waning thanks to the rollout of vaccines, the gap between the U.S. and North Carolina death rate grew to more than 20 points.

Preliminary data from the state’s death certificate database shows pregnancy-related mortality dropped here in 2022. But deaths still remained several times higher than those recorded in 2018.

And a close examination of those women’s cases — and what could have saved their lives — isn’t likely any time soon.

When someone like Tiffany Thomas dies within weeks of a pregnancy, a group of experts in each state is supposed to find out why.

They comb through medical records. Weigh direct and indirect causes. Deliberate over how social factors like racism and poverty contributed to each death.

Their conclusions can help clinicians prevent pregnancy-related complications and save lives.

But the N.C. Maternal Mortality Review Committee’s analysis of these deaths is years behind schedule.

The committee is currently working on cases through 2019, a full year before COVID-19 began killing pregnant women like Tiffany.

More than 40 other states, The News & Observer has found, have analyzed and published more recent data on women who die during and after pregnancy than North Carolina. And when the state’s own maternal mortality review committee publishes its newest report later this year, it will still fail to meet federal health guidelines to examine cases within two years of each death.

Completing reviews in that timeframe, the CDC says, is an “essential step to providing timely information to stakeholders to inform targeted actions preventing future deaths.”

“We are concerned that our data are late,” said Belinda Pettiford, who heads the state health agency’s Women, Infant, and Community Wellness Section. “We are trying to elevate, and trying to bring in more resources, to bring on more people so we can get the data up.”

Pettiford said that unlike other states that “skipped some years,” North Carolina’s committee began examining deaths starting with 2014.

The state also has a smaller committee — a group made up entirely of up to 20 volunteers — than at least half of the country, an N&O survey of MMRCs nationwide found.

Pettiford said the group is “trying to catch up,” but has been challenged by both the pressures of the pandemic and a lack of staff. Members considered whether to skip some years to analyze more recent deaths, she said, but jumping ahead would mean leaving out hundreds of pregnancies from getting a full account of what happened.

“We feel all of the cases deserve that level of review,” Pettiford said. “The families deserve to know.”

Instead, a DHHS spokesperson told the N&O in July that the committee would delay the 2017 review to focus on deaths during 2018 and 2019.

In their first report, the MMRC found one thing most of these deaths have in common: they were likely preventable.

More than two-thirds of pregnancy-related deaths in North Carolina could have been averted with “one or more reasonable changes,” according to the MMRC’s December 2021 report, which analyzed cases between 2014 and 2016.

Hendrée Jones, a UNC School of Medicine researcher who has previously served on the Maternal Mortality Review Committee, said in many of the cases she reviewed, patients simply weren’t believed when they explained symptoms of serious conditions.

“What struck me was how many missed opportunities there were to intervene,” she said.

Optimism, pessimism about the future

North Carolina has made changes that maternal health experts say are likely to save more lives.

The newly passed Medicaid expansion, for one, means more pregnant women will receive pre- and post-natal care in a state where more than half of the babies born annually are covered by the program.

Ready access to vaccines and better COVID-19 treatments have driven down risks from the virus.

And the state’s Republican-led legislature, back in 2021, already expanded coverage for Medicaid recipients from two to 12 months postpartum.

North Carolina’s newly passed Care for Women, Children and Families Act contains millions to target several long standing problems affecting maternal health, like reimbursement rates for doctors and funding to cover housing for low-income pregnant women.

But that same law also includes abortion restrictions experts fear will set the state back on its ambitions to reduce maternal deaths.

Several studies have suggested that states with more restrictive abortion laws have higher maternal and infant mortality rates.

Women living in states that banned abortions after the fall of Roe v. Wade were nearly three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related complication, according to a 2023 report from the Gender Equity Policy Institute.

Marie Thoma, a maternal health researcher at the University of Maryland, said the impact of new abortion laws nationwide won’t be clear for years.

“There’s enough studies that we have on this to know the implications of these changes in policy,” she said. “We’re kind of seeing it anecdotally now: there’s lots of stories about these kinds of medical nightmares. The data will follow.”

Improving access to abortion and contraception also improves maternal health, says Duke Health’s Dr. Maria Small. And as impacts of the pandemic ebb, she’s concerned abortion restrictions will have a negative effect.

“I feel urgency, but I don’t feel panicked about the sharp increase,” Small said. “I do feel panic about access to reproductive health care.”

Families ‘deal with the emotions however they come’

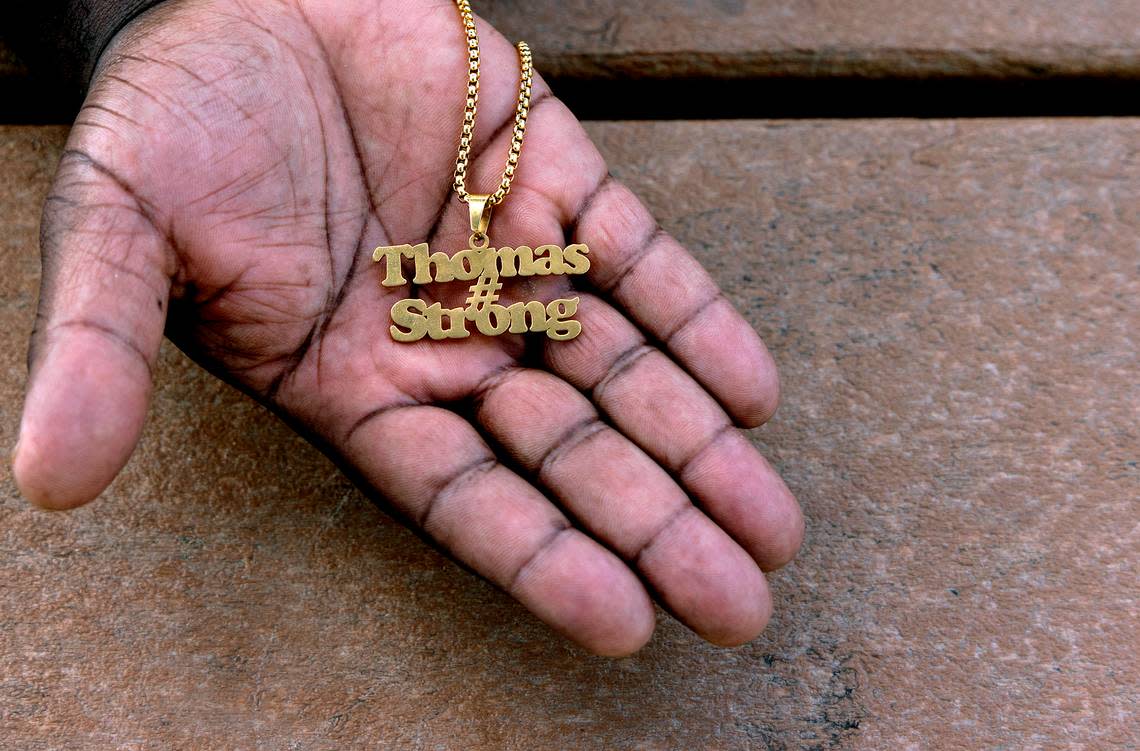

In the Thomas’ Raleigh home, photos of Tiffany are scattered throughout the rooms.

In the dining room, where she had scribbled out plans to open a daycare. In the foyer, where the couple shocked their family in 2013 with a surprise wedding. Propped beside the couch, where Atari was sleeping, newborn on chest, when Duke doctors called to tell him Tiffany was dying.

Atari wants Bryson to recognize his mother, even though he’ll never share a picture frame with her. With Bryson in his arms, Atari taps her photo, repeating “Mommy, mommy.” Most days, though, Atari doubts his son understands the exercise.

Bryson recently started referring to Atari’s mom, who moved in with the family to help out, as “mommy.”

“Grandma,” she gently corrects him.

Bryson — now a wriggly and stubborn toddler — pushes back.

“Mommy,” he insists.

Ultimately, Atari doesn’t press it. There was no right way for his sons to process their mother’s death. His own emotions are messy and complicated, a fact he doesn’t try to hide from his sons.

“We deal with the emotions however they come,” he said. “I can be talking to you right now and cry — and then laugh in the same sentence. It’s because I deal with it honestly. It’s a true emotion.”

For his middle son Braxton, who was 6 when Tiffany died, those emotions come out in bouts of inconsolable grief in which he screams for his mother over and over again. It’s more of a sustained feeling of disbelief for his 14-year-old son, Braylon.

“It’s just like my brain just can’t confirm that I’m really not going to see my mother again,” he said.