The Power of Teaching Your Kid to Swim

ABOUT 15 SUMMERS ago, when my oldest sons were six and eight, we started a nighttime habit. After dinner a few nights a week, I’d drive them the half mile to a boat docked in a salt pond, putter around three miles through the estuary to the outlet to the sea, and throttle out onto the darkening Atlantic Ocean in the fading light. Behind us, our wake would spread in a widening vee. At our feet would be a bucket of live eels.

It is about a four-mile run to a boulder—strewn bit of coast where striped bass and bluefish often feed. There, just beyond the shore break, with the boys standing at the gunwales on a rising and falling swell, we’d cast eels from the drifting hull out over the rocky bottom, sometimes under stars and sometimes encased in fog, until my sons, staggering with exhaustion, would lie down on the wet deck to rest.

On the good nights, they drifted to sleep beside a large cooler thumping with the tail slaps of heavy fish on ice. I’d keep casting until an hour somewhere around midnight, then reverse the journey to the dock and carry the boys to the truck. Often mist beaded their hair. Sometimes in the morning, when I rose for work, I’d find them in bed still in boat clothes.

So began a life of training children for lives tied to the ocean, the wild place just beyond our doorstep. Our family choices reached back further than this, when one of our kids had a health issue that the doctors said would preclude playing contact sports. We decided on the spot: We’ll make the children water dogs all.

The path was not direct. For several years, I was assigned to work in Moscow, a city about as far from the sea as we might get. The kids were young when we arrived. Our oldest son was four, his brother was two, and our daughter was a newborn. Two more sons were soon on the way. We used a swimming pool near our apartment to begin what we jokingly called “drown-proofing the kids.”

One winter, the pool’s heater broke, causing its water temperature to hover around 50 degrees, perhaps colder. After an initial sense of disappointment, we realized this was a blessing. The pool remained open but was almost entirely unused.

We bought child-sized wet suits and swam with the kids several days a week, acclimating them to water and cold at the same time and incidentally teaching the joys of a warming sauna after stepping blue-lipped from the chill. I remember those swims as some of the best of my life, drifting underwater as we played catch with a small rubber rocket and practiced retrieving it from the deep end.

When we returned to the United States in 2008 with water-confident children, we settled in a community just inland from the sea, where homes were more affordable but the ocean was not far. Salt water was almost in three cardinal directions. It became a primary setting for the kids’ fitness and recreation, a provider of social scenes, a source of food, and, with time, a gateway to employment and a grounding sense of wonder, challenge, and competence.

It also became a classroom. As the kids grew in size, strength, and endurance, they moved from boogie-boarding to surfing and spent longer hours at night and during weekends on boats. These pursuits spurred inquiries into weather, tides, seasons, and oceanic wildlife and gradually into the rituals of maintenance and repair. By the time they were teenagers, they were fluent in the migrations of many species of local birds, fish, marine mammals, and turtles and were developing other levels of awareness and skill, picked up at night in the wheelhouse or on days at a friend’s oyster farm.

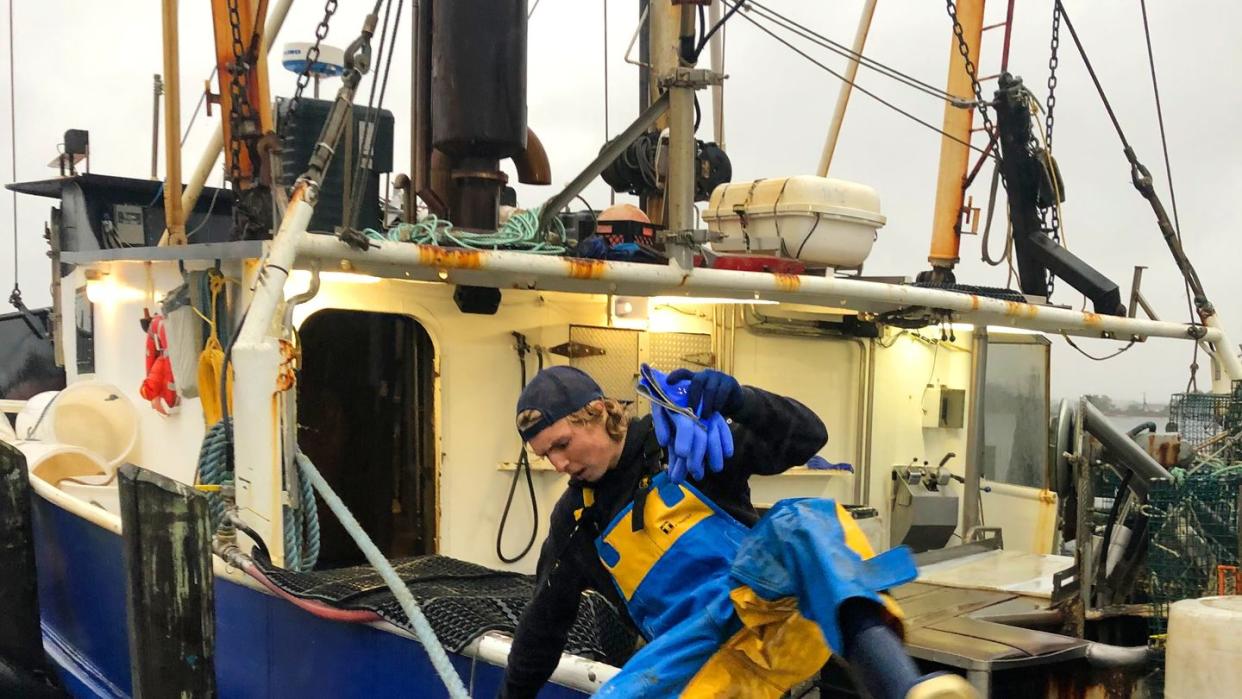

The children did more than grow. They grew hardy. The two oldest boys became lifeguards at a state beach, and four of the five kids began working for a local surf truck, which rents boards and offers lessons. Three of them worked their way up from doing menial tasks to serving as surf instructors; a fourth is too young to give lessons but is on a trajectory that makes his eventual instructor status feel inevitable.

When the kids started to catch clams and fish with me commercially, the sea was by then providing more than fitness and sustenance. It was a source of self-worth and cash and began summoning them independent of any larger family design. Our family fishing has grown to include soaking fish pots to catch black sea bass and scup and bull-raking for quahogs year-round. In season, with fresh seafood supplementing what comes from the gardens, we eat better than we ever have.

Forget for a moment these practicalities and physical rewards. The sea is wild and dynamic, a constantly changing wilderness in its own right. What it gives us goes far beyond what we can readily measure.

One morning when my oldest was about 11, I woke three of the kids around 2:00 a.m. and took them to the boat. It was a calm summer morning, with the air warm and the sea mirror-flat. For more than two hours, we steamed offshore under the stars, and as the twilight broke before 5:00 a.m., we set out two lines to troll. Petrels dipped around us. The sun painted the sky in soft pastels.

Within an hour, we had caught a bluefin tuna and were headed back toward shore while the kids, thrilled and animated, stood in the bow chattering. As we crossed Coxes Ledge, an offshore fishing ground where the ocean floor rises to a depth of about 105 feet, the surface was alive and rippling with schools of baitfish and a humpback whale rolled and blasted a plume of spray as we passed by. The children were wide-eyed with excitement.

I looked at the depth sounder; the screen was loaded with signs of bait and fish. Everywhere seemed thick with swarming life. All of this is close to home, a shorter distance than many of my neighbors’ commutes, and yet utterly wild.

Not all is reverie. Fear has intruded, too, and vigilance. A fishing captain years ago had a way of describing trips on the ocean. He was a former Navy pilot, methodical by training and nature. Venturing offshore, he said, is like traveling to space—you have only what you bring with you. When a trip turns bad, you may need backup radios or fresh water or well-charged fire extinguishers or first-aid kids and survival suits. We have all these and transponder beacons, too, and respect that on any trip, events could spiral out of our control.

The ocean often is inhospitable, frightening even. And though we keep close track of forecasts, almost every year we turn back in abysmal weather or closed in by fog. When the kids were small, their eyes were locked on the radar screen as we crossed shipping lanes with no visibility or when the hull shuddered in a steep, quartering sea. Now it’s all familiar. At this point, they are well beyond water-dogging. They’ve become creatures of their place and healthier for it, in most every way.

A version of this article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like