Prosecutors lobbied NC lawmakers to kill criminal justice reform bills, emails show

Cleveland County District Attorney Michael Miller wanted one of North Carolina’s top lawmakers to know how he felt about the state Innocence Inquiry Commission, a 17-year-old state agency created to review claims by people who say they were wrongly convicted.

“I think it is time for us to ‘defund the IC,’ ” he emailed House Speaker Tim Moore in May 2021.

Miller also urged Moore to kill House Bill 901, which would have made it easier for people to get their criminal convictions reviewed.

Moore’s emailed response: “I will handle it.”

The commission wasn’t defunded. In fact, its budget has increased. But the bill that Miller opposed died in committee that year. And a separate bill legislators approved this year will make it more difficult for people to challenge convictions.

North Carolina’s elected district attorneys wield great influence with Republican leaders in the General Assembly, interviews and hundreds of pages of emails reveal.

Working behind the scenes, prosecutors have lobbied to block criminal justice proposals that would eliminate life sentences for juveniles, take the death penalty off the table for those with severe mental illness and more.

They often win, reporting by The Charlotte Observer and The News & Observer found.

A chief element of their success: The N.C. Conference of District Attorneys, a state-funded association that vigorously lobbies the legislature. Many familiar with the organization say it has grown more powerful in the two and a half years since Chuck Spahos began doing its lobbying work.

Spahos declined a request for an interview. But in a written statement, he said most issues on the conference’s legislative agenda have unanimous support from North Carolina’s 42 elected district attorneys.

He said he has worked hard to ensure prosecutors’ views are represented at the General Assembly “and that we are viewed as partners in making our State a safe place to live,”

“Prosecutors are subject matter experts, and their knowledge, experience, and input are critical in developing sound public policy,” wrote Spahos, who previously headed the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia.

A force in the legislature

At a time when calls for reform have a high profile, the Conference of DAs and its member prosecutors have had enormous influence over criminal justice legislation debated in the General Assembly, defense attorneys, lobbyists and lawmakers told reporters.

The emails, acquired by a former ACLU staff member, confirm that when prosecutors took stances on bills, they often got results.

“If they don’t support something, it doesn’t happen,” said Chris Mumma, executive director of the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence. “That is because they can put out a call to arms and reach out to everyone in the House and Senate with personal connections.”

Many say this influence is growing, thanks to efforts by the Conference of DAs.

Established by the General Assembly in 1983, the conference represents all of North Carolina’s elected district attorneys. Its charge under state law is “improving the administration of justice.”

In 2023, the conference’s authorized budget was $2.1 million — about 40% more than the previous year. Executive Director Kimberly Spahos leads a staff of 27. She is also married to Chuck Spahos.

She earns $147,142 per year and Chuck Spahos makes $144,602, according to Office of State Controller data. Earlier this year the conference lobbied to move Kim Spahos into a more lucrative retirement system, which would have cost taxpayers $642,000. The proposal disappeared from a draft House budget after The N&O reported on it.

Rep. Pricey Harrison, a Greensboro Democrat, noted that criminal defense attorneys, unlike the elected DAs, do not have taxpayer-funded lobbyists. “Taxpayers are paying for prosecutors to come to us to lobby for bills that may be unfair to people. It’s just not fair,” she said.

Some experts, like Carissa Hessick, director of the Prosecutors and Politics Project at UNC Chapel Hill, have no problem with the idea of prosecutors exerting influence – as long as it is done in the open.

“We should think about prosecutors more as lobbyists who should be subject to some transparency requirements,” she said. “Voters should know about it.”

Instead, prosecutors often lobby behind the scenes – in private communications with lawmakers, emails dating from late 2020 to mid 2022 show.

‘Plaything of the wealthy, woke left’

The emails reviewed were chiefly between Spahos and various district attorneys, with lawmakers included in some correspondence.

When Miller, the Cleveland County DA, emailed House Speaker Moore in May 2021 about the innocence commission, Miller said it had “outlived its usefulness” and had become “the plaything of the wealthy, woke left.”

“It is my belief that they are quickly running out of cases that meet their charter mandate and have begun to actively seek ways to justify their crusade and perhaps even their very existence,” he wrote, copying Chuck Spahos and Forsyth County DA Jim O’Neill, then the conference president.

When asked about Miller’s comments, commission executive director Lindsey Guice Smith said the organization reviews an average of 211 claims annually and “is not running out of work.”

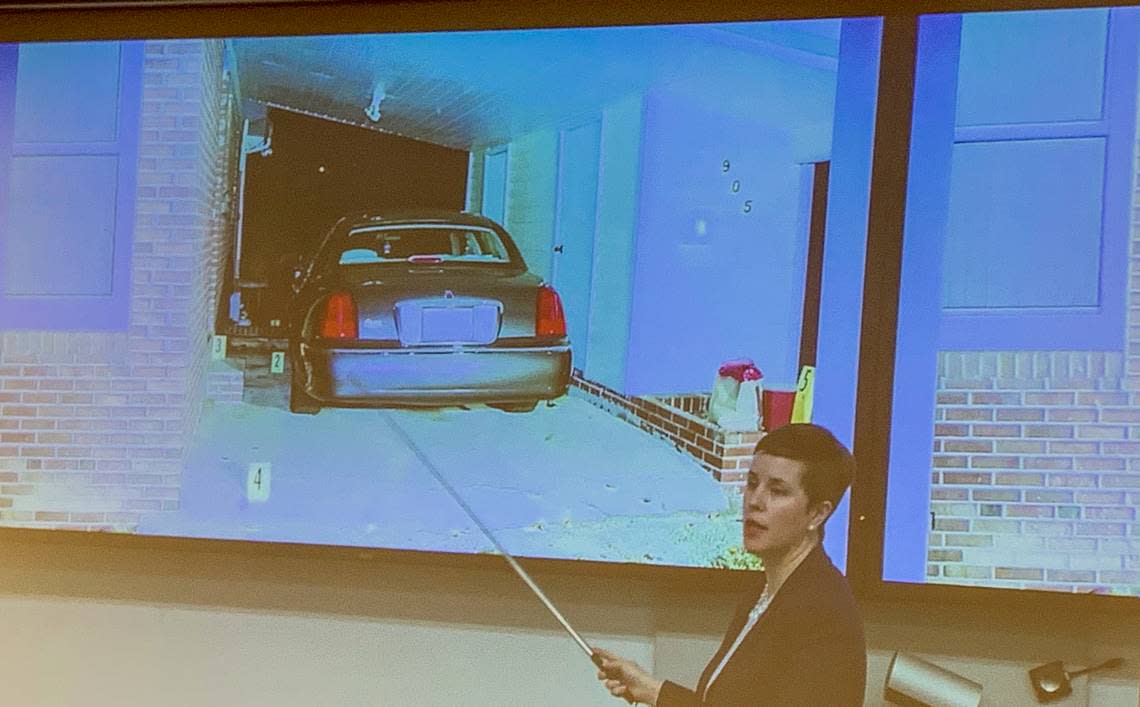

Created by state legislators in 2006, the innocence commission has reviewed more than 3,500 claims of innocence by people convicted of felonies such as murder, robbery and rape. And its investigations have led to 15 exonerations, according to its website.

Its authorized budget is nearly $1.5 million – roughly 50% more than the previous year.

If commissioners decide a claim of innocence warrants review, it is passed on to a three-judge panel appointed by the chief justice of the state Supreme Court, currently Republican Paul Newby. The judges consider evidence at a hearing and vote whether the person is innocent. A unanimous vote is required to dismiss the criminal charges.

Under House Bill 790, which became law this month with bipartisan support, the three judges will need to apply the North Carolina Rules of Evidence, a stricter and more time-consuming process than was previously required.

The provision requires those claiming innocence to clear more evidence-related hurdles and will likely make the hearings last much longer, Mumma said. Instead of simply presenting a police report, for instance, lawyers will have to bring in the officer who wrote the report to authenticate it.

When asked about Miller’s email calling for an end to the commission, Moore, who represents Cleveland County, wrote in a statement that he is “grateful for the input from my District Attorney and value his perspective.”

Moore added that “a number of our members had issues and concerns” about HB 901, the unsuccessful innocence commission legislation that Miller asked him to shelve.

A number of people who have had convictions reversed in North Carolina did not go through the innocence commission. A total of 72 people have been exonerated here since 1989, with 40 of those cases involving allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, according to the University of Michigan’s National Registry of Exonerations.

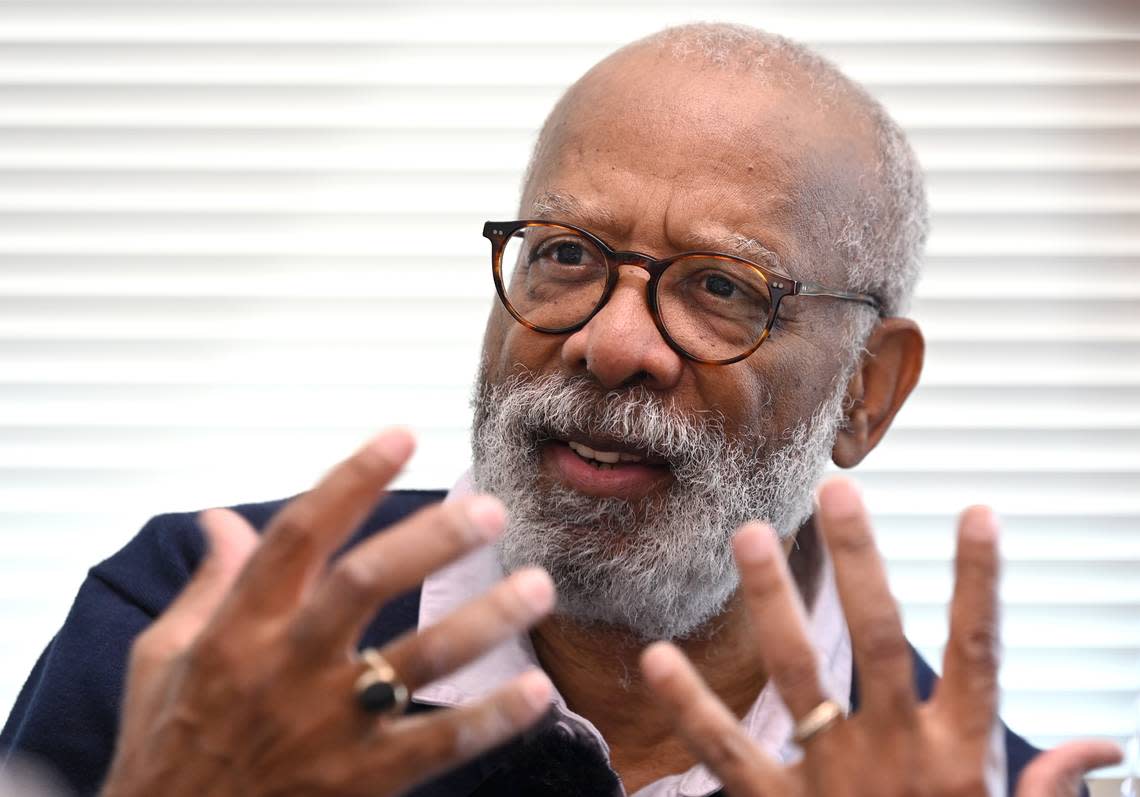

James Coleman, co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic at Duke Law School, said he views prosecutors’ opposition to making it easier for people to challenge convictions as more in their interest than the public’s.

“They are a political force that basically tries to cover up the deficiencies in the system,” Coleman said. “... When you can’t fix the facts, you change the law.”

No compensation for the wrongly convicted

In 2021, Chuck Spahos landed on the winning side after lobbying against House Bill 877, a measure that would have allowed people wrongly convicted to seek compensation from the state.

Under current law, the only people eligible for such compensation are those pardoned by the governor. The bill would have allowed a Superior Court judge to approve compensation if there is sufficient evidence to show the person was wrongly convicted.

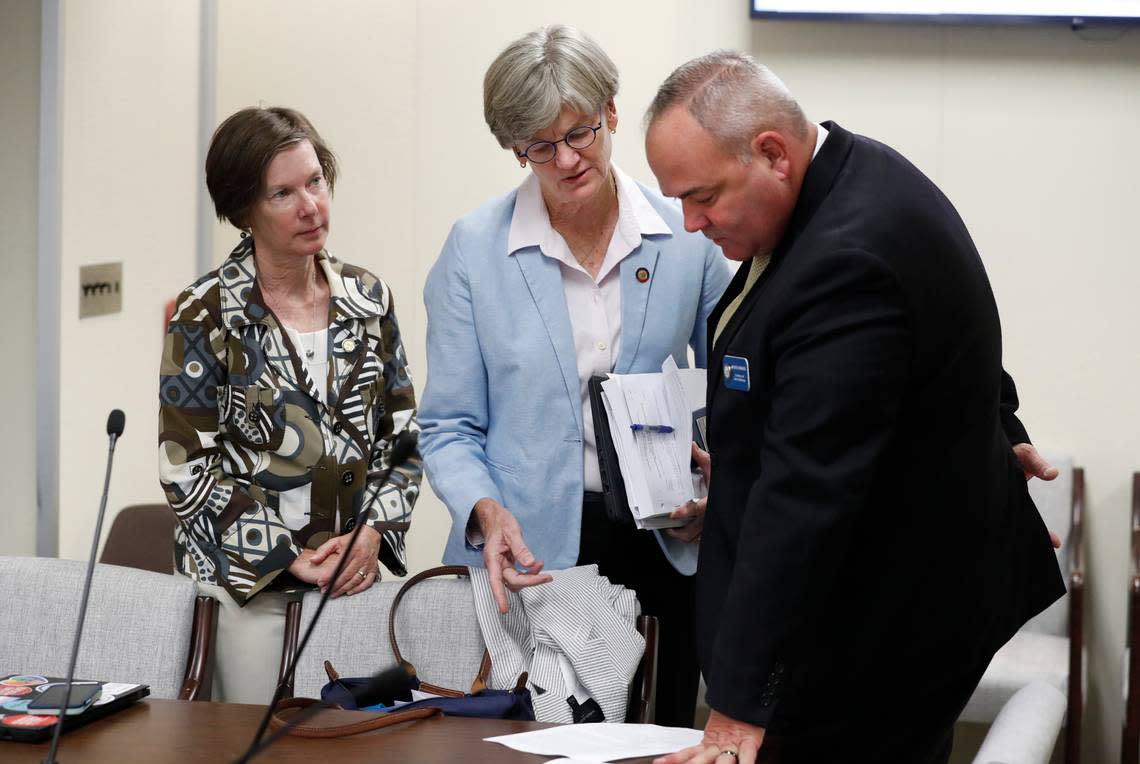

Spahos registered opposition to the bill in a July 2021 email to Rep. Harrison and Daniel Bowes, the ACLU’s former policy and advocacy director. He copied four powerful Republican lawmakers, including House Majority Whip Jon Hardister, who sponsored the bill, and House Speaker Pro Tempore Rep. Sarah Stevens.

“The bill does way more than providing for compensation for the wrongly convicted,” Spahos wrote, citing concerns that the bill would provide a new avenue for challenging convictions.

Coleman advocated for the bill. He argued that Spahos’ objections were “based on an erroneous and fundamental misunderstanding.”

The bill would not create a new way to challenge convictions because it would not apply until the conviction had already been overturned, he wrote.

Nevertheless, the bill died in committee.

Mental illness and the death penalty

Elected DAs frequently share their opinions about criminal justice reform legislation, the emails show.

In a March 2021, email to Spahos and other prosecutors, Randolph County DA Andrew Gregson strenuously objected to a proposal, sponsored by Hardister, to take the death penalty off the table for people with severe mental illness.

“This is simply a way to add complexity, increase expenses and require us spending additional resources on capital cases,” Gregson wrote

In his written response to questions, Spahos said conference members opposed the bill because it “blurred the lines and would cause a great deal of litigation in cases already resolved.”

That bill died in committee, too.

A ‘very persuasive’ lobby

Mecklenburg County District Attorney Spencer Merriweather stressed that prosecutors don’t always get their way. Despite repeated appeals to the legislature, his state-funded office is currently about 50 prosecutors short of recommended staffing levels, he said.

“For those who believe the influence of the DAs is outsized, they need look no further than the staffing of the DA’s office,” said Merriweather, who serves on the executive committee of the Conference of DAs.

Ernest Lee, a district attorney representing four Eastern North Carolina counties who serves as president of the conference, said it makes sense for prosecutors to consult with lawmakers “because we are the ones prosecuting the cases and have the requisite experience to provide insight into criminal justice issues.”

Hardister, who sponsored the compensation bill and the bill to eliminate the death penalty for those with severe mental illness, said the conference is “very effective” and “very persuasive.” District attorneys are respected, he said, because they have much more knowledge about crime and law enforcement than most lawmakers.

“When you’re contacted by a DA (who) says, ‘look, this bill is going to be good for public safety or bad for public safety,’ the average legislator might be compelled by that feedback,” he said.

Lobbying by prosecutors is by no means confined to North Carolina. A 2021 study by UNC’s Prosecutors and Politics Project found prosecutors in the U.S. “routinely support making the criminal law harsher.”

“In states like North Carolina, which elect prosecutors, we shouldn’t be surprised that they are political actors,” said Hessick, the director of the Prosecutors and Politics Project. “The question we should be asking is how do we want them to exercise that power.”