Police departments across U.S. are mandating LGBTQ training

Following a string of violence against Black trans women, LGBTQ activists in New York took to the streets in summer 2020 to draw attention to the deadly issue.

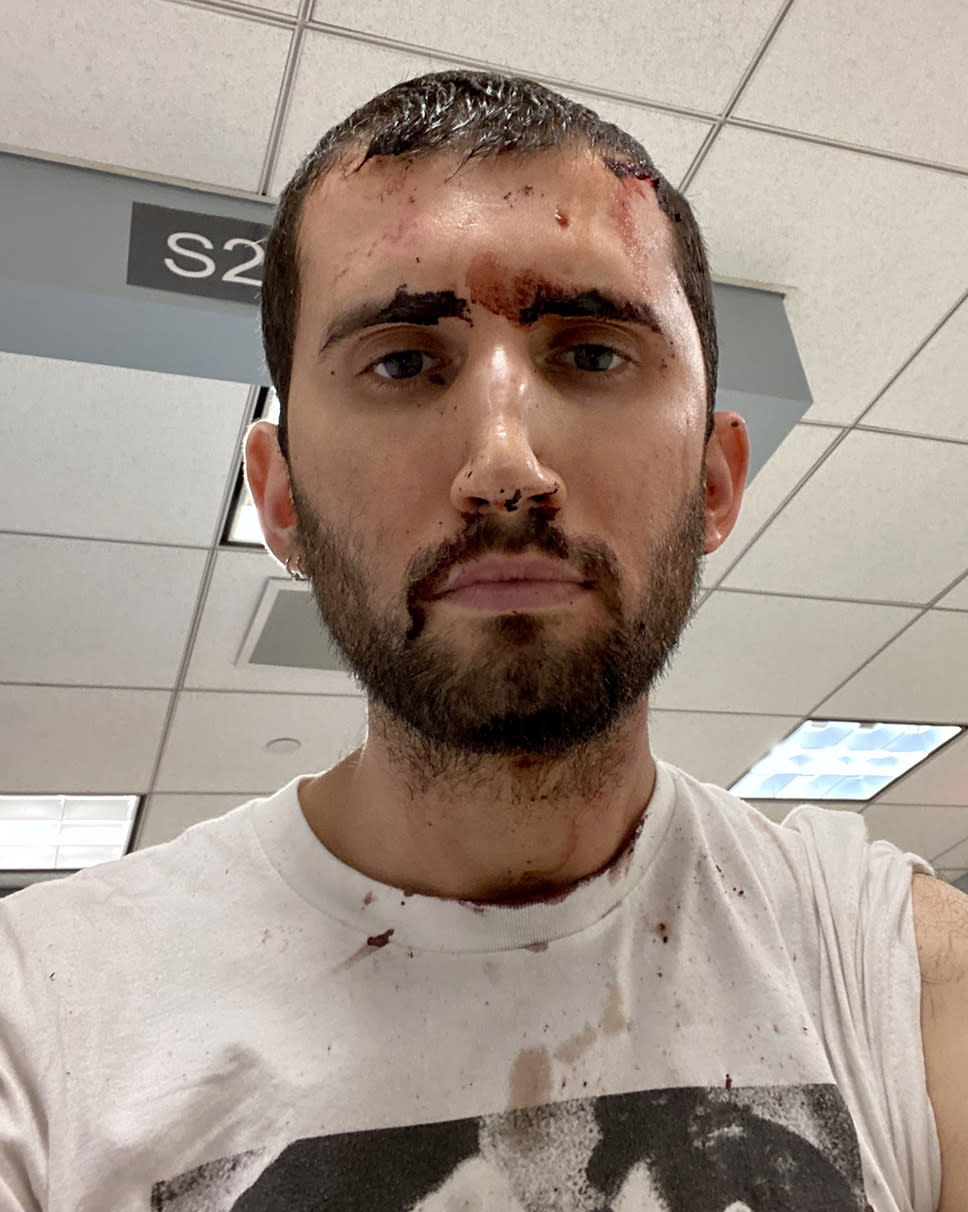

Jason Rosenberg and Marti Gould Cummings were among those who joined the June 2 demonstration in front of the iconic Stonewall Inn.

City officials set a curfew that night, and shortly after the 8 p.m. deadline, a number of the protesters — who were walking arm-in- arm — were arrested and violently attacked, according to Rosenberg, a member of the activist group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP.

“I felt excessive and violent force on all sides of my body and was knocked unconscious and woke up maybe a minute or two later,” he told NBC News. “My glasses were on the floor, my mask was off and my head was bloody.”

Despite the injuries he allegedly endured at the hands of police, Rosenberg said, he was denied medical treatment while in custody and ended up with a broken arm and 11 staples in his head after seeking treatment following his release.

“There was even a point where we were all sitting waiting to be transported to whatever detention center we were going to be processed at and people were chanting ‘Medic! Medic! He needs medical attention here,’” he added.

Cummings, a former New York City Council candidate who uses gender-neutral pronouns, said police officers were “really targeting protesters.” Cummings, who was arrested and spent more than 10 hours in police custody before being released, said they were unable to make a phone call and did not hear their Miranda rights.

“This is not an isolated incident, especially from the NYPD,” Rosenberg said. According to the New York City-based Legal Aid Society, 295 people in Manhattan alone had been “languishing in detention for 24+ hours” as of the morning of June 3, 2020, in the aftermath of widespread protests.

The NYPD did not respond to a request for comment on Rosenberg's and Cummings’ specific allegations, but the New York City Law Department did issue a statement at the time.

“The accusation that officers are retaliating against New Yorkers who are protesting is disingenuous, exceptionally unfair, and perhaps deliberately ignoring the fact that the Police Department is dealing with a crisis within a crisis,” the department said, according to a report published by the nonprofit news site The Marshall Project.

Treatment like the one Rosenberg and Cummings said they were subjected to are not unique to New York City. Reports can be found across the United States of police allegedly using excessive force against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people. There have also been numerous incidents in which LGBTQ individuals said members of law enforcement made disparaging remarks about their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to news reports, lawsuits and academic studies.

These incidents — along with the historically fraught relationship between law enforcement and the LGBTQ community — have led a growing number of police departments across the country to introduce LGBTQ awareness and cultural competency training for their officers. With trainings found from Washington, D.C., to Palo Alto, California, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach; rather, departments are crafting programs that take into consideration their specific communities.

'Lingering effects'

The relationship between law enforcement and the LGBTQ community has long been strained. Perhaps one of the most well-known examples of this rocky relationship is the iconic 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. The multiday protest — widely considered a pivotal turning point in the modern gay rights movement — was triggered by a police raid on the popular Stonewall Inn gay bar.

Throughout much of modern U.S. history, police officers were bound to enforce explicitly anti-gay laws — from local measures outlawing men from “impersonating a female” to the widespread criminalization of same-sex sexual activity. In fact, it wasn’t until the landmark 2003 Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas that gay sex was decriminalized throughout the country.

“These laws do have lingering effects,” said Christy Mallory, legal director at the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute, an LGBTQ think tank. “It can happen in subtle ways from being ingrained in some people’s heads that somehow same-sex relationships are inferior or should still be criminalized.”

“Given that this history is not so long ago, there are people who remember being wrapped up in that, which can come both on the law enforcement side and within the LGBTQ communities,” she added.

A 2015 report, co-authored by Mallory, highlights the numerous surveys, court cases and academic studies that document the alleged discrimination and harassment of LGBTQ people by law enforcement. Most notably, the report points to a 2013 survey of anti-LGBTQ violence survivors who interacted with police that found almost half (48 percent) reported they had experienced police misconduct in the previous year, including use of excessive force and entrapment.

Within the broader LGBTQ community, transgender individuals and queer people of color are at a particularly high risk of encountering police misconduct, according to other recent reports.

The National Center for Transgender Equality’s 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found 58 percent of trans respondents who said they interacted with police in the previous year alleged they had been harassed by law enforcement. The survey also found 57 percent of respondents said they were uncomfortable contacting police for help.

In response to allegations such as these, New York recently repealed an anti-loitering code — dubbed the “walking while trans” law — that transgender advocates said was penalizing trans women for simply walking down the street. A similar anti-loitering code has been on the books since 1995 in California, with state Sen. Scott Wiener recently introducing a bill that would overturn this law.

Black LGBTQ people, too, report more harassment from police.

A study published in June in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine by Devin English, a public health professor at Rutgers University, found 43 percent of Black sexual minority men experienced police discrimination in the past year. This unequal treatment had a range of negative effects on this community, including high levels of depression and anxiety, according to him.

While many explicitly discriminatory laws and policies targeting LGBTQ people have been repealed, there remains an issue with overpolicing of queer people, according to Mallory. She pointed to a study published by the Williams Institute in May that found lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer people are six times more likely than the general public to be stopped by police (data about transgender individuals were not available in the datasets analyzed).

One way this historically fraught relationship between law enforcement and the LGBTQ community has manifested over the past several years is in the decision to ban uniformed police officers from participating in Pride marches. The bans have been divisive, even within the LGBTQ community — and particularly among openly gay police officers.

One of the Williams Institute’s key recommendations to help bridge the divide, according to Mallory, is the implementation of LGBTQ sensitivity, diversity and specialization trainings within law enforcement departments.

Mallory said there are currently no federal laws that mandate LGBTQ training for law enforcement offers, but two states — California and New Jersey — recently mandated such training. More common, however, are individual police departments instituting these measures, though Malory said there’s no reliable data on how many have such training in place.

'We can continue to build trust'

A number of law enforcement departments have proactively decided to add LGBTQ programs to their arsenal of training courses. In fact, the largest local police departments in the U.S. — New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Houston and Washington, D.C. — all offer some form of LGBTQ training.

The Metropolitan Police Department in Washington — the sixth largest local police department in the U.S. — has been offering LGBTQ training since 2000, though it expanded its curriculum in 2015. Sgt. Nicole Brown, who has been a supervisor for the department’s LGBT liaison unit for the past three years, said her department was the first in the nation to offer such training.

Prior to the start of this training, negative attitudes about the LGBTQ community were reportedly pervasive within the department: In 1996, during a retraining of veteran officers, a word association exercise asked for responses to the word “gays.” The officers’ answers — which elicited no positive or even neutral responses — included “wrong,” “weird,” “faggots,” “AIDS,” “ungodly,” “don’t like ‘em” and “immoral,” according to a reporter for The Washington Post, who was present during the training.

Brown, who has worked as a D.C. police officer for 14 years, said she has seen first-hand the value of effective LGBTQ training for law enforcement. She regularly trains officers across the district in intensive courses ranging from how to approach investigating suspected anti-LGBTQ hate crimes to the importance of using the correct pronouns for transgender people.

But for Brown, there’s no substitute for on-the-beat training in the community, a community she herself is a part of.

“When officers come over to our unit, they get a chance to meet members of the LGBT community and hear their stories. They meet different community leaders that we interact with daily, then they go back to their respective districts and share what they’ve learned with their colleagues,” she said.

Informal, face-to-face meetings, she added, can go a long way to break down preconceived ideas police and LGBTQ community members may have of each other and help foster solid relationships. Brown said she often hears from fellow officers, as well as the people they police, that quick check-ins can open up conversations around similar experiences and make common ground easier to find.

Without building a rapport with LGBTQ residents, trust is hard to build, and awkward encounters are more likely, she said. Once officers get the cultural competency portion of training, they better understand some of the unique issues LGBTQ individuals face in the city and how the department can better support them, according to Brown.

“I think a lot of officers can become a little hung up on the fact that they don’t want to step on any toes and want to be as politically correct as possible,” she said. Following the training, she added, “their approach moves to: “I shouldn’t be nervous that I’m going to say the wrong thing, because I am treating this person like a human being, how I would like to be treated.”

While efforts are being made by the D.C. police to improve the relationship between members of the LGBTQ community and law enforcement, some local activists still have reservations about engaging with police.

Sultan Shakir, executive director of D.C.-based SMYAL, an organization that supports and empowers LGBTQ youths, said that while the training has some benefits, it fails to address the root causes of police misconduct.

“A training will help someone learn how to understand the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity, but it’s unlikely to really change someone’s attitude towards an entire group of people, particularly when that attitude is probably based on centuries of what society has told them to think about someone,” he said. “You can’t change that mentality in a two-hour training.”

Shakir said he would prefer a system where first responders are social workers trained on “supporting you from a trauma-informed approach” and “de-escalation.”

“We do our absolute best to try not to engage with the police department,” he said. “When it comes to our work, there’s a lot of very understandable fear, trauma, frustration and anger with a lot of the youth we work with around past engagements with the police.”

While the district has provided some form of LGBTQ-specific training for law enforcement officers for more than two decades, some localities — including Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Grand Forks, North Dakota — have only recently started to incorporate this type of training.

City officials in Grand Rapids approved LGBTQ training for police officers and firefighters in April, at a maximum cost of $20,000 for both departments as part of the one-off scheme. This pilot program includes learning about best practices in de-escalation for LGBTQ individuals, microaggressions, misgendering and the historical relationship between law enforcement and the LGBTQ community.

“We know that historically, the LGBTQ community has been arrested and incarcerated more [than the general public],” said Christin M. Johnson, lead oversight specialist at the Grand Rapids Office of Oversight and Public Accountability. “The point of these training sessions is to make sure that everybody feels welcome and that police are treating people fairly across the board.”

The Grand Forks Police Department recently announced it would launch a Safe Places initiative, which aims to train officers and local businesses to better support LGBTQ victims of hate crimes and harassment. First introduced by the Seattle Police Department in May 2015, Safe Places offers LGBTQ people the ability to report crimes to local businesses and organizations familiar to them that have signed up for the program.

“Some people aren’t comfortable with police coming to them, or them going to a police department,” Officer Brian Samson, the Grand Forks Police Department’s LGBTQ liaison, told the Grand Forks Herald in July. “Seattle found that when people go to a place they’re familiar with, or a local business, the people filing a complaint, or whatever’s going on — it’s easier to communicate with the police better, because it’s a neutral place for both parties.”

After introducing its version of the Safe Places initiative, the Seattle Police Department saw a major increase in the number of reports about harassment and hate crimes in the community. In 2014, 26 anti-LGBTQ crimes were reported to the department, and in 2015, when the Safe Place program had been in place for the last eight months of that year, the department saw 71 anti-LGBTQ hate crimes reported.

“We hope that the LGBTQ and minority communities see that reporting these crimes is important, and that they will be investigated and prosecuted, and that they know they can work with the police department and feel safe in doing so,” Seattle Police Department spokesman Sgt. Randy Huserik said.

'Institutional hatred'

While some police forces are voluntarily choosing to launch LGBTQ-focused initiatives, others are doing so after being sued by alleged victims of police brutality.

Gustavo Alvarez, a gay resident of Palo Alto, California, settled his lawsuit against its police department after accusing it of violating his civil rights, resulting in a settlement that included a $572,500 payout and a one-off two hours of mandatory LGBTQ-awareness training for all police officers in the department.

Alvarez alleged in his complaint that multiple officers used excessive force and specifically targeted him because of his sexual orientation. A surveillance video recorded Feb. 17, 2018, from Alvarez’s security camera at his home in the Buena Vista Mobile Home Park showed officers slamming him against a car, and one officer, Sgt. Wayne Benitez, pushing Alvarez’s head into the car’s windshield. The complaint says the officers initiated contact with Alvarez because one of them believed he was driving with a suspended license. It also alleges Alvarez was “mocked, made fun of and humiliated because of his sexual orientation” while in police custody.

The microphone worn by Benitez recorded him mocking Alvarez by talking in a “very flamboyant, high-pitched tone when he was pretending to be Mr. Alvarez,” according to Alvarez’s attorney, Cody Salfen.

Following the incident, Benitez was placed on administrative leave and retired from the department in September 2019. As part of the settlement, Benitez was required to make an apology to Alvarez, which reads in full: “I am sorry for my actions during the arrest of Mr. Alvarez. Regrettably I lost my composure, and hope the settlement allows Mr. Alvarez to move forward with his life. Sincerely, Wayne Benitez.”

“Alvarez was very traumatized by their bigotry,” Salfen said. “There was no secret that he was gay, and the officers definitely used that as a way to demean him in their prior contacts with him and also during this contact.”

Introducing LGBTQ awareness training is a starting point, according to Salfen, but it’s not enough to put an end to discriminatory police attitudes.

“When you have a culture that breeds and perpetuates hatred toward the LGBT community, there’s no way that a two-hour class can eradicate that institutional hatred. These institutional norms have existed and persisted for decades, perhaps even longer. You can’t just flip the switch and have that go away,” he said.

In October 2020, Benitez was charged with assault under color of authority and lying on a police report for his alleged actions during the arrest of Alvarez; he pleaded not guilty. The Palo Alto Police Department said it is not able to discuss the specifics of the civil case due to the ongoing prosecution in the related criminal case, according to James Reifschneider, acting captain of the department’s field services division.

Reifschneider, however, affirmed the importance of police officer training and said the department is going beyond the requirements of California’s Assembly Bill 2504, which mandates all new police officers in the state to receive training about the LGBTQ community.

“Our Department proactively chose to expand this training to include all of our sworn personnel (i.e. veteran officers as well) beginning in January 2020,” he said in an email. “We’ll be continuing to do it on an ongoing basis moving forward.”

State mandates

California became the first state to introduce mandatory training on sexual orientation and gender identity for incoming police officers, after former California Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 2504 into law in late 2018. The bill requires new recruits to undertake training in five unique areas, including understanding the differences between sexual orientation and gender identity and how these aspects of identity intersect with race, culture and religion, as well as learning appropriate terminology around sexual orientation and gender identity.

How best to respond effectively to hate crimes and domestic violence with LGBTQ victims and ways to create an inclusive workplace for LGBTQ coworkers are also included in the statewide training. While this law came into force on Jan. 1, 2019, it will be some time before all police officers across the state complete LGBTQ awareness education (and there’s currently no deadline for when officers must complete the training).

“Agencies really are just beginning to offer training now — it just got embedded into the basic training academies last October,” said Greg Miraglia, a former deputy police chief who helped draft the bill. Miraglia also serves as president of Out to Protect, a California-based nonprofit that supports LGBTQ officers.

The combination of Covid-19 restrictions and the logistical difficulty of some police agencies to send their agents away to train are driving an increase in online training. Miraglia estimated that about 1,000 officers have participated in the online training so far and approximately 2,000 have taken part in in-person training.

“In-person training is really the best way to go, because you give people a live chance to interact and to get answers to their questions immediately,” he said. “The online course is somewhat interactive with scenarios to respond to and, of course, it has the same components that a face-to-face class has. It’s definitely better than nothing.”

The State of California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training will not certify anything less than two hours on the topic, with Miraglia recommending at least four hours of LGBTQ awareness training.

“We can get the basics done well in four hours. But, in my view, cultural competence training is a perishable skill, and doing refresher training on issues like how to respond to domestic violence and the nuances of dealing with a hate crime victim who happens to be part of the LGBT community, is important moving forward,” he said.

Across the country in New Jersey, on Nov. 20, 2019, Transgender Day of Remembrance, the state’s then-Attorney General Gurbir Grewal issued a directive announcing all law enforcement professionals in the state would receive mandated training on how to best interact with transgender, nonbinary and gender-nonconforming individuals. As part of these new rules, officers are directed to address all people by their chosen names and pronouns, even if these don’t match official records. Elements of the directive include the entire LGBTQ community with, for example, police officers required to “not delay responding to, fail to respond to, or treat as less important, any call or request for service or assistance because of the individual’s actual or perceived gender identity or expression and/or sexual orientation.”

Law enforcement officers must also not disclose an individual’s sex assigned at birth unless there is a proper law enforcement purpose. The rise in hate crimes against transgender people was one of the reasons Grewal gave for issuing the directive.

“Building on the extraordinary work of law enforcement agencies across this country and right here in New Jersey, we’re ensuring that our officers will act in ways that promote the dignity and safety of LGBTQ individuals, whether they are victims, witnesses, suspects, arrestees, or other members of the public,” Grewal said in a statement. “Only by having the trust of our diverse communities can we fulfill our mission of protecting all New Jersey residents.”

Mixed reviews

Some experts, like Mallory at the Williams Institute, say the increase in LGBTQ-specific police training is a positive step forward.

“Not only can training help the LGBTQ community, but it can help police departments do their job better, especially those that are really invested in community policing,” she said. “These trainings can really help get to a place where LGBTQ communities feel comfortable working with law enforcement, and actually enable police to do their jobs better and more safely.”

Tailored LGBTQ training is an important development, according to Mallory, but it’s not the final step. She said it’s critical for these initiatives to incorporate the idea that people with multiple marginalized identities can be put at an increased risk of over-policing, resulting in negative outcomes.

“Those LGBTQ people who are in communities of color can see the issues relating to over policing being amplified,” Mallory added. “These issues need to be at the forefront of any kind of reform and training.”

Others, like Rosenberg and Cummings, are less optimistic.

“I don’t think any type of sensitivity training could work,” Rosenberg said. “A lot of us are past the point of any attempt to reform a very corrupt and broken system.”

For Cummings, a ground-up transformation of policing in the U.S. is the only way forward for law enforcement. In New York City — where LGBTQ training is provided by the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL) for both new recruits and veteran officers — Cummings wants the police commissioner to be a civilian and rulings from the Civilian Complaint Review Board, the NYPD’s oversight agency, be binding.

“We need to take from the inflated police budget and put funding back into violence interrupters and harm reduction efforts in the community,” they said. “Across the board systemic racism and homophobia is in play within policing, so it goes beyond training and budget. This has been going on since the beginning of our country.”