Please, no more drive-thrus on this major Boise street, city agency says. This is why

Maybe you like driving through fast-food and coffee shops. But Boise officials looking to spruce up one of the city’s most important streets say they’ve had enough of them.

A developer wanting to build a drive-thru on State Street could soon be penalized for trying. Drive-thrus cater to cars. And Boise’s leaders want to promote other types of transportation on busy State. More people riding buses, walking or bicycling would reduce the number of cars on the road, a good thing for traffic and the environment.

City officials can’t tell people how to travel, but they can make it harder for developers to receive public money for playing to the automotive culture.

Boise’s urban renewal agency, Capital City Development Corp., wants to transform State from a car-dominated road to a corridor with several ways to easily move around.

At its Monday, July 11, meeting, the agency’s board reviewed the staff’s proposals to incentivize, or disincentivize, certain types of development. Included in a proposal was penalizing developers for drive-thrus on State.

Capital City Development Corp. uses the money it collects in property taxes to promote urban renewal. It can pay for certain development costs in urban renewal districts. It can use its money to steer developers toward projects that further city goals. If a developer improves a sidewalk to make it accessible and pedestrian-friendly, and builds street lights, benches and bicycle racks, the agency can reimburse those costs. Reimbursements may range from tens of thousands of dollars on small projects to millions of dollars on big ones.

To measure whether a developer’s project aligns with what the agency wants, the agency grades the project on a scorecard. In this case, a developer’s hopes of being reimbursed would take a hit for building a drive-thru.

Based on the draft of the State Street district scorecard presented July 11, the maximum theoretical score would be 417 points. In reality, anything with 140 or more points receives the highest possible grade.

A potential development receives eight points if it’s a multistory building with a combination of uses on different floors, seven if it includes affordable housing, and five if it includes middle-income or workforce housing. There’s also a five-point bonus if there’s a “minority owned or local business” proposed.

And negative-eight points if it has a drive-thru.

Capital City Development Corp. wants “development that is less car-centric and more compatible with multiple modes of transportation like walking, biking and busing,” spokesperson Jordyn Neerdaels said in an email. “Something more car-focused, such as a drive-thru, requires curb cuts and can create car traffic that spills over onto the sidewalk, which is a safety concern as it increases potential conflict between bikes, pedestrians and cars.”

Deducting points for a drive-thru isn’t new. The scorecard for the Westside, 30th Street, River Myrtle-Old Boise, and Shoreline districts each deduct 10 points for drive-thru retail.

Nonetheless, Commissioner Ryan Erstad, an architect for Rocky Mountain Cos., a Boise developer, questioned whether deducting points is appropriate.

“We’re the carrot and we’re not the stick,” Erstad said. “So we should be encouraging the uses we do want to see. But if it’s allowed in the zoning, we shouldn’t necessarily discredit it either.”

Mayor Lauren McLean, a Capital City Development Corp. board member, recommended having the staff review the proposed scorecard again before any decisions are made.

The point system “would make more likely our arrival in investments in proposals that further our design goals, urban goals, mobility goals, etc.,” McLean said. “... I know that (City) Council, the city and (Capital City Development Corp.) staff and city staff are really keen on making sure that public resources are going into developments and projects in a way that furthers our shared goals rather than end up doing the basics.”

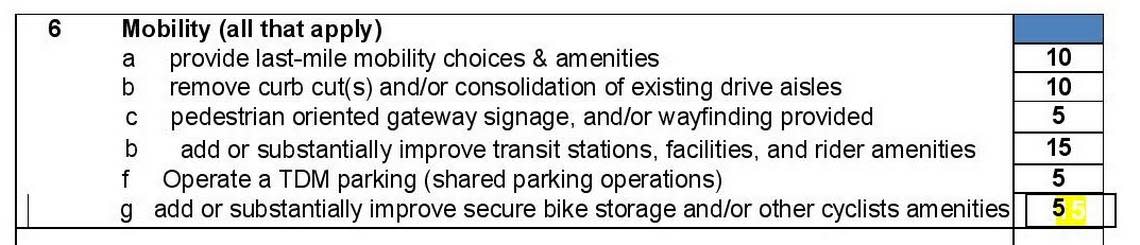

Project Manager Alexandra Monjar said the major change in the scorecard was adding a section for mobility, which awards points for improving pedestrian signage and bicycle storage. The proposed scorecard also expanded the connectivity section with added points for multi-use pathways, sidewalks and improved street crossings for pedestrians and cyclists.

These additions reflect the importance of transportation options other than cars, which is the core of future plans for the State Street district.

“Any time you put a score on anything, it can be really challenging,” said Capital City Development Corp. Chairwoman Dana Zuckerman, a housing developer and land-use planner. “(I) appreciate your continued effort in trying to get this as perfect as possible, knowing it will never be perfect.”