Planned Midlands town park would share the story of soldier blinded in civil rights case

More than 75 years after a major injustice, one small South Carolina town is trying to make amends for its racist past.

Batesburg-Leesville is seeking money to dedicate a new park in the name of Isaac Woodard, a Black World War II veteran whose name became associated with the town when he was beaten and blinded in the town jail.

Town officials are seeking funding from various sources to construct an Isaac Woodard Unity Park on the site of the former jail.

The town hopes the site will be added to the U.S. Civil Rights Trail. It will include a memorial to Woodard and information about what happened to him in an incident other communities may have wanted to keep under wraps.

“I hope it will draw people in, but also it’s just something that needed to be done,” said Mayor Lancer Shull.

What happened to Woodard in this western corner of Lexington County became a national story that gained attention from celebrities, intervention by President Harry Truman and helped to launch the modern civil rights movement.

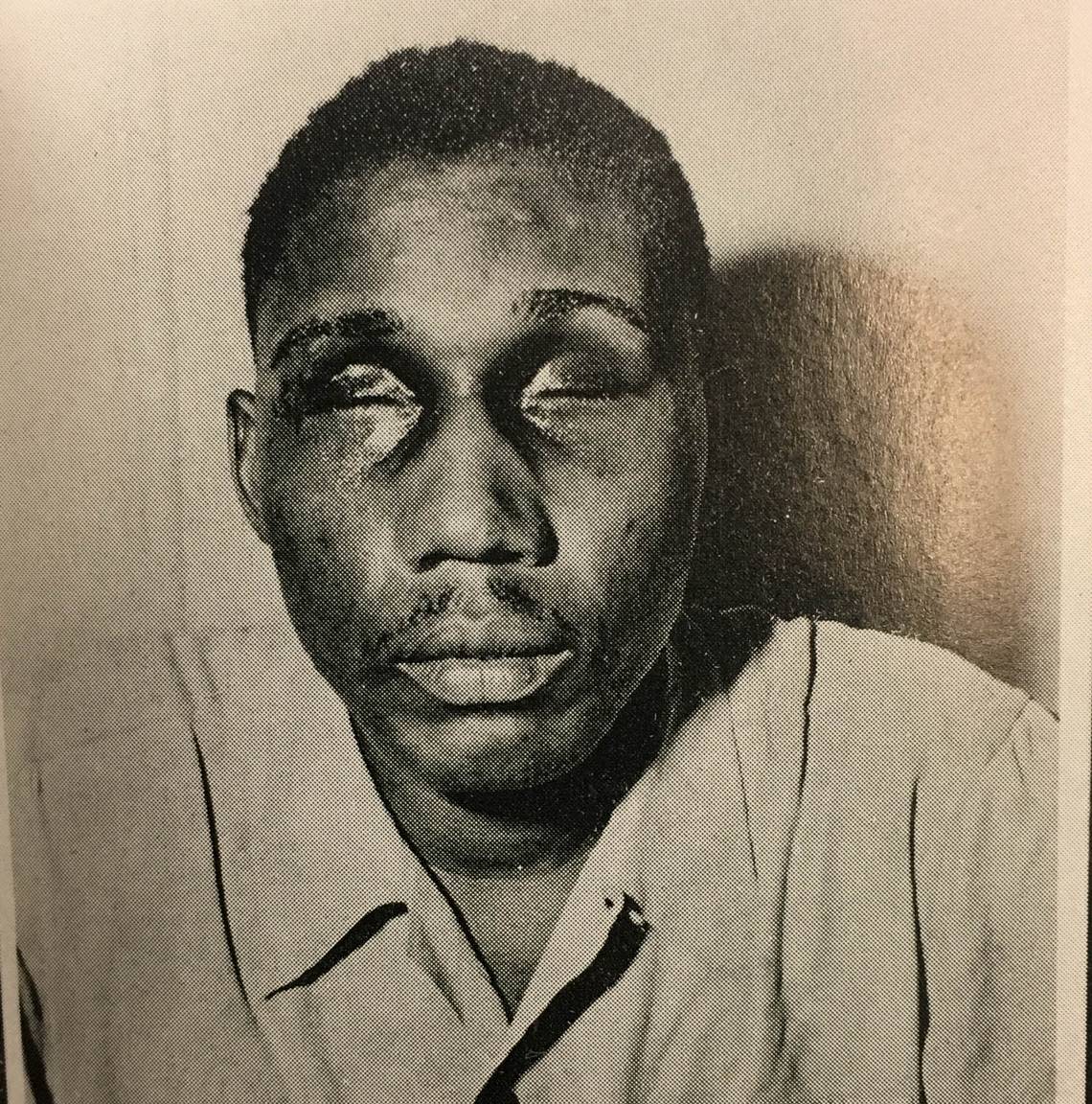

In 1946, Woodard was returning from serving in the Pacific in World War II. He was still wearing his Army uniform on the Greyhound bus that was taking him home. But when the bus stopped in the small town of Batesburg, Woodard was taken off the bus by police after arguing with the bus driver over a bathroom break, and was beaten so badly in the town jail that he was blinded for life.

Such beatings were common in the Jim Crow-era South, but Woodard’s case received outsized attention because of Orson Welles. The famed movie star and director featured Woodard’s story on his national radio show, where Welles discussed the case for several weeks.

Batesburg police chief Lynwood Shull (no relation to the current mayor) was ultimately indicted on federal charges, but was acquitted by an all-white jury in Columbia.

Woodard’s case was credited with Truman’s decision to integrate the armed forces in 1948. It also influenced Judge J. Waties Waring, who presided at Lynwood Shull’s trial, when he later issued an opinion rejecting segregated schooling that laid the groundwork for the Brown v. Board of Education decision, according to a book on Woodard’s case by federal Judge Richard Gergel.

Town Administrator Ted Luckadoo estimates the park will cost $3.7 million, including a planned statue of Woodard. The planned park will be part of a larger beautification project for the area between the old bus stop and the former site of the jail. Funding will partly come from hospitality tax money, but Batesburg-Leesville is also seeking state and federal funding that can offset the cost, Luckadoo said.

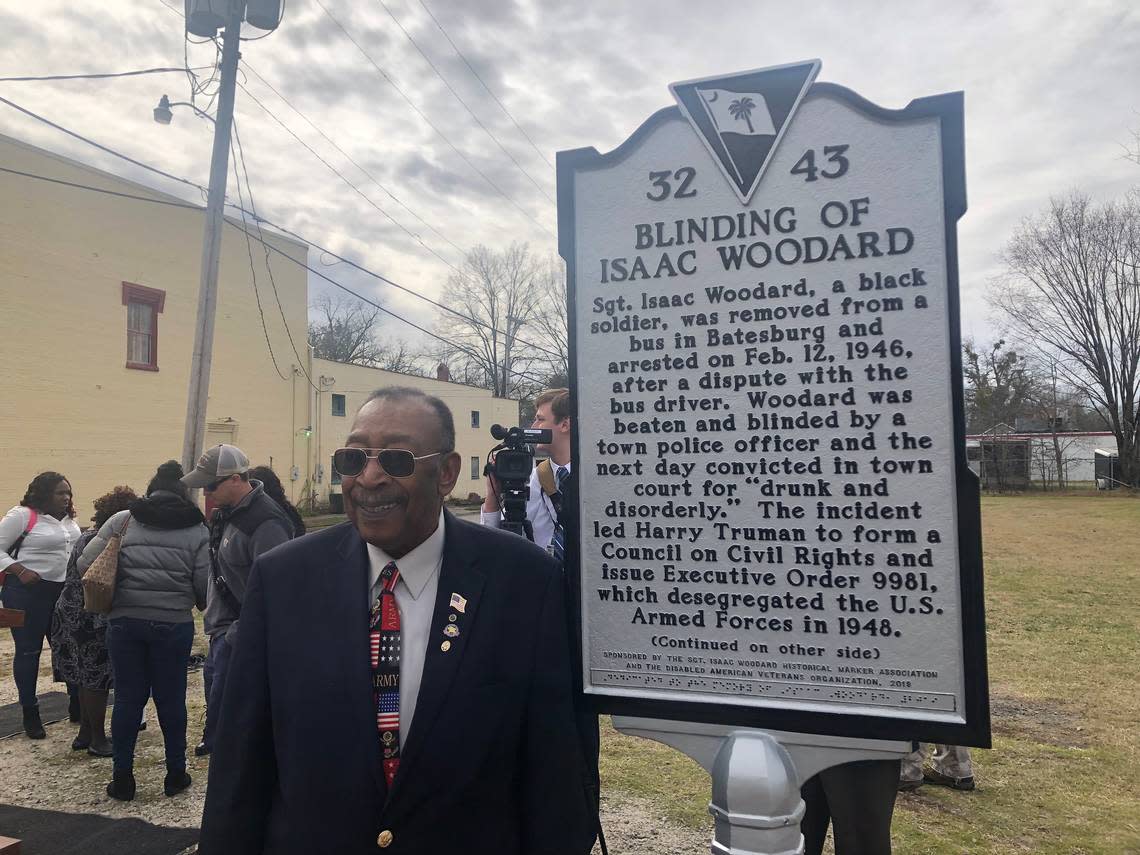

It’s not the first time Batesburg-Leesville has recognized its place in Woodard’s story. In 2019, the town unveiled a memorial plaque to Woodard near the site of the proposed park. But acknowledging this local history has not always been common.

“I didn’t know about it. A lot of people didn’t know about it,” Shull said, crediting Gergel’s book with leading him to learn about the case. “This was a story told in the Black community, but not in the white community. It was swept under the rug. And if you forget the past, then that history is bound to repeat itself. It’s good for everybody to know that those things did happen.”

Gergel’s investigation led the town to overturn Woodard’s conviction for disorderly conduct in 2018. Shull hopes the town of 5,000 can provide an example for how other communities can address their own histories from the civil rights era.

“This wasn’t the only place something like this happened,” Shull said. “It serves as an example of healing as best you can.”