Places hardest hit in Eastern Ky. floods were already losing population. Will it get worse?

The numbers weren’t good in the first place.

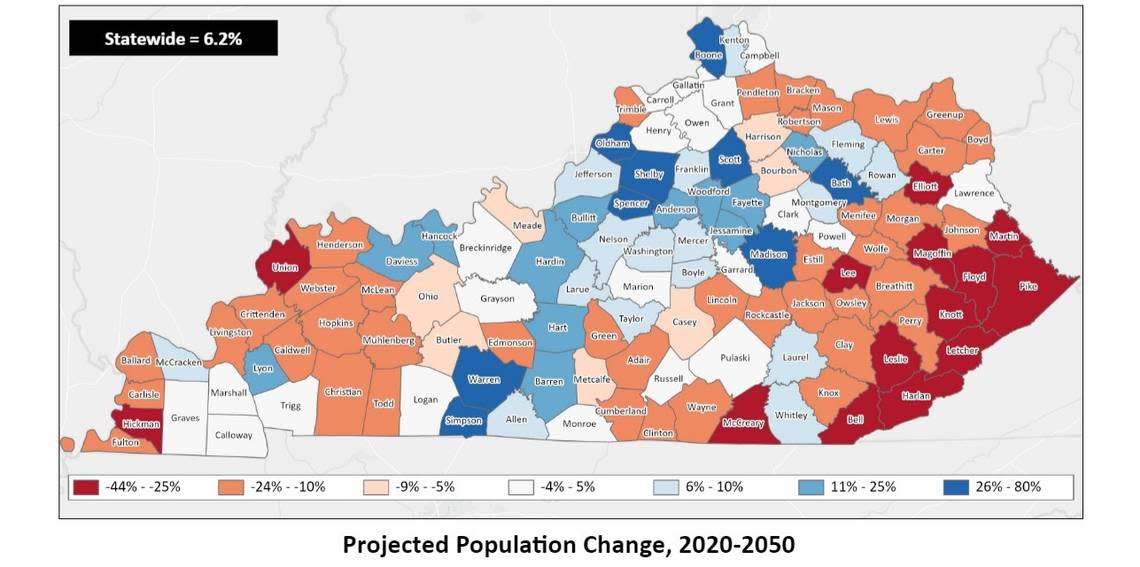

Knott County and Letcher County, both in Eastern Kentucky, are both expected to lose more than 43% of their population in the next 30 years, based on projections from the University of Louisville State Data Center. Those are the two highest rates of any county in Kentucky.

They’re also two of the counties hardest hit by historic flooding in Eastern Kentucky, which cost 39 lives and countless structures. That has some worried that the projections could get even worse.

Valerie Horn, director of the children and families-oriented nonprofit Cowan Community Action Group, said that she’s already seen people leave Letcher County because of the floods.

“Housing was already a problem in Letcher County before this crisis, and is much much more serious now…. If people were on the fence about whether they could make a life here or move away, I think this has been the deciding factor,” Horn said.

Housing was perhaps the hottest topic during the state legislature’s recent special session thanks to Sen. Brandon Smith, R-Hazard, who represents much of the area most affected by the floods. Smith filed a late-session amendment that would have added $50 million in housing-specific dollars to the $213 million flood relief package passed by the legislature; it was rendered out of order by a wording change to the bill, with legislative leaders and Gov. Andy Beshear saying that there was enough in the bill to address the issue in the short-term. Later, a gift of 300 travel trailers from the state of Louisiana was announced to help house displaced families.

When he filed the amendment, Smith warned that without more housing assistance the region could see “the largest out-migration in the history of Appalachia.”

That’s a bold projection given that neighboring counties like Knott and Letcher – fellow Eastern Kentucky counties Martin, Pike and Magoffin round out the top five in projected depopulation – have long been bleeding population.

Why is Eastern Ky. losing people?

Why has much of Eastern Kentucky been losing population?

Housing is one problem the floods have highlighted, but residents across the region say there are several others.

The reliance on coal for jobs, and the subsequent dwindling of that industry, is the primary reason residents say people have moved out of Eastern Kentucky.

The numbers bear that out.

Look at most coal counties in Eastern Kentucky’s U.S. Census population numbers over the years and you’ll see the same story: after a peak in the 1980 census, population numbers have been declining either slowly or precipitously over the past 50 years.

Letcher County has lost nearly a third of its 1980 population, down to 21,548 from 30,700. Harlan County’s figures are even worse, down from 41,889 to 26,831.

The 13 counties eligible for individual and public assistance from the FEMA disaster declaration – including Knott, Breathitt, Perry, Floyd and Pike, which were all hit hard – saw their populations drop an average of 20.8% from 1980 to 2020.

Recent migration trends point to movement as one of the primary drivers of population loss, according to Matt Ruther, Director of the Kentucky State Data Center and professor of urban and public affairs at the University of Louisville. Ruther said the center used data recording life expectancy, fertility and migration to augment its projections based on overall population numbers provided by census data.

According to their estimates, out-migration and an aging population will fuel continued population loss in places like Martin County. There, the center estimates that nearly eight out of 100 Martin Countians moved out in just a five-year time frame from 2015 to 2019.

That’s the case for several of Martin County Judge-Executive Colby Kirk’s friends and family. He says that out-migration is fueled by both material conditions and perceptions of the region.

Kirk, who at 29 years old is one of the youngest county judge-executives in Kentucky, said that he never realized that communities like Martin County were looked down upon by others until the release of Diane Sawyer’s “Hidden America: Children of the Mountains,” a television documentary series that received some sharp criticism for its depiction of Appalachia that some called stereotypical.

“I didn’t know what I could do to change it, but I knew that things weren’t gonna change back here unless young people come home and try to make a difference here,” Kirk said. “I don’t think your zip code should determine your future.”

He joked that he didn’t want his memoir to be titled “the last judge of Martin County,” so he and others in county government have focused on revitalizing downtown Inez, the county seat; making postsecondary classes available in the county; among other initiatives.

The projections for Eastern Kentucky’s population in the next thirty years aren’t generally positive, Ruther said, because the population is weighted towards the baby boomer generation, those born between the mid-1940s and the mid-1960s.

“You had this, this giant population, right? And this bulge, now, is hitting the high mortality years. The youngest boomers are still in their 50s, and so for the next 20 to 30 years, we’re going to see this big bulge (decrease),” Ruther said.

In the four counties where people died from flood damage – Knott, Breathitt, Letcher and Clay – the most populous age groups are people in their 60s or late 50s. In Scott County, Kentucky’s fastest growing county, the largest age groups are children and people in their 40s.

‘I want to be closer to the mountains’

Michael Frazier, a lobbyist in Frankfort who lives in his native Powell County at the Western edge of the Appalachian region said that promises of renewed opportunity – something politicians have been promising for the region since Lyndon B. Johnson launched his Great Society’s “War on Poverty” – that don’t materialize are part of the problem. They’re too frequent in Eastern Kentucky, and can breed distrust in outside interest or investment, he said.

“Frankly, we’ve had too many people come here and give false promises, so it’s not just about creating opportunity, it’s about creating security,” Frazier said.

Opportunity and financial security were reasons listed by Jennifer Disney, a 48-year-old mother of two, for moving her family from Harlan to a suburb of Nashville, Tennessee.

Disney – whose father-in-law, father and both grandfathers were coal miners – said that she had seen her family struggle with coal-related lung issues and she and her husband didn’t want to risk joining the industry, which was still a major regional employer in the late 1990s.

After her husband went to trade school to become a machinist, they realized there weren’t particularly good jobs for him there. So they moved to the Nashville area, which Disney said was “all opportunity.”

But even though their new region hosts a more thriving economy, Appalachia still beckons them home.

“I told my husband when we were home for my dad’s funeral back in July, ‘I don’t want to die in Middle Tennessee.’ I want to be closer to the mountains.”

Colby Hall, executive director at SOAR (Saving Our Appalachian Region) based in Pikeville, argued that it’s one thing to look at population totals, but it would be another, much more helpful proposition to know where young talented people are leaving for and why.

Hall said that if leaders are serious about solving the depopulation issue, then they’ll work to try and track outcomes for the youth in the community.

“Take a local high school class, what percentage of them live in your community now and how many of them are gone? From a depopulation standpoint, that’s a ton of water that’s leaking out of the back of the bathtub,” Hall said.

The flood effect

Some, like Horn, think the problem will get worse because of the floods.

Jeffery Justice is the executive director of the Pine Mountain Partnership, a nonprofit formed just this March to help spur economic development to Letcher County and three of its cities, including Whitesburg.

He said more than 2,000 FEMA claims have been filed in the county regarding flood damage to homes or property. Justice’s organization had already identified housing – much of the current stock in Letcher County dates back to the 1940s or ‘50s, he said – as an issue to tackle.

“Our housing stock wasn’t plentiful to begin with. Now, a lot of available housing was flooded and that will hinder our ability to recruit or keep our population,” Justice said.

According to figures from the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky, more than 5,800 applications have been submitted across the region reporting total or partial home loss.

But Ben Hale, who previously served as Floyd County judge-executive and just retired as the leader of the Big Sandy Area Development District (ADD), thinks that those impacted by the floods aren’t the same kinds of people who were out-migrating in the first place, and that the projections for the region could be overly negative.

Hale said it may not apply to everyone, but in his estimation the ones most affected by the floods were people most likely to stay. “That’s their land, that’s their home and that’s their heritage,” he said.

“When you’re talking about people affected by this flash flooding, we have a culture here in EKY of ‘we like our area. We like growing up, living here, and retiring here.’ With the outmigration, we lost population – but I think that has a lot to do with losing coal jobs around 2012,” Hale said.

Hale’s Big Sandy ADD – which includes Pike, Martin, Magoffin, Floyd and Johnson counties – lost 9% of its population from 2010 to 2020, and the University of Louisville State Data Center estimates that it will fall from roughly 140,000 to 90,000 by 2050.

Where to go from here?

Even from 2010 to 2020, when the continued decline of the coal economy spurred more out-migration, there are silver linings to Eastern Kentucky’s population trend.

A handful of the marquee cities in the region saw fast growth. Hazard grew by more than 18% and Pikeville by more than 12%, though their counties shrunk in population – Pike County moreso than Perry County.

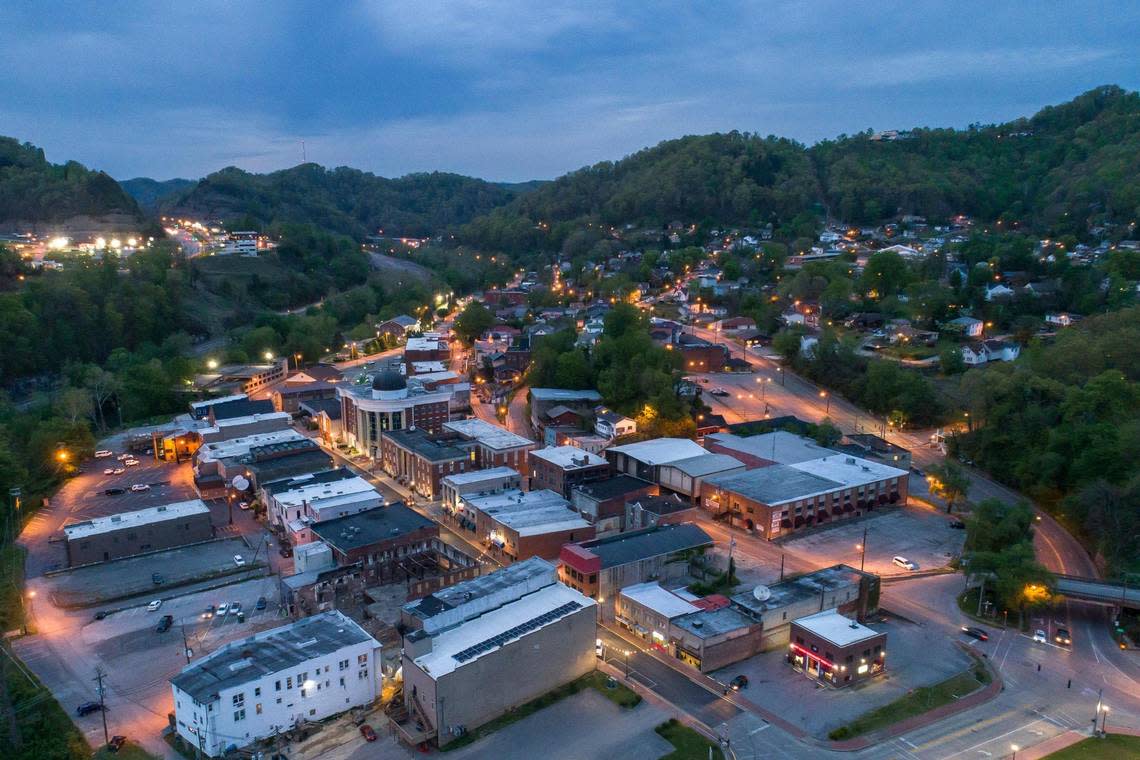

So what worked in these cities? A part of the solution in Hazard, according to city councilman Luke Glaser, is a focus on downtown.

More than 40 businesses have opened there since 2018, and only two have since closed, Glaser said.

A thriving downtown helps in a few key ways, Glaser said: it increases quality of life, it provides some jobs, and it leaves a good impression on potential high-volume employers scouting the area.

“When (factory owners) come here to view our community, the first place a lot of them will go is downtown. In 2015, when the Grand Hotel burned down, there was one bar downtown and a couple of law offices. That was about it. Now you’ve got a coffee shop, you’ve got a toy store, you have an apparel shop, a couple of lunch counters, an arts center – that’s part of the story that they’re gonna see when they come down here to visit us,” Glaser said.

Whitesburg’s downtown is already somewhat renowned for its cultural significance, and Justice said that even though the downtown got flooded this time around, the rarity leads many in the community to believe that rebuilding in the same place with some mitigation strategies in mind is the right move. The National Weather Service has called what Whitesburg experienced a “1,000-year flood,” but climate change has some worried that such events could become more frequent.

“The people here are willing to take the chance to save their town,” Justice said.

Mandi Sheffel, who owns the bookstore Read Spotted Newt in downtown Hazard, said that she previously witnessed an economic development focus on bringing big box stores to the outskirts of town as the downtown dwindled. It didn’t work, she said.

“When we look at bringing industry in, we have to have communities able to uphold that industry… We need to focus inward, and then work out,” Sheffel said.

She added that there’s still a culture of seeing those who ‘get out’ as somehow succeeding more than those who stay.

“It is our job to convince kids that this is a place worth coming back to,” Glaser said. “‘Go get your education, go learn and then come back here to help us create opportunity,’ right? If they see a coffee shop opening in their downtown, and we have a music festival downtown that they come to, they’re more inclined to see this as a place where cool things are happening.”

For others, the main concern is getting the infrastructure needed to attract population – two problem areas worth tackling are water and broadband internet.

Kirk said that in Martin County he’s looking forward to a potential partnership with entrepreneur Elon Musk’s Starlink, a satellite internet constellation, to provide broadband to the southern part of the county. The county’s well-documented beleaguered water system – though Kirk himself said he drinks the water – is also of major importance and could cost millions in the next decade, he said.

Hale said that potable water, brought in by systems that are trusted by industry and residents, is a key part of retaining and recruiting population to the area.

Culture and narratives also play a major role in addressing depopulation, many said.

Frazier, who is gay, thinks that out-migration for the LGBTQ population is a real problem in Eastern Kentucky because of real and perceived biases against queer people.

“Growing up, I never saw people that were like me and respected in the community,” Frazier said.

Frazier, who holds a leadership post in the Kentucky Young Republican Federation, added that he chose to remain in Appalachia after he learned of a gay teenager in his community taking their own life due to bullying. He wants to break the stereotype about the region, and become someone that other members of the LGBTQ community in Eastern Kentucky can look up to at home instead of leaving for greener, or more accepting, pastures.

Another potential solution to Eastern Kentucky’s depopulation problem: immigrants.

Ruther said immigration is the primary reason America is growing relative to its similarly developed peers.

“If Eastern Kentucky had a sudden influx of immigrants – immigrants tend to be younger, and in particular Hispanic immigrants tend to have larger families – that would be one way that this could turn around,” Ruther said.

Glaser, a teacher who came to Hazard via the Teach for America program with the intention of leaving after two years for law school, has stayed for 10 years in part to join the fight against students leaving.

Though he teaches math, he’s baked into his curriculum a practical answer to the proverbial math student question: when am I ever going to use this?

“My theory is, if we’re going to train kids to solve math problems we should also use that same problem-solving model to confront real world problems,” Glaser said. “My kids will read articles and watch film and discuss cartoons or photography about Eastern Kentucky. A lot of them don’t necessarily realize that people from outside this area treat it as an ‘other.’ We talk about a why and how we can push back against that narrative with our own life and work.”

The city government, he said, has helped address the issue as well by creating an internship program for young people to get a feel for how local government can address some of the same issues that Glaser’s class discusses.

Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky Executive Director Gerry Roll said that right now her nonprofit’s primary focus is on getting people who are displaced – for many of them, she said, staying in the area is their only option – in housing.

Justice feels confident that those who do choose stay will end up “better on the other side.”

“If someone’s home is completely destroyed, they got to do what’s best for their family. I understand that. For the people that can and are willing to dig in with us and hold on through the recovery phase, there’s no question, there’s no other option, we’re definitely going to be better on the other side.”