Pierre McGowan: A South Carolina Lowcountry life that cannot be repeated

I always thought that when Pierre McGowan left us, we should latch the screen door of the South Carolina Lowcountry and tack up a note: “Closed. That was just a dream.”

The old cuss from St. Helena Island died the day after Christmas, six days after he was born on his mother’s birthday 96 years ago.

That means it’s 96 years exactly since the day of his first boat ride.

Pierre Noel McGowan’s French mother, born Henriette Vurpillot but called Nancy by her three sons, brought him by steamer from Savannah to their Sears and Roebuck home on St. Helena Island. She often said he’d been in the river ever since.

He was 6 when he took his first trip down the river with his father. He was invited to the rustic campsite on a barrier island because his father, the “Gullah Mailman” Sam McGowan, couldn’t cook and Pierre could.

His father delivered mail from the Frogmore Post Office each morning, then made his biggest decision of the day: to go hunting or go fishing.

In those days, St. Helena was home to some 5,000 Gullah and 65 whites. It did not yet have access by bridge. Pierre grew up bilingual, and as an adult wanted to write a column for the paper in Gullah.

Pierre graduated from The Citadel and fell into the briar patch when his career as a civil engineer enabled him to stay in Beaufort, unlike others in his Beaufort High School class of 1943.

He left us the story of his rare time — actually many stories — in two books: “The Gullah Mailman,” illustrated by Nancy Ricker Rhett, and “Tales of the Barrier Islands.”

That was the real Lowcountry, when the tides, moon, wind, maybe even voodoo — not GPS — guided life. It was when most things were harvested, bartered, recycled, or all of the above.

It was when people appreciated their world for what it was, not for what they thought things ought to be “down here.”

SOUTHERN LIVING

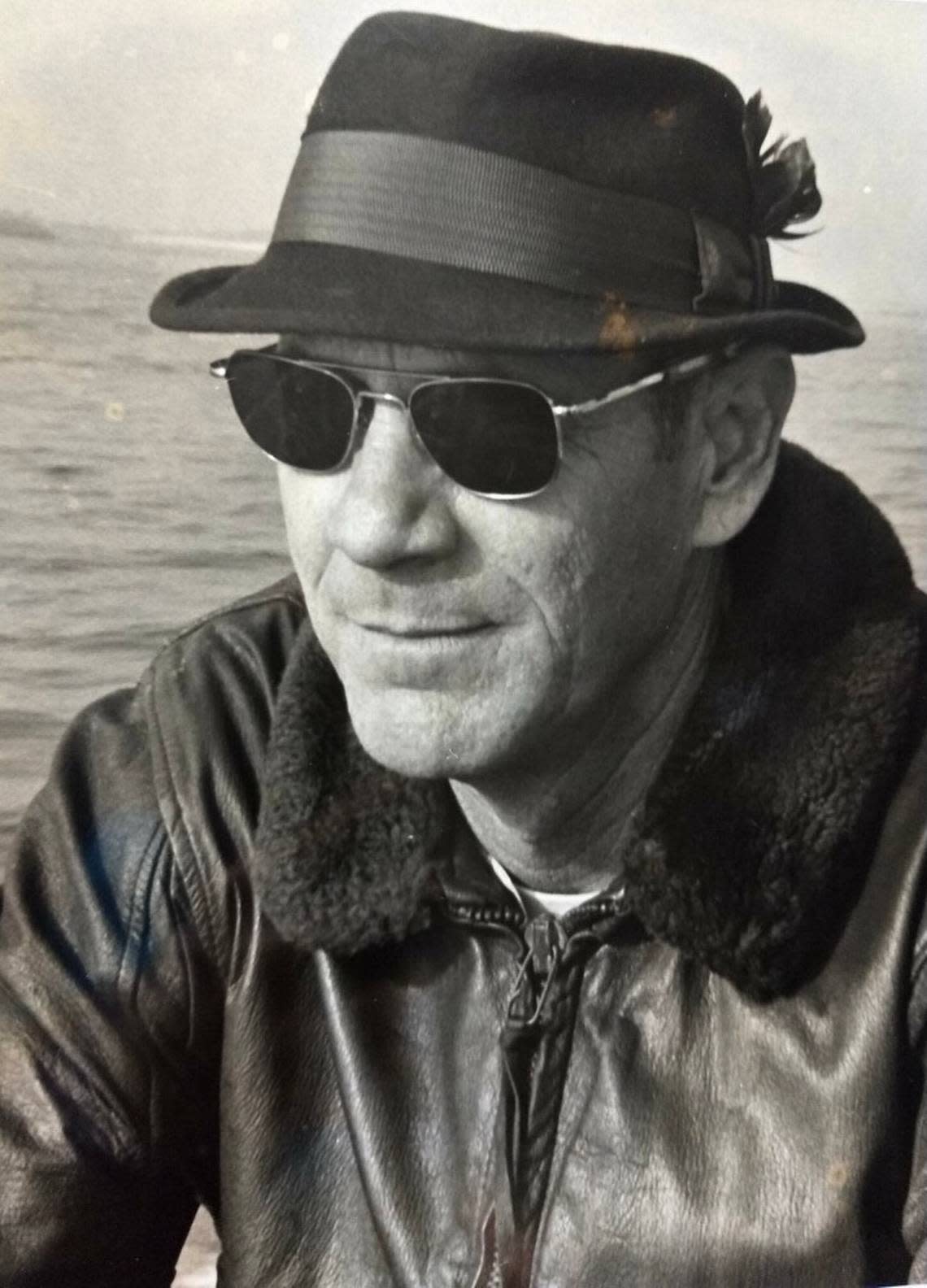

Pierre was a thin man, taut as rope in neat blue jeans or khaki pants and a plaid shirt, his Jack Russell terrier named Junya glued to him as he cruised St. Helena in his little Nissan pickup.

A tape of Handel’s “Messiah” might be playing if it was the season for the choir at First Presbyterian Church to sing it for the faithful.

He could tell at least one story for each home, cemetery or even plant you passed along the way.

When “Southern Living” wrote a blurb about his second book (“In addition to amusing accounts of hunting and fishing exploits, the new book warrants a read if only for its tips on campfire cuisine”), Pierre dropped by to see Beaufort Gazette editor Jim Cato.

Cato quipped in a column that if you let Pierre talk long enough, you wouldn’t have to buy the book.

Pierre liked to puncture his verbal tales with random questions. Like the time he was showing me the causeway he’d built by hand to get to a small island where he spent five years building a home by himself, by hand.

The causeway was made with discarded materials held together by the deep roots of tamarisk shrubs, not bought but rooted one clipping at a time.

“Do you know how the Egyptians built the Great Pyramid?” Pierre asked.

“They did a little bit every day.”

NATURAL HISTORY

Pierre had an engineer’s mind, stuffed with the measurable marvels of nature.

He built a place for osprey to nest in the marsh outside his home, so he could count how many times the adults fed each other, and the babies.

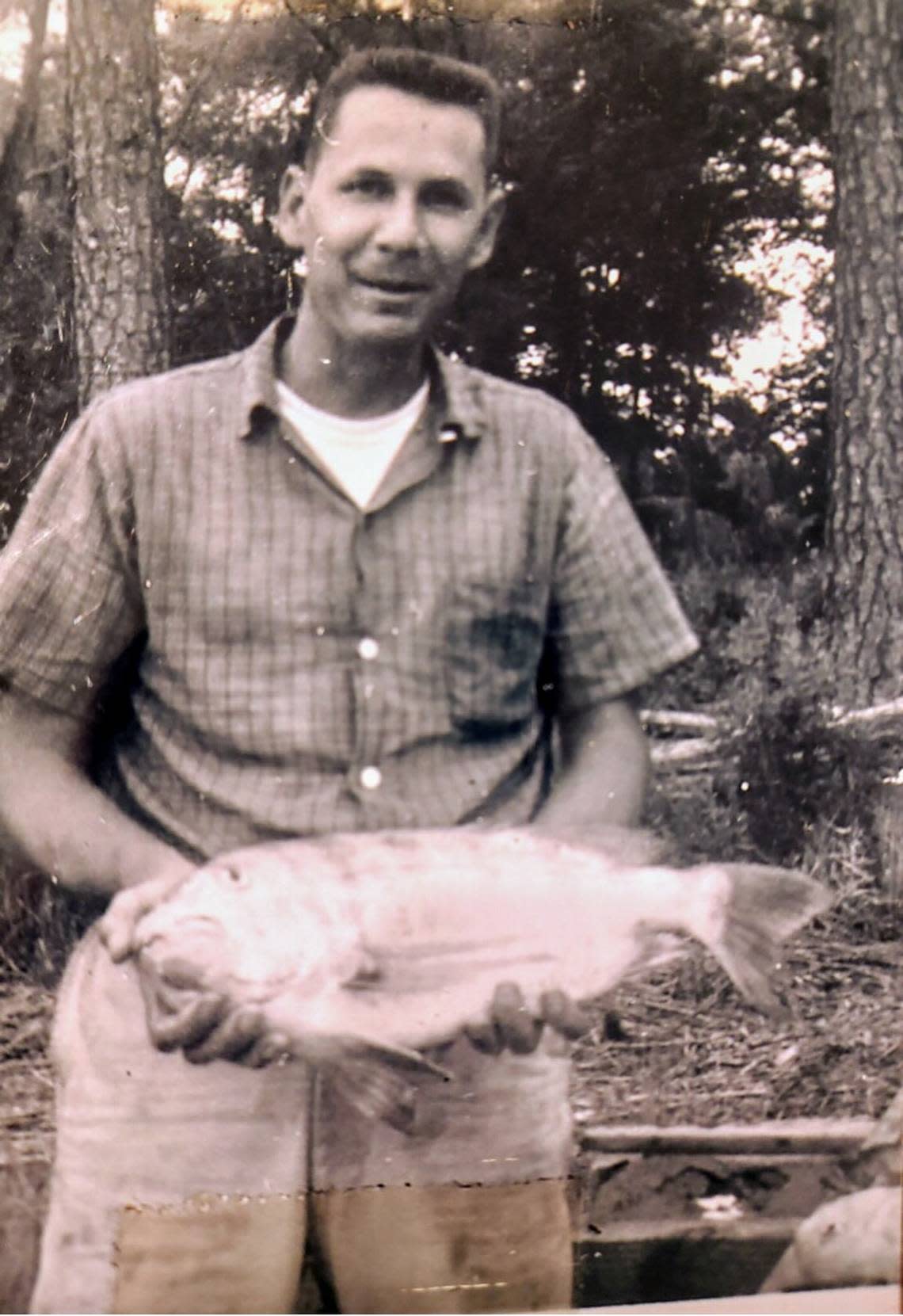

He was proud to have gigged all the flounder for his church’s annual fish fry for more than 15 years. Giggin’ turned him into a Lowcountry gondolier, poised to spear a flounder in the salty predawn hours, a sandy bottom lit by two 110-volt lights housed in an old Beaufort street lamp.

He was well past 90 when he rebuilt by hand his long dock.

He called “going down the river” an addiction. He built a campsite for those weekend forays in the wild on barrier islands with his father in the 1940s, and another with his son more than half a century later.

He traded a pickup truck full of tin to St. Helena folk artist Sam Doyle for a commissioned painting of his father delivering mail in a Model T.

He loved history. He, I suppose, actually paid for an ad in The Gazette to urge people to vote “no” on a referendum on changing the name of his father’s post office from “Frogmore” to “St. Helena Island Post Office.” He lost that fight.

And nobody paid attention when he said the new Spanish Moss Trail should have “Magnolia” in its name when it was converted to a rail trail over the “Magnolia Line” that he rode coming home from service in the U.S. Navy.

He said he missed seeing Gullah fishing and gigging in the river. He said he missed seeing mullet drying on the hot tin roofs of Seaside Road.

He missed the quail that he said once numbered 500 coveys on St. Helena. He thought a major cause of their demise was the fire ant.

He recorded in his second book a long list of the plants and birds he’d seen in his time.

He was a blood donor, a past chairman of the H.E.L.P. of Beaufort social services agency, and an elder at First Presbyterian Church before he joined a group that left and started First Scots Independent Presbyterian Church after falling out with changes in the denomination.

Pierre and his late wife, Faye, reared four children in Beaufort.

And when a nonprofit staged a fundraising comedy called “Murder Gras” featuring three locals, Pierre was one of them. They were called “representative of Beaufort itself.”

Maybe the note we tack to the closed screen door of the Lowcountry should be what Pierre wrote to me in one of his books:

“The stories and times depicted herein are all gone, due primarily to the second coming of the white man.”

David Lauderdale can be reached at LauderdaleColumn@gmail.com.