Pharma-Friendly Democrat Kurt Schrader Has A Progressive Primary Challenger

The progressive insurgency that toppled many prominent blue-state Democrats is now coming for one of Big Pharma’s closest allies in the House: Rep. Kurt Schrader (D).

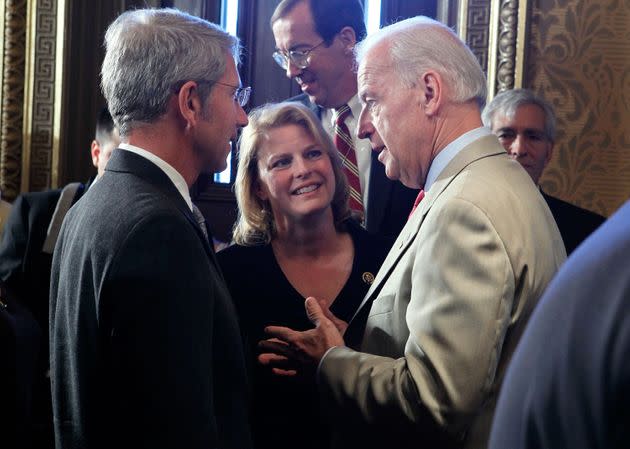

Schrader, a veterinarian and the House’s 11th-biggest recipient of donations from pharmaceutical industry PACs, elicited the left’s ire for his initial opposition to President Joe Biden and congressional leadership’s plan to empower Medicare to negotiate lower prescription drug prices.

It’s one of several ways that Schrader, who has long been on the conservative side of his party’s caucus in the House, has become one of the Biden administration’s most prominent intra-party antagonists.

Now Schrader’s more liberal constituents will have a chance to voice their discontent at the ballot box. Jamie McLeod-Skinner, a school board member and attorney in central Oregon, announced in late October that she plans to challenge Schrader in the interest of sending both a Biden ally and a genuine progressive to Washington.

“This is a really challenging time for Oregonians, but really for all Americans,” McLeod-Skinner told HuffPost in an interview. “My primary opponent is undermining an agenda intended to help us recover from the COVID economy and help our country get back on its feet.”

“I’ll definitely run to the left of him,” she added. “But Kurt has become so conservative that running to the left of him just means you’re a Democrat.”

Schrader rejects the notion that he has obstructed Biden’s agenda, pointing to his support for the version of the Build Back Better Act that passed the House with new prescription drug regulations.

“I’ve been a leader in Congress for years to lower drug costs for all Oregonians, especially our seniors,” Schrader said in a statement to HuffPost. “I led the tough negotiations to successfully incorporate my prescription drug price reduction plan into the Build Back Better Act which would be the most significant improvement in reducing drug costs since the inception of Medicare Part D 15 years ago. I also secured a cap on seniors’ out-of-pocket costs to $2,000 per year, a $35 cap on insulin per month and gave Medicare the ability to negotiate.”

I’ll definitely run to the left of him. But Kurt has become so conservative that running to the left of him just means you’re a Democrat.Jamie McLeod-Skinner

Schrader, whose grandfather bequeathed him a fortune amassed at Pfizer, omitted the fact that he was in a position to negotiate the prescription drug price reductions in the Build Back Better Act precisely because he was one of a handful of Democrats opposed to more comprehensive reforms. Against the objections of Schrader and others, Biden and Democratic leaders wanted to empower Medicare to negotiate lower prices for more drugs than the law ultimately allowed, and with stronger recourse if pharmaceutical companies didn’t bargain in good faith.

To those who question whether the campaign contributions he receives from the pharmaceutical industry have influenced his lawmaking, Schrader said he supports changing the Constitution to limit the influence of outside spending.

“I have introduced a constitutional amendment every year since 2010 to overturn Citizen United to get big money out of politics,” he said.

Overturning the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision would do nothing, on its own, to make Schrader’s reliance on pharmaceutical industry cash illegal.

As is true across the country, the politics of Oregon’s 5th Congressional District, now a general-election swing seat, are regionally specific. The seat, which once stretched from Portland’s outer suburbs into central Oregon, now veers further east and is ever so slightly less Democratic than it was before redistricting this year.

McLeod-Skinner faces an uphill battle, both in unseating Schrader — a seven-term incumbent — in the May 2022 primary, and in staving off a Republican takeover in November, which is expected to be a banner election for the GOP.

Still, the race is likely to have national ripple effects one way or another. A strong showing from McLeod-Skinner would signify that there are political costs for a Democrat willing to cross the party’s president. If Schrader routs her, by contrast, it would indicate that even in a liberal state like Oregon, Democrats continue to prioritize electability and familiarity over other concerns.

“The primarying from the left is about how to make government work for more people and that is a very popular kind of stance in states like Oregon,” said Christopher Nichols, an Oregon State University historian who closely watches Oregon politics. “If the primary, or the election itself, pivots on if Schrader has been a good friend to Biden and the Biden administration, that will benefit whoever his opponents are.”

Avoiding Progressive ‘Buzzwords’

Progressive primary challenges tend to follow a specific pattern. A more left-leaning Democrat tries to oust a more moderate incumbent on the grounds that a solid Democratic district deserves a more forward-thinking, more ethical, and less complacent representative in Washington. Often, though not always, the challenger is younger than the incumbent and from a historically marginalized community, while the incumbent is not.

In some ways, McLeod-Skinner resembles these candidates. She counts her election to the Jefferson County school board as the first instance of an open lesbian winning elected office east of Oregon’s Cascade mountain range, which divides the state’s ultra-liberal northwest from the rural and conservative central and eastern regions.

And McLeod-Skinner backs the now-standard list of ambitious, social-democratic policy goals that have become a litmus test for candidates seeking the blessing of the activist left. She supports a “Medicare for All” single-payer health care system, the adoption of a $15 minimum wage at the federal level, and a Green New Deal to transform the United States’ energy infrastructure.

Where McLeod-Skinner differs from some progressives is in her belief that the left is failing to effectively communicate with rural Americans.

“The pitfall has been grabbing onto buzzwords and not just focusing on ideas,” McLeod-Skinner said. “I wish you could have been there with me for some of the conversations I had in some of the most rural and conservative parts of our state, where the ideas that people are talking about and what people want for their families and their future are what any pundit would call a hardcore progressive idea.”

Rural living is not a flight of fancy for McLeod-Skinner. Raised in southwestern Oregon, she and her wife now live in a modest house on a gravel road in central Oregon’s high-desert region. The couple, which technically lives just outside of Oregon’s 5th, lives with two dogs, numerous chickens, and three goats.

Oregon’s 5th Congressional District has been my home for more than 40 years.Rep. Kurt Schrader (D-Ore.)

McLeod-Skinner is fond of recounting her warm relationship with a next-door neighbor who still flies a Trump flag more than a year after the 2020 election.

On questions like climate action, ensuring universal health care, and making child care and higher education more affordable, McLeod-Skinner is convinced that different kinds of rhetoric are all that’s needed to bring in voters like her neighbor who might otherwise be reluctant to vote for Democrats.

“I don’t believe in spending public money, I believe in investing it,” she said. “When you talk about the ideas of investing in our families and working together to get there, call it what you want, I see it as a path forward and I see it as a solution.”

Occasionally, McLeod-Skinner’s efforts to leapfrog cultural third-rail issues can veer into evasiveness. Pressed repeatedly on whether she supported reductions in funding for traditional policing — the central demand of the “defund the police movement” — McLeod-Skinner refused to answer directly. Specifically, I wanted to know if she supports non-police interventions (like a mental-health emergency pilot program) to replace traditional policing, or to merely supplement it.

“I reject the premise of your question,” she said. “I more broadly define public safety than simply having officers show up in uniform, in a police car, responding to calls. It’s community engagement. It’s community relationships.”

Fighting For Rural Votes

McLeod-Skinner, who uses her law degree to run a policy consulting business, does not have the slick presentation of a politician born to speak at a lectern. She is earnest and mild-mannered, speaking matter-of-factly about the need for commonsense policies aimed at curbing wildfires and expanding health care access.

What she lacks in dazzle, she makes up for with a record of punching above her weight in rural parts of the state. With a much smaller campaign war chest, McLeod-Skinner received a respectable 39% of the vote in her 2018 run against Rep. Greg Walden, a prominent Republican representing Oregon’s solidly conservative eastern regions. Hillary Clinton got just 36% of the vote in Walden’s district in 2016.

Several of the more Democratic parts of Walden’s district that she won, such as the increasingly liberal city of Bend, are now in Oregon’s 5th.

“Her strong advantage is that she is known in and around central Oregon,” said Judy Stiegler, a former Democratic state representative from Bend who teaches political science at Oregon State University, Cascades. “She has proven herself with a growing Democratic electorate over in this part of the state.”

McLeod-Skinner’s 2020 run for secretary of state was less competitive. She came in third place in the primary, receiving 28% of the vote in a three-way race where the winner got 36%. She nonetheless carried Deschutes County, which is home to Bend, by a wide margin.

McLeod-Skinner has since burnished her credentials in a rural corner of southwest Oregon, completing a stint as interim city manager for the municipality of Talent. This past June, she helped secure the city $1 million in state funds to help with recovery from a major wildfire.

That kind of first-hand experience governing is part of what McLeod-Skinner believes makes her a “pragmatic progressive.”

“I’m progressive in my ideas, but I still want to get them across the finish line,” she said.

Party Loyalty vs. Electability

McLeod-Skinner’s best path to the Democratic nomination is to make the race a referendum on Schrader’s loyalty to Biden and the Democratic Party’s values.

Moderate elected officials often choose to break with their party when the party’s stance is unpopular in their district. Schrader chose to break with Biden on the issue of Medicare prescription drug price negotiation, however, which is extremely popular across the ideological spectrum.

Schrader was also one of two Democrats in the House to vote against Biden’s COVID-19 economic relief legislation, which included $1,400 checks to most American families.

He also raised hackles when he compared the effort to impeach then-President Donald Trump after the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol to a “lynching.” He later apologized for the remarks.

“It isn’t just that he is more moderate, but he has been oppositional” to key elements of the Democratic Party’s agenda, Stiegler said.

Discontent with Schrader’s voting behavior has already helped spark an upswell of significant endorsements for McLeod-Skinner. She has the support of three state senators, three state representatives, a host of local elected officials, and three chapters of the Democratic activist group Indivisible.

I’m progressive in my ideas, but I still want to get them across the finish line.McLeod-Skinner

But Schrader has many advantages over his challenger. He will almost certainly note that unlike McLeod-Skinner, he actually lives in the district.

“Oregon’s 5th Congressional District has been my home for more than 40 years,” he said in a statement to HuffPost. “It is where I proudly raised my family, built my veterinary practice, operated my farm and served my neighbors.”

He is also likely to make the case that he is the more electable candidate in a cycle that is sure to be tough for Democrats. Redistricting reduced the seat’s partisan Democratic lean from D+4 to D+3, according to a metric developed by FiveThirtyEight. How that inside-baseball number plays with voters remains to be seen, but Schrader, who won by just seven points in 2020 in a district Biden won by almost 10, can argue that a more progressive candidate would make victory for Democrats even more difficult. That McLeod-Skinner lost races for secretary of state and for Congress — however strong her performances in central Oregon — only adds weight to that point.

Nichols, the OSU professor, agreed: “‘She’s not a winner’ would be a quick take there that is usually quite effective in Oregon and Democratic politics.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.