Perfection, pain and progress: Inside the 1972 Miami Dolphins’ fight against brain injuries

Matt Morrall did not very much doubt what was happening to his father. Earl Morrall, who started 11 games at quarterback during the perfect 1972 Miami Dolphins season, spent the last final years of his life in deep decline, exhibiting the early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and eventually confined to a wheelchair for his last six months. His son knew football was the culprit.

The highlights the family would play at Morrall’s funeral in 2014 would tell the whole story. He was hit in the head and horse-collar tackled, and always hopped right up to go back into the game. Right around the same time, public understanding of chronic traumatic encephalopothy — better known as CTE — was becoming more widespread and Morrall, as a former offensive lineman for the Florida Gators, naturally took an interest. His father’s symptoms, coupled with the way he played, lined up with expectations for the degenerative brain disease.

PERFECT MEMORIES

Join us each Wednesday as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the perfect 1972 team

In those final days of Morrall’s life, doctors recommended to the family they donate his brain. It has to happen quickly — within 24-48 hours of death — and so Morrall’s brain headed from South Florida to Massachusetts, to the Boston University CTE Center and Brain Bank, to be sliced up and examined for the telling tau proteins, the presence of which would signal the presence of the disease.

About six months later, there was the diagnosis everyone expected: Morrall had CTE. The only surprising part was how severe it was: Stage 4, the most serious of the four stages.

Morrall’s diagnosis became public in 2016, when The New York Times reported it, and soon after his phone rang with a familiar sound on the other end. It was the confident, authoritative voice of Nick Buoniconti, albeit a little bit slower and more deliberate than it once was. He knew Morrall was not alone, and he wanted to tell his former teammate’s son.

“I have the same thing your dad had.”

The 1972 Dolphins’ tragic bond

Buoniconti was right and a diagnosis after his death confirmed it.

In all, there are now six members of those undefeated 1972 Dolphins who have been diagnosed with CTE.

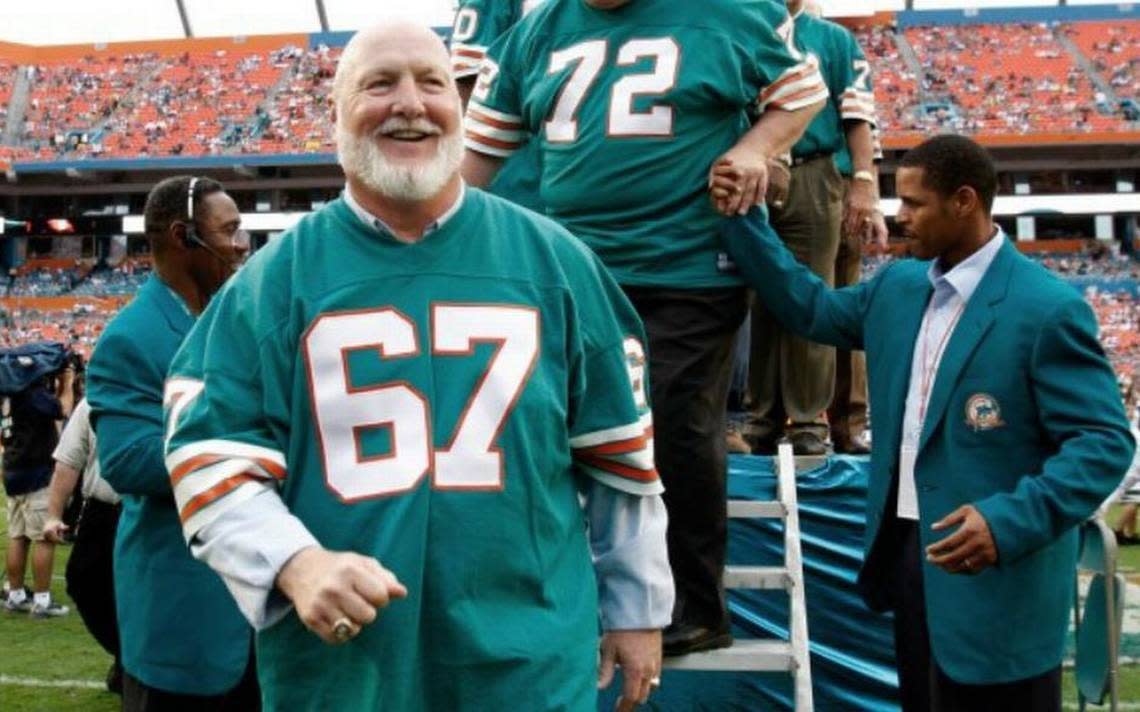

Morrall, Buoniconti, All-Pro defensive end Bill Stanfill, star guard Bob Kuechenberg, All-Pro safety Jake Scott and star running back Jim Kiick all had their brains sent to the Boston University CTE Center — either at their own insistence or the behest of a relative — to be tested for CTE and all six had it.

There are almost certainly more. CTE can only officially be diagnosed posthumously, but living players either suspect they or old teammates have it, too. As far back as 2017, Mike Kolen, Tim Foley and Hubert Ginn were all dealing with cognitive issues, and those same issues added an air of melancholy to a team reunion in Miami Gardens last month.

“I’ve seen guys with CTE,” said Jim Del Gaizo, who was the Dolphins’ third-string quarterback in the 1972 NFL season, “and they don’t know who I am.”

For those six to test positive, the symptoms varied wildly, from memory problems to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and yet they all had similar reasons to want their brains studied, as conversations with relatives of five of the six reveal.

‘There’s something about that team’

The natural first question is, Why this team? Why has this team, the most famous and successful in NFL history, been particularly ravaged by this awful disease.

“There’s something about that team,” Dr. Ann McKee once said and there’s no real way to find a firm answer as to what.

McKee is the director of the Boston CTE Center, which examined the brains of all six former Miami players and found most were dealing with Stage 4 of CTE.

The disease is caused by repeated head injuries and they don’t necessarily have to concussions, although those certainly contribute, too. Subconcussive blows and mild repetitive head impacts — the sort of head-to-head or head-to-shoulder, or head-to-any body part contact that happens on nearly every play — can add up and eventually bring on the disease. It appears roughly 30 percent of the time in those with multiple head injuries, according to a 2017 study by JAMA. The brains of former NFL players in the Brain Bank test positive for CTE more than 90 percent of the time, McKee said.

One suspicion about the Dolphins is the cause might be part of what also made the team so great.

“Those guys played hard. They had a huge team ethic of winning, and you could imagine in that kind of atmosphere that a player would play through any personal, physical pain to continue to bring his team to victory,” McKee said. “I think that occurs in all the teams, but I think that team may have been particularly prone to that, that they had such a team spirit to win that it was almost win at all costs.”

Said Alexandra Kuechenberg, the daughter of Kuechenberg: “He was proud of the way he played. He was proud of sort of giving everything to the game, but in the end I think it was a big contributor to his loss of quality of life.

Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Don Shula, who died in 2020, was notoriously demanding, too, and sometimes would have his teams practice four times per day in training camp. The repeated clicking of helmets, often without any immediate symptoms, never registered as posing any real danger back then.

The simplest explanation, however, might also be the most logical: If any team from the 1970s tested at the rate Miami has, those rosters would probably be filled with CTE cases, too.

“You could probably start looking at any team. ... You’re probably going to find a whole collection of them,” McKee said. “Because it was such a famous team, because they were just extraordinarily successful — there’s always been a lot of attention paid.”

They were famous, and they knew it and loved it, and most knew something was wrong with them. Conversations with those relatives almost always lead to a common idea: This was a smart, thoughtful group of men, many of whom accomplished things away from the field after their playing days were done.

Morrall was a mechanical engineer and the mayor of Davie. Buoniconti was a practicing lawyer, an agent and host of “Inside the NFL” on HBO. Stanfill had a successful career as a real estate broker. Kiick was a private investigator for the Broward County public defenders’ office. Kuechenberg and his wife were so good at flipping houses they eventually had a $3.5 million mansion on Star Island in the 1980s. Scott was one of the NFL’s great one-of-a-kind characters, shunning the post-perfection limelight to live almost off the grid in Hanalei, Hawaii.

“If you look at some of the things they did in later life and how successful they were, it’s an unusual amalgamation of people,” Morrall said. “They were very smart people, and as more and more information came out about this they became aware of this, and the communication level, because of this team [was special].”

When they started to slip or see their friends start to slip, they mostly knew it. Most would admit football played a part.

The Dolphins’ stories of struggle

Allie Kiick was still in high school the first time she remembers her father’s brain starting to fail.

She didn’t have a car and so her father dropped her at Barnes & Noble to get books for school. Her phone was dead and her mother didn’t know where she was. Her father couldn’t remember where she was.

“My mom couldn’t get a hold of me and was calling my dad because she knew that I was with him, and when he picked up the phone and she asked where I was, he said, ‘I don’t know,’” said Kiick, who’s a professional tennis player. “He completely forgot that he had me and had dropped me off.”

In the end, Kiick’s symptoms were some of the worst. He lost most of his abilities to create short-term memories. About a decade ago, Austin Kiick, his son, started to realize he wasn’t taking his medications correctly. The family long balked at putting Kiick into assisted living, but by 2017 they had no choice.

“He was going and getting debit cards all the time from the bank and I guess somebody at the bank said, Listen: Something’s wrong, so the state came in,” Austin Kiick said. “He had congestive heart failure, so he was in the hospital and I guess he was doing some things in the hospital or whatever, and basically, like I said, the state came in and said we can’t release him, discharge him until we know that he’s going to go into assisted living.”

Kiick spent the last few years of his at an assisted-living home in Fort Lauderdale, still regaling people with stories of his playing days, even as the disease progressed.

A few months after the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, Kiick died at 73.

“That’s when I saw him just completely go down the tube. He was so confused. He didn’t want to get up and walk, he didn’t like to eat anymore,” Austin Kiick said. “I just kind of saw him go from an adult back into child mode. ... It just became like I became his father.”

Kuechenberg — who, as a lineman, once quipped, “As long as he’s beating on my head and not the quarterback’s, it’s all right with me” — similarly struggled with memory, made poor financial decisions and was prone to erratic mood swings. He got divorced and rarely left the house.

He died in 2019 at 71.

Stanfill was suffering from dementia when he died in 2016 at 69. Morrall had all the symptoms of Parkinson’s when he died at 79. Even Scott, who outwardly appeared to be in about as good of shape as 75-year-old when he died in 2020, quietly struggled with persistent memory and organizational problems, and displayed early signs of Parkinson’s.

“I took care of all his meds and his doctors appointments,” said Rita Fabal, Scott’s sister. “He liked to cook, and he would call me over and over again for the same recipe.

A ‘pursuit of the truth’

The real question isn’t as to why did all these Dolphins have CTE, but rather, Why have they wanted to have their brains picked apart and studied?

Part of it, undeniably, is out of spite and frustration with the NFL, and its long history of denying the connection between football and CTE.

Buoniconti’s payout from the league was $47,000, his wife said. Scott and his family never saw a penny, denied multiple times when told his symptoms didn’t meet the criteria for a settlement. Kuechenberg didn’t, either. The NFL always denied Morrall payments because he was never officially diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

“The NFL was a nightmare throughout this entire process,” Allie Kiick said.

“He wanted as many results to go in,” said Randy Fabal, Scott’s brother-in-law, “to show what the NFL has done.”

Mostly, these players just want to do some good, however it manifests.

Buoniconti and Scott both decided when they were alive they wanted to have their brains studied. Family made the decision for Morrall, Kuechenberg and Kiick, albeit with the firm belief it’s what they would’ve wanted.

“We thought it was important to get as much information as possible about these types of injuries and to provide this information in the hope of advancing the science, both on preventing it and understanding it a little better,” Morrall said. “Information is power.”

Said Kuechenberg: “His morality was very clear and I think that he would be in pursuit of the truth, so not necessarily wanting consequences or changes based on it, but for people to understand the reality based in science. ... That would be something that he’d want parents to know if their kid is wanting to pursue professional sports. It’s a factor of truth that he would think valuable.”

Although he stayed private for most of his later life, Scott made a point of encouraging any former player he came across to donate his brain. He and Stanfill were roommates when they played for the Georgia Bulldogs, and Rita Fabal remembers Scott rejoicing when he found out Stanfill’s brain was going to be studied.

He never articulated exactly what he hoped would come of it, Fabal said. Scott had his issues with the NFL, but he knew he wasn’t going to get anything out of it. He thought about the future.

“He wanted to see some type of justice,” Rita Fabal said. “I’m not sure what, but he wants everybody to send their brain in. That’s it. It’s sort of the good of the masses. It was really quite worthy of Jake. Jake didn’t really expect anything to be done for him, but when he was having all of these signs and to be told, No, nothing wrong, or, if there was something wrong, it should’ve been manifested earlier … it was a very, very narrow scope.”

An ongoing legacy

Even 50 years after completing the NFL’s only undefeated season, the 1972 Dolphins remain one of the most influential groups of individuals in the modern NFL.

No team has contributed more to the Brain Bank and, because these were players from such an important team, every one of those diagnoses generates headlines across the world. Their donations beget more.

“Because they were so loved,” McKee said, “I think it’s especially poignant.”

Every one of those brains matter because every autopsy is a chance to learn more about the disease and how to best identify it.

The next step in CTE research is to figure out how to diagnose it during life. MRIs can give doctors an idea of whether someone is suffering — the presence of a cave of septum pellicidum in the brain, for example, can be a sign — but nothing from a brain scan so far can be entirely conclusive.

“We’re aiming for diagnosis during life, with the idea that if we can identify it early we have the greatest chance of actually maybe arresting the process or even reversing it,” McKee said. “If we’re able to diagnose it during life, we have potential treatment for tau-based diseases, but we can’t use them in clinical trials until we have a way of monitoring the individuals who are getting the treatment. The next hurdle and the most important hurdle, and why we take in all these brains in the brain bank — what we’re hoping to do is diagnose this disease in the living and that way help living athletes.”

“We see atrophy in different parts of the brain and those things give us a clue, but it’s not total certainty. It could be Alzheimer’s disease that just looks, for some reason, more like CTE in the brain scan.”

At the very least, it would mean the NFL couldn’t deny compensation to players like Scott and Kuechenberg.

“They’re just pushing it, pushing it, pushing it until they die,” Kuechenberg said, “and that’s it.”

For Dolphins, price and perfection

Buoniconti would not have played football — not if he knew what it would do to him in his 70s.

At least, it’s part of what he told SI before he announced plans to donate his brain.

“I would not have played football,” he said, although he contradicted himself elsewhere: “Had I known, would I have played? I had no alternative. There was no other way for me to get a college education. Football kept rewarding me.”

It sums up the dichotomy most of these Dolphins felt.

The natural final question to ask is, Did they regret it?

Football gave them their lives, mostly fabulous. Football took them away.

“I can’t think that I would not have ever played football, given the way I was at 18-21 years old and because there was a lot of joy in playing that game, and it was one of the things that I did that I excelled at,” Morrall said. “Same thing for all these guys, too — it gave them opportunities and took advantage of it, did something special with their lives. Not that many people can say they made the NFL. It’s part of life. Everybody has to make these choices. It’s better to have more information and the more information you have it’ll help with the future of the game.”

Said Allie Kiick: “I do know that my dad would have done it all over again. He 100 percent would have. He’s an athlete and that’s how we are sometimes. We devote our lives to a sport and we’d do it all again, even with the ramifications.”

When he was younger, Kiick would usually try to avoid the constant attention and autograph seeking. It wasn’t the case later on.

“Toward the end, he was the one approaching people,” Austin Kiick said. “I’d have to slow him down. He’d see a guy with a Dolphins hat or shirt, or whatever, and he’s like, Are you a Dolphins fan? Yeah, and then he’d show him his ring, he’d tell him who he was.

“That kind of made me a lot happier, to see that he was just so proud of his accomplishments, so I could never take that away from him. He would do it all over again.”

Said Kuechenberg: “Would he have changed it? No. The type of person he was, he wouldn’t have. He would have still played the game the way he played.”

Her father, she said, was more likely to lament how “they don’t play like they used to” and his frustrations were more about how little the NFL did for the players who gave their body like he did.

Their thoughts, however, cannot change the way some of their loved ones feel.

“I have a little bit of—I hate to use this word, but—hatred to the sport,” Allie Kiick said, “just because I lost my dad way too early.”

“Personally, I find it very hard to watch football because every time I hear the click of the helmets,” Buoniconti said, “I know that someone somewhere is going to end up with CTE.”

Rita Fabal, spent every week this season rooting against the Philadelphia Eagles and celebrated when they lost their first game to the Washington Commanders on Nov. 14.

She still follows football—and, it should be noted, Scott’s symptoms were not quite as severe as some of his former teammates’—and the violent nature of the sport doesn’t detract from her enjoyment.

“I remember Jake,” she said.

The whole family, after all, was there the day Scott grabbed two interceptions in Super Bowl 7 to win the Super Bowl Most Valuable Player Award.

In the madness after the game, Scott found his mother and grabbed her to take her to a party.

“I didn’t bring clothes like that,” she said, as Fabal recalled.

“It doesn’t matter now,” Scott replied. “We’ve made it.”