'Perfect and entire ruin': How Tallahassee survived after 1843 inferno | TLH 200

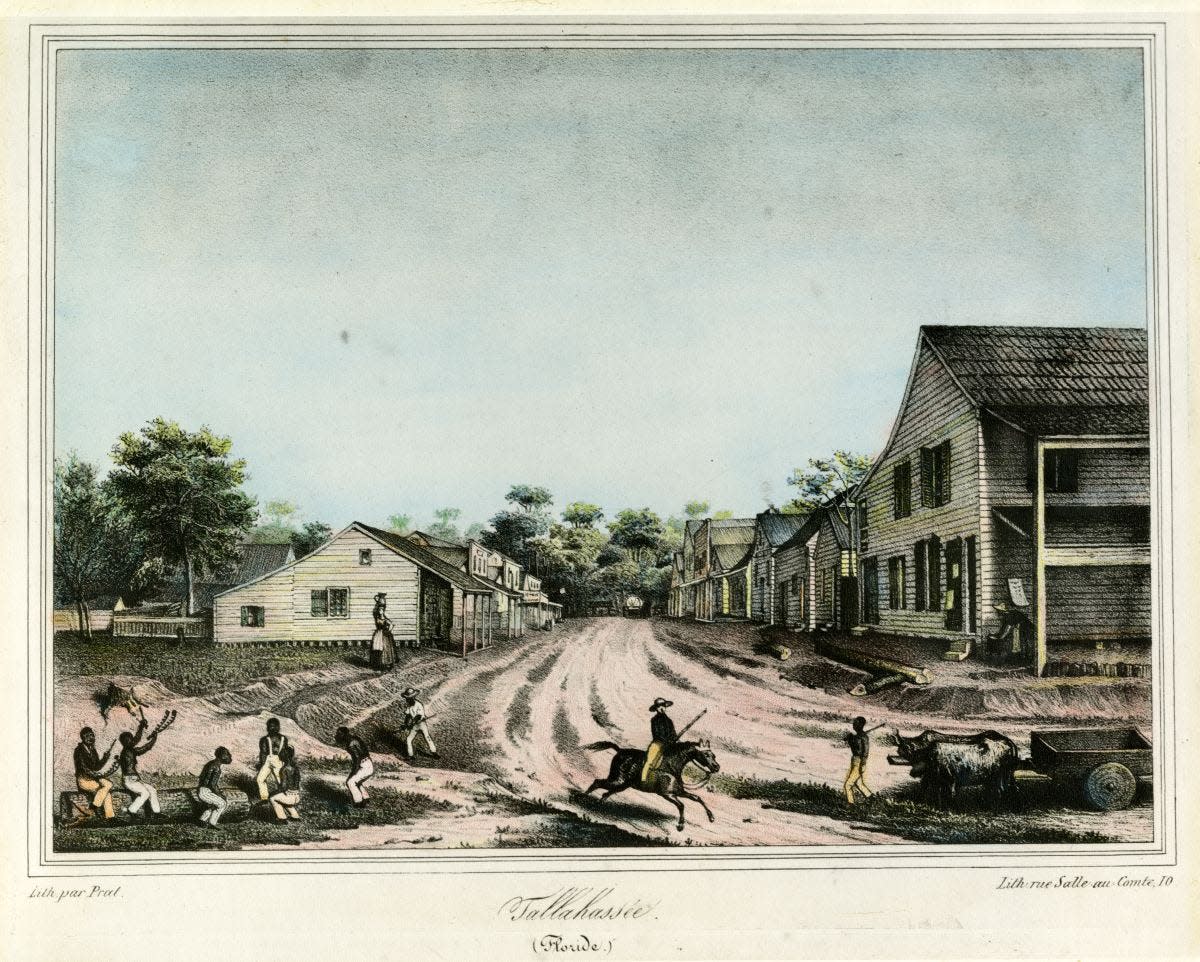

It’s 5 p.m. on May 25, 1843, in Tallahassee. For the next three hours, the city would be engulfed in flames.

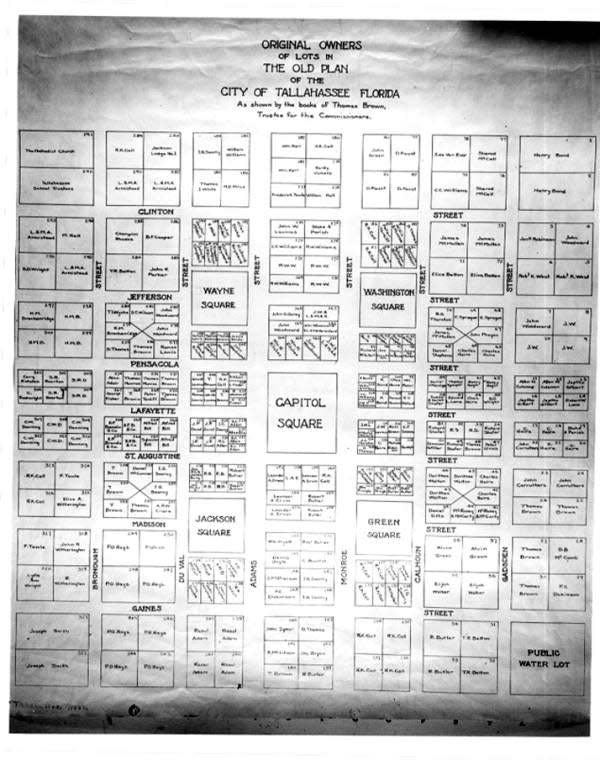

Blocks of downtown were turned to ash as a fire broke out on the grounds of the Washington Hall Hotel, east of the Capitol. For $2 a day, the hotel provided room and board for guests during Florida’s territorial period (1822–1845) and served as a place for civic and religious activities.

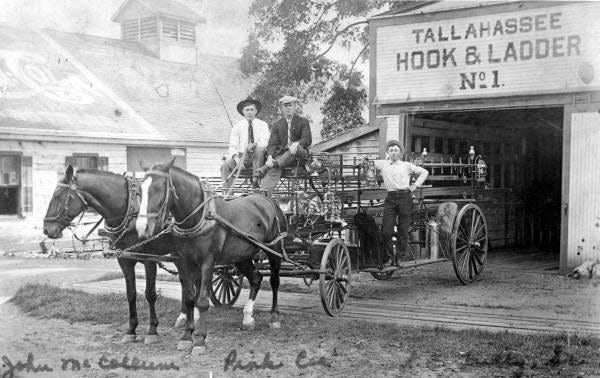

The hotel fire spread north, claiming stores, a blacksmith, numerous homes, offices and other businesses, including those owned by Gov. Richard Keith Call. The courthouse caught fire multiple times but was spared by alert citizens who extinguished the flames. The wooden buildings of the Planter's Hotel, Dorsey’s Auction Room, Perkins Drugstore and the Log Cabin shoe maker’s shop were burned to the ground.

“One of the most sweeping fires that perhaps ever overwhelmed any city with perfect and entire ruin,” according to the May 27 edition of the Star of Florida.

“The terrible element had arisen in its power, and the feeble strength of man was nothing before it,” the article reads.

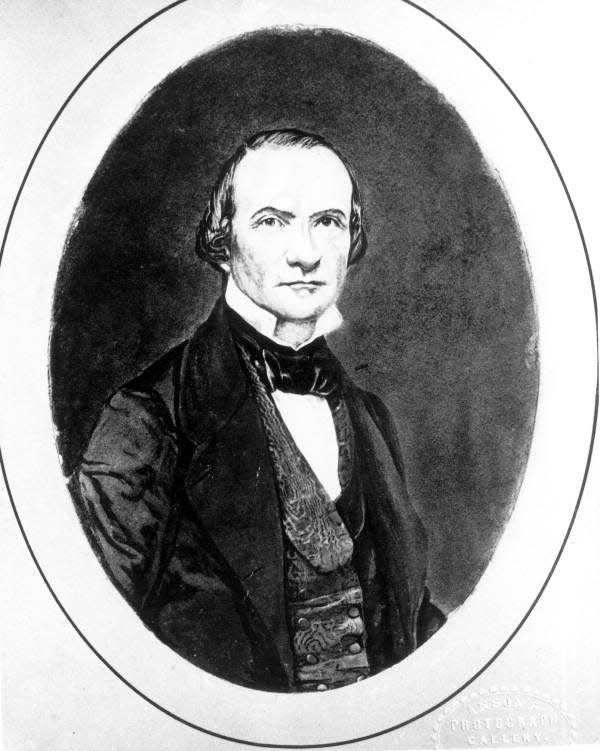

In an editorial in the Florida Sentinel on June 6, Francis Eppes, mayor of Tallahassee at the time, said the city had already started to rebuild and was back in business.

“As gold is tested by the fire, so are the moral qualities of man tried by adversity,” he said. “There is none of that stagnation, idle stupor, hopeless despair, or brooding, listless melancholy which might be expected after the overwhelming blow which has fallen upon our previously embarrassed community.”

Days after the fire, he enacted an ordinance requiring only “fire proof” buildings in the downtown area. Most of the buildings in Tallahassee were made from local timber, most likely pine or cypress, said Sam Wilford, the deputy state archaeologist for the State of Florida.

“Be it ordained ... That it shall be unlawful for any person to build ... any house ... situate within said burnt district ... which shall be composed of wood. That all houses shall have the walls of brick, stone . . . . and the roof of slate, tyle, zinc... ,” the rule stated.

The arson investigation and brutal aftermath of the fire

The damages to the city were estimated to be about $500,000, about $21 million in today’s dollars.

Authorities investigated a disgruntled hotel tenant who allegedly had a disagreement with the owners of the building and who was accused of setting fire to the hotel “in the spirit of vindictive revenge,” Eppes wrote.

The tenant, along with a person employed as a cook at the hotel, were arrested. But neither were found guilty after a court unanimously decided that although the fire was the result of arson, there wasn’t enough evidence to convict anyone of the crime.

It was a double blow to citizens who were lucky enough to survive a yellow fever epidemic that swept through the city and killed entire families.

“Some have lost their all. They rose up that morning in the confidence of wealth – rich in the world’s goods. Before the sun went down, all their earthly possessions had passed away,” the Star of Florida reported in dispatches about the inferno that were published in newspapers around the nation.

“Those who have been spared this trying calamity, should remember their brothers who have fallen under the severity of heaven’s chastisement.”

Eppes stressed the strength of the city’s business owners, who had already dealt with the fluctuating price of cotton in the 1840s combined with the Panic of 1837 that pushed the country into a depression. He noted that business owners "are fast establishing themselves in shanties near their old stamping-ground."

“We doubt if any could have endured a long series of buffetings of fortune with braver hearts than they,” Eppes wrote.

Artifacts tell a story

Today, the Union Bank, which was moved to 219 Apalachee Parkway in 1971, sits on the site where the Washington Hall Hotel used to be.

Many of the artifacts recovered from the Washington Hall fire were preserved in the 1960s, but some were found as recently as 2017.

Plates, bottles, even commodes used at the hotel have been glued back together and sit protected at the Florida Department of State’s archives at Mission San Luis.

Ceramic plates from England that depict the city of Norwich, buried in a cellar outside of where the hotel used to be, were uncovered in the 1960s almost intact, stacked in between sheets of paper.

Wilford doesn’t know why the plates and other china weren’t saved after the fire. But they layers of ash they were found under preserved the dishes for over a century.

“Some of these you could probably eat off today,” he said.

In 2017, city employees alerted the state that they found artifacts outside of the Union Bank. The chips of ceramic plates, pipe stems and oyster shells they collected had evidence that they had once been burned.

“This is a good snapshot of Florida as a territory,” Wilford said. “It gives you the idea of the kind of styles and tastes and choices people are making as they themselves move into the state.”

This story is part of TLH 200: the Gerald Ensley Bicentennial Memorial Project. Throughout our city's 200th birthday, we'll be drawing on the Tallahassee Democrat columnist and historian's research as we re-examine Tallahassee history. Read more at tallahassee.com/tlh200. Ana Goñi-Lessan can be reached at agonilessan@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Tallahassee fire of 1843: How Mayor Francis Eppes responded