Pay even higher rent, Boise? What government deems ‘affordable’ just got a lot costlier

Want affordable housing? It now may cost you more than you think — or than you can actually afford. The government’s definition of “affordable” just allowed some rentals to become a lot more expensive.

The change is affecting the city of Boise, which is already home to numerous government-supported living units and is seeking more. As rents in Boise have skyrocketed and wages have lagged, the city has recalibrated what it means for rent to be considered “affordable.”

In the city’s annual update of its affordable rent guidelines, the median income for Boise households has increased sharply. That means what qualifies as “affordable rent” has increased too.

The median income for a three-person household last year was $67,800. In data updated on the city’s website in mid-June, that increased to $78,796. That’s a 16% increase in one year.

From last fiscal year to this fiscal year, median income was determined to have increased roughly by 15%, depending on household size, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD.

What exactly does that mean for rents? And is the new data really accurate?

Let’s consider the second question first, because it provides context for the first.

HUD sets income limits that determine who qualifies for HUD-assisted housing programs. HUD bases its data on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The data are for the Boise metro area: Ada, Boise, Canyon and Owyhee counties.

Jan Roeser, regional economist for the Idaho Department of Labor’s Southwest Region, said local incomes are rising in response to soaring housing costs. Service industry employers during the pandemic have boosted wages to entice workers. Businesses are still constantly looking to hire. The influx of new people to the Treasure Valley means even more service workers are needed too.

But Roeser said the American Community Survey has received less participation recently, potentially leading to inaccuracies.

The survey is continuous and provides yearly data. The Census Bureau calls it the “premier source for detailed population and housing information about our nation.” While participation is mandatory, people who skip it are rarely prosecuted.

What higher income thresholds mean for rents

The increase in median income means that monthly rent that’s deemed affordable for that three-person Boise household earning the median income of $78,796 just rose to $1,970 from $1,695. That means $1,970 adds up to nearly $24,000 per year in rent — or a difference of $3,300 per year compared with what was previously considered affordable.

If you haven’t received a raise, or you received a modest one, these new numbers mean rent is becoming less affordable.

Median-income and wealthier households are not eligible for rental housing supported by federal programs, including rent vouchers and tax-credit subsidies for developers.

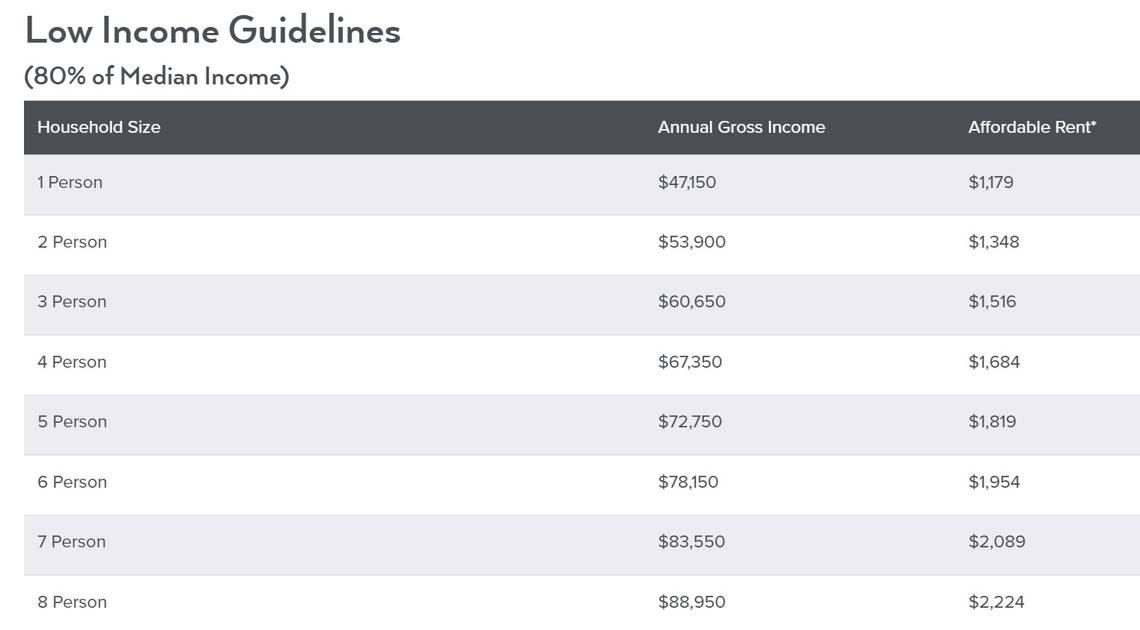

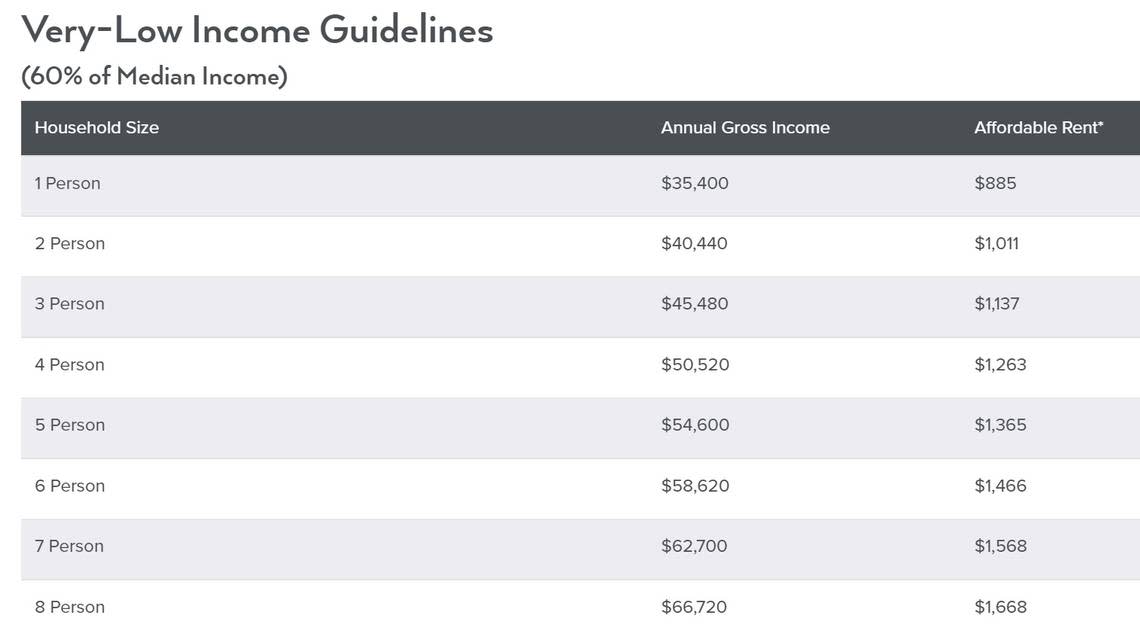

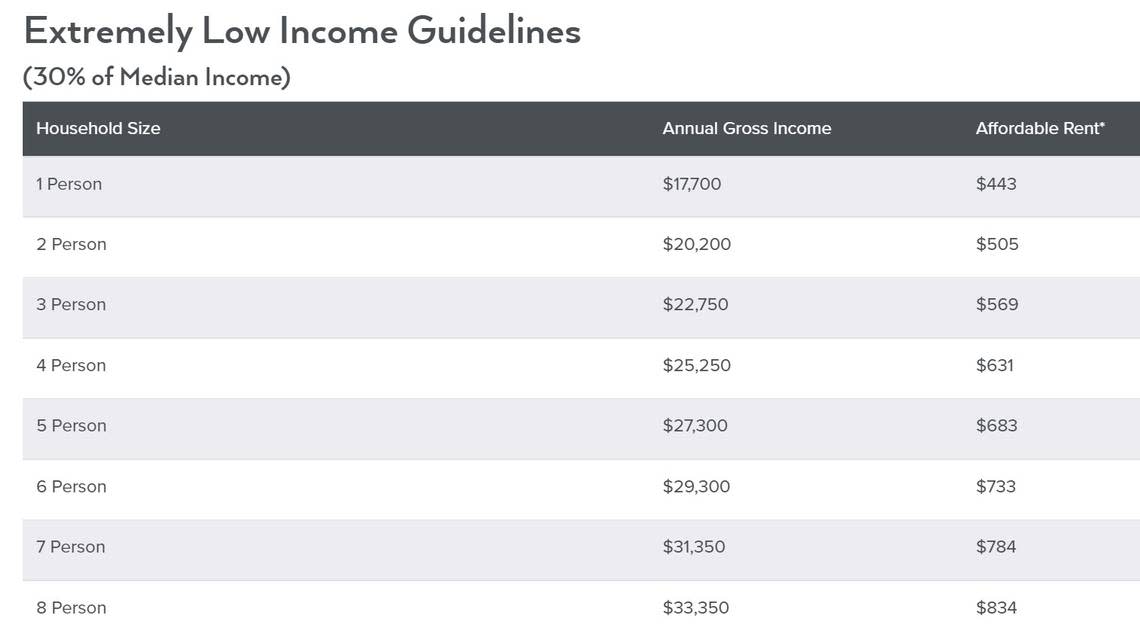

But the new numbers help shape who qualifies for the limited supply of government-assisted affordable housing. Many of the affordable housing options in Boise are targeted at specific demographics: low-income people earning 80% or less of the median income, very low income people earning 60% or less, and extremely low income earning 30% or less.

The U.S. government defines affordable rent as 30% of a household’s income. Anyone paying more than 30% of income on rent is considered cost burdened and may have difficulty paying for other necessities. (The rule of thumb applies to low- and moderate-income households. High-income households can afford more than 30%.)

A three-person household earning 80% of Boise’s median income made $54,250 last year. This year, the median is up to $60,650. Under the government’s 30%-of-income standard, that means that household could pay — and government-subsidized housing could charge as much as — $160 more in monthly rent, up to $1,516 from last year’s maximum $1,356.

And, of course, if that same household from last year didn’t increase its income, it’s now earning below the 80% threshold.

Take a look at these four tables — one each for median-income, low-income, very-low-income and extremely-low-income households:

Government assistance lags behind demand

The rent limit for a one-person, extremely low income household earning 30% of the area median income’s “affordable rent” just went from $396 per month to $443 per month. But a typical studio apartment is now often renting for more than $1,000 per month, said Deanna Watson, executive director of Boise/Ada County Housing Authorities.

Watson said that widening gap is a big concern.

It’s especially a problem for tenants who depend on federal housing vouchers. Known as Section 8 vouchers, they cover the difference between what a household can afford to pay — that 30% — and what a private landlord is charging for rent.

But the money for vouchers is limited, some landlords don’t accept vouchers, and applicants often end up on waiting lists for a year or two or longer.

“Oftentimes people don’t apply for (rental) assistance until they need it, and oftentimes they’re in crisis,” Watson said by phone. “Crisis is usually meant to be a short-term, acute situation, not chronic, but they stay in that, because they can’t get the assistance that they need to get out of that state.

“So the funding picture is inadequate. And the way the programs are designed is inadequate.”

Watson said the Boise/Ada County Housing Authorities mostly serve people earning 50% of the area median income or less. But she’s also seen an increase in people falling below the 80% threshold as rents rise faster than their incomes. She said some renters may receive a 30-day notice that their rent is increasing $400 per month.

“Even at 80% of (area median income), that’s a huge additional cost on a monthly basis,” Watson said. “And people are faced with either sticking with it, because they’re concerned that they might not find a better deal, because everybody’s bumping up the rent, or leave and then not be able to find something.”

Through the federal government’s emergency rental assistance program, Watson said the Boise/Ada County Housing Authorities have distributed $34 million to 7,000 families. Her department is trying to make the money last as long as possible. But eventually, in a year or two, it will run out.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, rents in Idaho’s capital city have boomed and the city has repeatedly been ranked among the least affordable housing markets in the country. The median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Boise is $1,431, according to Apartment List. Since March 2020, median rent in Boise has increased 47.4%.

“What we’ve been doing is holding back an even bigger crisis with this temporary funding,” Watson said. “And when it’s gone, I’m concerned that the social service system is going to be completely overrun, without resources to meet it.”

Will the market finally help?

Roeser, the economist, said the housing market can be volatile while wages are “sticky,” meaning wages typically don’t move up as fast.

But even a 15% median-income increase is not enough to keep up with rising housing costs in the Boise area.

Two market forces might change the trend and lend struggling renters a hand. First, wages could keep rising fast. “With the increase in housing, it makes sense the wages would follow,” Roeser said by phone.

Second, she said it’s “highly likely” that the growth of housing prices will slow or cease. The Boise-area house-sale market already has experienced a sharp drop in buyer interest.

What Boise is doing

Boise has created several initiatives to increase affordable housing by using city-owned land for its housing land trust, offering incentives for developers to build more affordable housing and rewriting its zoning code to allow a diversity of housing types.

“(If) you’re providing housing for people at all income levels, really the housing type diversity is fundamental to achieving that,” City Planning Director Tim Keane said by phone. “If you only start building one or just a few housing types, you’re really making it difficult for lots of different people to live here.”

In February, Boise Mayor Lauren McLean announced a plan to partner with developers to build 1,250 affordable apartment units in the next five years for low-income, working class renters. The city also aims to preserve 1,000 apartments for people earning 80% of the area median income or less. And an additional 250 units would be for supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness. That’s a total of 2,500 housing units.

Keane said housing affordability will determine Boise’s success.

“When it comes to shaping the city such that we are a city for everyone and accommodate people of all income levels, it’s of the utmost importance,” Keane said.

Where to find affordable housing

Here are some Boise affordable housing projects that have opened recently and that you may want to check out, plus some that are planned:

Adare Manor, 2419 W. Fairview Ave., opened 2019, 134 apartments total, 120 for renters earning 60% AMI or less.

Thomas Logan Apartments, 520 W. Grove St., opened 2021, 60 apartments total, 45 for renters earning between 30% and 60% AMI.

State and Arthur Apartments, 3914 W. State St., planned, 40 apartments total, 35 for renters earning 80% AMI or less and five for people who have experienced chronic homelessness

Moda Franklin, 227 S. Orchard St., planned, 205 apartments total for renters earning 60% AMI or less.

Block 68, 1010 W. Jefferson St., planned, 450 apartments total, 25 for renters earning 80% AMI or less and 130 for renters earning no more than 120% AMI.

And take a look at this map of federally supported (mostly subsidized) rental housing across Idaho for families, elderly people, and people with disabilities. Zoom in on your local area and click on a peg for details:

Map: Hayat Norimine. Data: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development