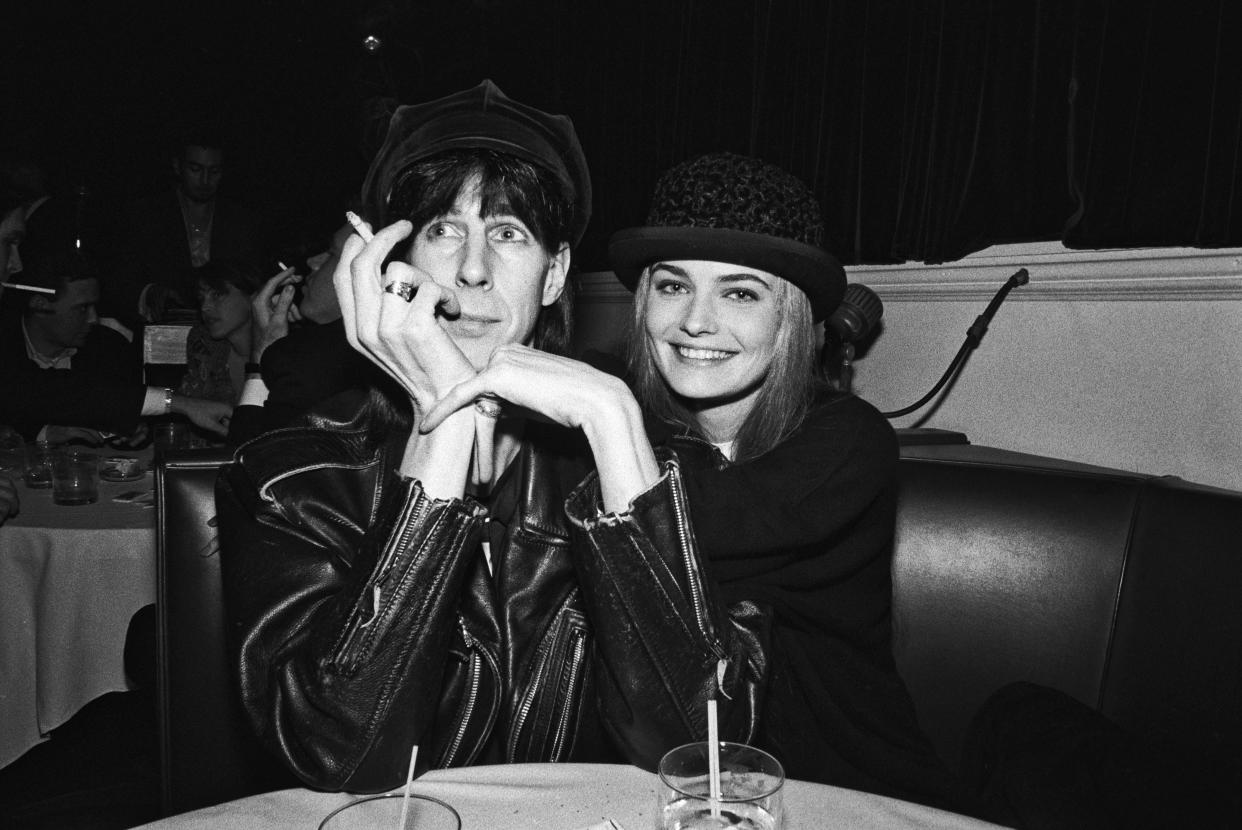

Paulina Porizkova on grieving Ric Ocasek: 'I'm still struggling'

This is the final instalment in Yahoo Life's Unapologetically Paulina video series with Paulina Porizkova.

On the morning of Sept. 15, 2019, I went to bring my husband, Ric Ocasek, his morning coffee; I thought he was sleeping kind of late. I walked in and he looked like he was sleeping — until I set the coffee cup down and I could tell from his face that wasn't sleeping, though he looked very peaceful. And there was a certain amount of foreboding as I walked into the room; there was some sort of knowledge of what I was about to find. It's funny how your mind and your body somehow shield you so that you don't fall apart. But I kind of did fall apart anyway.

I remember thinking, Oh, they never show this part in movies — like one of the insane thoughts that just flitters by you. I saw what happened. I felt his cheek while thinking, Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God. And in my mind, I kind of calmly walked out of the room and went downstairs and told the boys [sons Jonathan and Oliver, both in their 20s] what had happened, but instead I started wailing and my legs gave out and I couldn't walk, so I had to crawl downstairs on all fours. And this is what I found to be really amazing, and in hindsight, you really don't know how you're going to react.

You know when you have these nightmares where you're trying to run away from something, but you can't really move? It was exactly that same feeling. And you're so torn; you're bouncing between what you've just seen, how your world has just come to a complete screeching stop and then how you're reacting to it. All of this is going on in your brain at the same time. It's just so much information, and then it just kind of shuts down on you.

The interesting part of grieving to me is that, unlike heartbreak — which just leaves you completely raw and exposed — grief is almost like a time-release. It's measured out to you in doses that you are able to still function with to a certain extent. You can go numb — or at least I did, for a large part of the aftermath. People would speak to me and I couldn't understand them; it really felt like people were speaking a totally different language. And this is of course when you have to deal with lawyers and deal with money and accountants and figure out what's supposed to happen and then make decisions about this and that — and I remember thinking, "I don't even know what you're saying, so how can you expect me to make any sort of a decision?" That's the rough ride of it: Being so unprepared, then being put into a position of making some extreme life decisions when you're absolutely not able to.

Grief is a little bit like natural childbirth. You go through it and then when you come out on the other side, you go, "holy s**t. I did it. I was able to withstand it and here I am; I was able to take that on." And yes, you can choose to forget it. You can choose to pat yourself on the back for having overcome it.

I think the one thing that it did for me is that it illuminated this whole world of loss that, unless you've experienced it yourself, it's like somebody trying to describe a room to you that you've never seen. It's incomprehensible unless you go through it yourself. And then once you've been through it, you can understand everybody else in that situation, so it really widens your empathy. That's the beautiful thing that comes from suffering is to understand other people's suffering. You what it feels like. It makes you a better person in that way. I don't think it makes you more resilient necessarily, but it makes you realize what your resilience level is. And I'm still struggling. It's a year and a half later, but it's still at times really, really difficult to be alone, to be in a situation that I never anticipated, to completely restart my life over.

But I really do think that the grieving process is individual. I think that if people want privacy when they grieve, then that should be afforded to them, because everybody reacts differently to this. We all feel the same things, but our reactions are different. For me, I'm not going to allow anything to fester in dark corners. I will sweep out the dark corners, which are secrets. I don't want to be a part of that anymore. So for me to be public about my feelings and about how it feels, and then understanding that there's a whole community of women that feel a similar way and that connect to me because of shared trauma or shared pain, it's really rewarding because then you don't feel so alone.

Because you do feel really lonely; you feel really isolated after something like this happens. There's a certain amount of grieving that you're supposed to do, where people say, "Oh, you poor thing, you're grieving. We totally get it." And then at some point people get bored. This is just human nature. It's not like there's anything mean about it or anything like that. It's just that everybody will get sick of you talking about the same thing forever. So when they get sick of you talking about it, then it is just you and your thoughts. And so I've found it really helpful to communicate with people online that were in similar positions where we can say, "I'm not alone, and you're not alone."

Right now I feel like I'm in a much stronger position than I have been in a long time. I feel like I'm getting my voice back and reclaiming who I am. My biggest hope for the future is to continue to figure out who I am on my own. I've been a part of a couple for so long that finding out who I am outside of a couple is really hard and really traumatic. I don't like it, but it's like taking cod liver oil — it's good for me. I don't like how it tastes, but it's good for me.

—Video produced by Stacy Jackman.

Read more from Yahoo Life:

Want lifestyle and wellness news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Life’s newsletter.