In their own words: Ex-skinhead, grandma of 10, a millennial talk race in Kansas City

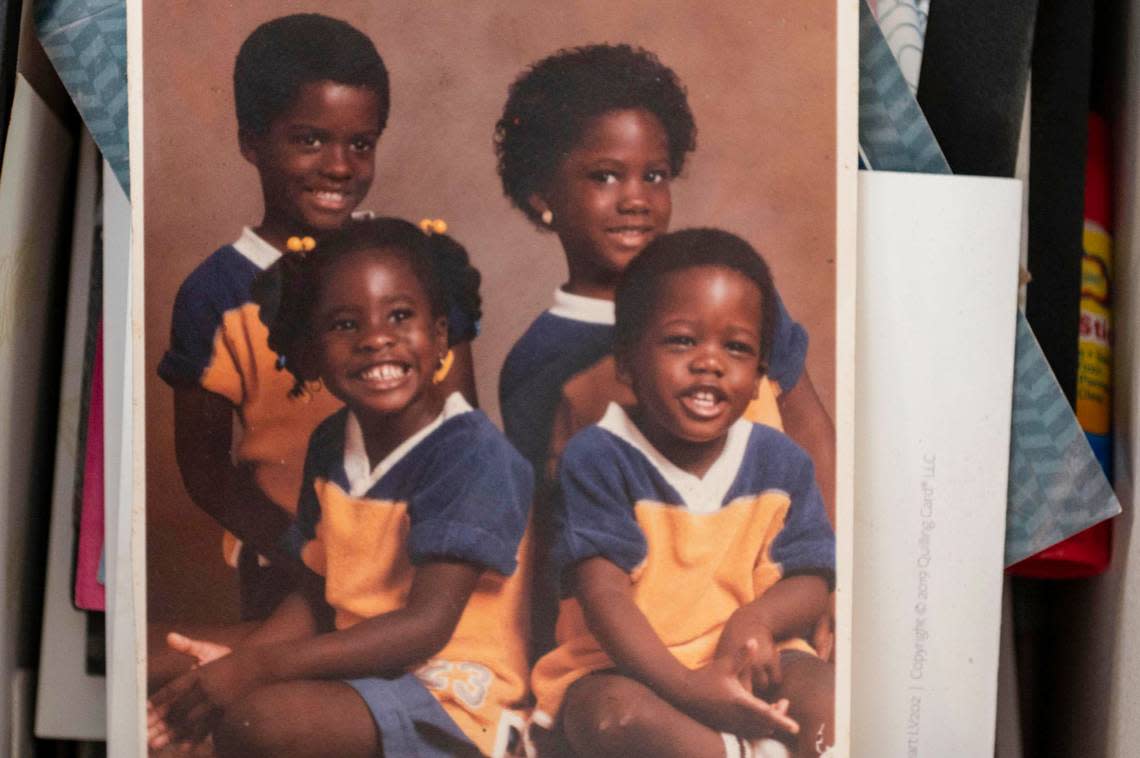

LaKiesha Moore grew up in Compton, California. She is Black.

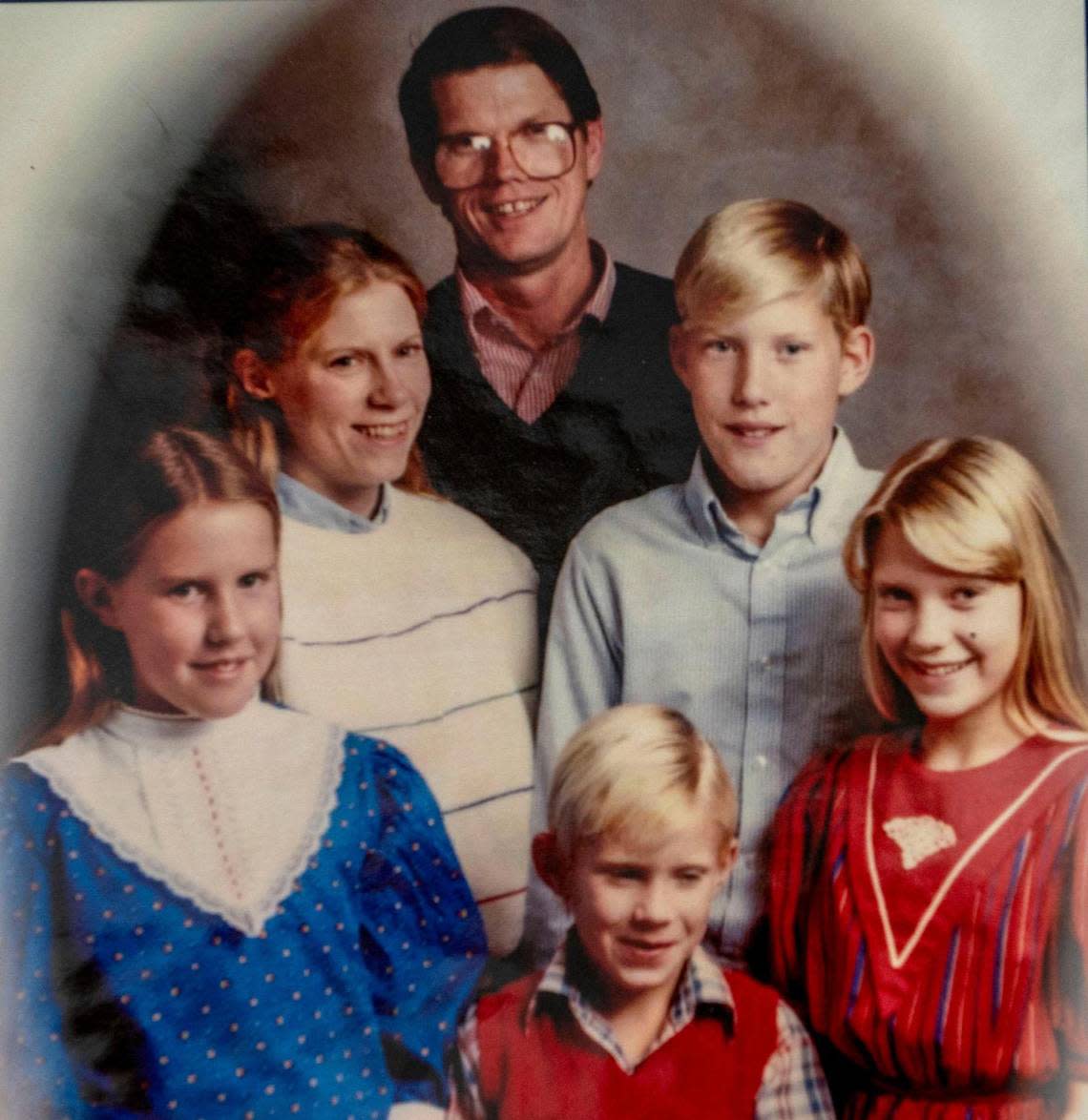

Her husband, Matthew, grew up in Ames, Iowa, and New Mexico. He is white. And he used to be a skinhead.

His conversion involved talking with Black people about their struggles and fears, conversations he says made him realize that throughout his life, doors had opened for him simply because he was white. Yes, race had played a role in his life, for the better.

Kansas City will hear more about that on Saturday at a public forum on race, where the Moores and others will speak and where audience members are invited to talk about “everything people are too afraid to talk about,” the flier says.

No question will be off-limits, no question inappropriate, promises organizer Sheryl Ferguson. The event is sponsored by two local social justice groups — Ferguson’s It’s Time 4 Justice and More2.

Ferguson was inspired by Emmanuel Acho, creator and author of the video series and bestseller, “Uncomfortable Conversations With a Black Man.” In the videos, Acho has one-on-one “uncomfortable conversations” about race and racism with famous folks.

Ferguson has gathered speakers from various communities around Kansas City — Black, Asian, Hispanic.

“It’s mainly people that will be able to share stories about their experiences with having racism in their lives,” she said. “There’s no one that doesn’t have a story behind it.”

Those personal stories will serve as icebreakers for what Ferguson hopes will be a constructive discussion in a “safe space,” where media won’t be allowed to photograph anyone without their permission and questions can be submitted anonymously.

“Race is an easier topic when you’re in a bubble, when you have people who are like-minded, when people either have the same lived experience with you or they share the same sentiment toward race,” said LaKiesha. “Easier that way to have those kinds of conversations because it’s woven in the fabric of your existence, of your conversations.

“It’s when you have to step outside your understanding or your experience or you have to go into someone else’s space and their experience is different that it’s difficult to navigate. (But) once you’re aware of it you can’t be unaware of it.”

We spoke to four of the panelists, including the Moores, Ferguson and Kansas City entrepreneur Eze Redwood.

These are their thoughts on race, edited for length and clarity.

LaKiesha and Matthew Moore

The Moores moved to town during the pandemic in late 2020 and will celebrate their third wedding anniversary in a few days.

LaKiesha, 43, works remotely for a hospital system in New Mexico, where the couple met at a Black community event. Matthew, 46, is an HVAC technician.

We talked with them on a warm, muggy Sunday in their East Side home.

Q: How has race played a role in your lives?

LaKiesha: “I grew up in mostly Black and in Black and brown communities. So I learned about what being Black and proud is, I learned about Black history. I knew about Black hair. I knew everything there was to know about Black culture because I lived it and I was saturated in it.

“It wasn’t until I had to leave that community, and I had to leave what I was saturated with to where I had to say hold on a second, you’re saying bigoted things. Or you’re being insensitive toward people of color. It’s like you kind of know but you don’t really know (about racism) until you step out of your understanding.

“I actually make a special effort to make sure I’m in a safe space. A safe space means I can talk freely about racism when it comes up. I can be a Black person all day every day. I don’t have to explain my hair, I don’t have to code switch. I can speak Black English vernacular, I can speak however I like.

“Code switching is when you change, maybe not your language, but maybe your vernacular, the way you speak, the comfortable way you speak, and then you switch it to what’s considered socially acceptable in white culture.

“So when I’m speaking this way (to The Star), this is how I speak at work, this is how I speak in white spaces, for the most part. But when I’m talking on the phone with my cousin it sounds like, there’s a lot of drawl, it’s a lot of slang because that’s how I grew up.

“But when I am not in a safe space, or when I know I have to put on, I guess a coat of armor, my language changes, my demeanor changes. The way I dress changes.

“And I’m still working on that. I’m still working on how to be authentically Black in non-Black spaces.”

Matthew: “I was raised conservative, Republican, right-wing Christian, things like that. Never stopped to think about them. God Bless America. Everybody has an equal chance here and if somebody’s not doing as well as somebody else it’s because they made bad decisions.

“So I was on my way to making bad decisions. Some years later I’m running around with skinheads and just always bored and getting into it, being ignorant.

“I landed myself in enough trouble that I was getting some good reasons to repent and kind of return to the faith of my father.

“Ended up in Calvary Chapel Church, which did nothing to interrupt my stereotypical, judgmental, right-wing Christian thoughts and beliefs. I was hard-hearted. I didn’t know any better, but then I didn’t look for a reason, I didn’t know anyone’s personal experiences because I stayed in my comfort zone with my comfortable beliefs.”

LaKiesha: “I was 20 and I was in AmeriCorps NCCC, a national organization where you do community service and you live on a campus. And all of a sudden I was surrounded by white people.

“Now I wasn’t afraid of white people. But I put my guard up because all of a sudden I had to start talking about hair. All of a sudden I heard the racist jokes. And these are people I had to work with, closely, for a 10-month span.

“I didn’t have all of the language that we have now. I didn’t know how to say ‘that’s bigoted, that’s racist.’

“I was in a team of 12 people, most of them white, from everywhere, from Wisconsin to Kentucky to New York, California. Us being close and having to work together for 10 months, it rocked all of our worlds.

“All of us were having these deep conversations because we had to work in close proximity doing hard laborious work, traveling together. And the conversations were deep and it hit the heart. People that had never experienced other Black people were a part of my team.

“I truly believe that our ability to live together and have these deep conversations made our thoughts shift.

“And I trust them. I trust them with my life.”

Matthew: “It was some years later that things fell apart at the church I was going to. And I was searching for a much more authentic and real relationship with God that I started to discover the Eastern Orthodox Christian church. While I was there, somebody introduced me to St. Moses the Black (a 4th century criminal who found humility and kindness).

“He’s my hero. Through my relationship and my prayers to him, my eyes were opened.

“I had developed some relationships in my community in Albuquerque with some Black folks and had deep conversations with them about their experiences that were outside my experience before that.

“Hearing about the types of the struggles, the fears, the hindrances that they have in their lives were outside of my experience. Doors had always been open to me if I put myself in the doorway.

“I had caused a lot of problems for a lot of people and never faced the consequences that some of them had for much less.”

Q: Why do you think that was?

Matthew: “Because of my skin color. Because white folks get a pass and Black folks don’t.

“Most businesses are owned by people who look like me. And we are a lot more likely to give a second chance, or a first chance, to somebody who looks like our children.

“So I’ve never had trouble getting a job. Even if I wasn’t qualified for one. I’d still talk my way into the door. I got into the trades, first plumbing, then electrical, then HVAC.

“I know Black men who have gone to school and got better grades than I have who never could get a job because they’re stereotyped from the moment the interview starts.

“And it’s not because there’s not applicants or people with the licenses in the Black communities because white men don’t trust them, don’t hire them, and don’t think about their own beliefs in the hiring process.

“It’s so bad that a lot of our brothers out here just don’t even bother trying to get into the trades anymore because slammed doors, one shut door after another breaks you down.”

Q: How do you define racism?

Matthew: “By belief in the superiority of a culture or a race over the other ones and the denial of the setbacks and barriers against another race.

“Growing up, all I knew, I knew that Black folks had higher crime rates. Didn’t know anything else about Black folks. Just that they had higher crime rates. And nobody ever bothered to tell me, well, business owners won’t hire them. Nobody bothered telling me that they get sentenced 60% or more over what people who look like me in prison.

“Nobody had ever told me about how those kinds of barriers interrupt family lives, which interrupts education, which interrupts the amount of money you bring in, which interrupts your ability to function in society on the same level as some do.”

Q: How do you define racism, LaKiesha?

LaKiesha: “The mindset that there is a superior race or is a superior culture, that holds all the power and will not share that power with other people. Whether it’s job opportunities, money, being able to live where you want to live.

“We all uphold racism in some way. Whether it’s power, whether it’s me code-switching. Whether it’s me believing that we have to have a certain look or certain way or function in a certain way in order to be successful. That’s all a made-up construct.

“Somebody out there decided that you have to be this in order to be successful in this country. Or in order to be a whole person you have to act like this, talk like this, walk like this, make money like this, wear your hair like this, whatever it is. That proximity to whiteness is not just skin color. It’s cultural, it’s in the soil of this country.”

Matthew: “Because in it is also the expectation that everybody should be at the same level. Everybody should have shed the same pain, even to catch up with people who have not ever had to bear that pain.

“In the end, a government can’t heal our societal ills. It takes us person-by person, venting, and loving our neighbor.”

Q: How has race affected your relationship, marriage?

LaKiesha: “So I’ve been Black all of my life, and Matthew is new to what racism is. It’s about coming out of your comfort zone and creating another one.

“I had to vet this man differently than I had to vet anybody before. I had to ask certain questions, I had to listen more intently. I had to figure out who his family was and I had to make decisions about being with him that I never had to make before. What are your core values? Is this fetishism? Because Black women are not a part of the, on the higher end of the beauty standard, right?”

Matthew: “Wrong.”

LaKiesha: “And I’m real Black. I don’t mean in color, I mean in culture.

“So, you know, having to make the decision to accept love in this package. (She pointed to Matthew.)

“So I just didn’t allow it to get in the way of having a really solid relationship with a man that had all the things, checked all the boxes. Loved God. Loved his family. Just good, solid, core values that I wanted in a partner. Didn’t think I would find it. And here he comes, bopping along in another package.

“It was tough. But I had to get past it. And here we are.”

Q: Did he tell you he used to be a skinhead?

LaKiesha: “In our first couple weeks of dating. Yes. He told me.

“I’ve dated some horrible humans before, too. Gangsters. Drug dealers. You know what I mean? And I believe that people can change. “Because your past is your past, a history is a history. Is his more complex? Absolutely.

“That means you have a very interesting story and you deserve to tell it and to remind people that people can change.”

Q: Some people say stop talking about it because it makes things worse, or that racism doesn’t exist.

Matthew: “People who say it’s not an issue are the people who are on top of the food chain. The people who are comfortable, the people who have the system set up in their favor. Of course it’s not important for them to talk about because it’s not affecting them or their family.

“It does affect my family. And I’ve made the decision that it’s going to affect me. I made the decision it was going to affect me before I had married into my family.”

LaKiesha: “You can’t stand for us if you don’t believe us, or you’re doubting us. You have to believe that racism exists, first.

“It might not catch up to you but it will catch up to your children. It will catch up to you at work when nobody wants to talk to you, or somebody calls you a Karen. Or somebody calls you racist. It’s going to catch up to you because you refused to have the conversation.

“So, you can ignore it if you want. But you’re not a part of the solution and you’re a part of the problem because you won’t help tell the story, you won’t listen to the story.

“I almost gave up. And I still have a hard time, holding hope for this country, for this society. It’s hard to hold hope for people who just want to say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t exist. Oh, there was President Obama.’

“It’s hard to hold hope for people who won’t even acknowledge (it). If I had cancer, it’s like my doctor saying, ‘Yeah, but, you know, it’s not a big deal. You’ll be fine.’”

Eze Redwood

People who live in Jackson County might want to commit this name to memory: Eze Redwood. (Say it: “Ezzy.”)

After talking to community leaders and hearing their stories, the 36-year-old entrepreneur, who is Black, is newly hyped up about county politics, “mainly because it’s a (bleep) show. I didn’t realize how much of a (bleep) show it was until I did, which was a couple of weeks ago. But now I care a lot.”

Redwood is a vice president at Lillian James Creative in Kansas City, a marketing firm that acquired the strategy consulting company he founded, he said. He also runs an entrepreneur and small business council in Kansas City.

He graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts with a double major in political science and philosophy of religion, with concentrations in East Asian studies and international relations.

He’s so on fire now about how politicians are running the county that people think he’s running for office.

He’s not.

But his business council is hosting a forum this month for small businesses in minority communities in Jackson County.

We spoke to Redwood at the Lillian James offices inside a former city utilities building built in 1866, making it one of the city’s oldest buildings near the 18th and Vine Jazz District. The renovated limestone building, open and airy inside, is home to several minority-owned businesses.

Q: When did you realize that race would play a role in your life?

Redwood: “I think that for me it was less that race was going to be really important and more that race tended to correlate to differences, which I couldn’t quite put my finger on at that time. I was in middle school, in south central LA, which at the time was kind of a wild school, I think it’s a lot better now. I was fortunate to test out of a couple of grades and kind of move directly to high school.

“But for that short period, before I tested out, I’m in gifted classes and we don’t have all the pages in our books. Our textbooks are raggedy, missing pages, they’re worn down, they’re several versions back.

“And then just seeing the difference going from that experience to where I’m at Santa Monica High School, in LA, close to the pier and the ocean and the beach and there’s a lot of affluent people who are also going to school there.

“It was a lot different. And for me, that was the first time I really realized that there are factors outside of just who we were that were determining our success. And I think I was maybe 12 at the time.”

Q: What changed your perspective on how people of color are treated?

Redwood: “I grew up partially in Little Rock, Arkansas, and Arkansas is very Southern and it’s very overt racism, which is what I grew up around.”

Q: What did overt racism look like?

Redwood: “When you’re in the South if you haven’t been called the N-word, then I question where in the South you were. Were you in the Midwest South or actual South?

“I’ve been to diners where I’m the first in and last to get served. And there’s a lot of people coming in, like 15 or 20.

“I’ve been to cities and towns where in some of those places you walk into a diner and you get looks that make you understand that you’re not welcome there.

“You get flipped off. You get people throwing up the white power signs right at you while you’re driving. That’s what I mean by overt.

“When I came to Kansas City, I expected it to be different. It seemed more eclectic. It seemed more open-minded. But what I realized is that, one, inside the city there are still systems in place that are racist, even if the people aren’t racist.

“Then the other side of it, I had someone I was talking to and her family lived in Lathrop, Missouri. And I went out there and just kind of an ‘oh heck’ moment was when I’m talking to her childhood best friend’s daughter, who was I think 8 or 9, and she asked me why my hands were so dirty.

“And it made me realize that not only was there a lack of exposure, there was just a lack of conversations.

“And what that ends up translating to as I met more people in the town is that the portrayals in the media would be the only thing that they had to go off of and that defined and embodied the entire characteristics of people they weren’t familiar with.”

Q: How do you define racism?

Redwood: “I believe in racism, I don’t believe in race as a word. To me, race doesn’t exist because it implies there are different races. And to me I don’t see different races.

“I see different people who are closer and further away from the equator and thus their skin had to have more or less pigment in order for them to survive.

“I think that race is an artificial construct that allows people to justify their actions and divert away from making their constituents’ lives better and instead insert something they can be mad about because hate is a stronger emotion than hope.

“So when we have these divisions that have been constructed for us, the best way to eliminate those divisions, the best way to eliminate and eradicate racism is to create familiarity. So familiarity with the other culture, familiarity with the other quote unquote races, and understanding that maybe the stereotypes that you were fed and which you have are incorrect.

“And the only way you do that is through exposure and through conversations, and the best way to do that is by creating a comfortable environment to have very real, very open and honest conversations where people can let their guards down and just be who they are and talk freely.

“I think people are so afraid of either getting canceled, they’re so afraid of offending people, they’re so afraid of having their belief system disrupted that they don’t necessarily want to have those conversations.”

Sheryl Ferguson

On Dec. 3, 2019, Kansas City police shot and killed 26-year-old Cameron Lamb, who was Black, in his own backyard. Ferguson knew Lamb and his family — her daughter had dated him in high school — and Ferguson has been a vocal critic of KCPD since then.

Detective Eric DeValkenaere was found guilty of manslaughter, the first white Kansas City police officer in 80 years to face a criminal trial in the shooting death of a Black man.

After Lamb’s death Ferguson became a regular at Board of Police Commissioners meetings and began publicly decrying police shootings of Black people and advocating for a police department run locally, not by the state.

KCPD gave her a certificate of appreciation in 2016 for her work in the community. But she gave it back after Lamb’s death.

She has recently pulled back from some of her activism work. In her spare time she crochets and babysits for some of her 10 grandchildren.

We spoke with her at a Johnson County Starbucks, where she noticed the bulletin board by the front door and made a mental note to return and post a flier for the race forum.

Q: Was there anything in your past that lit a fire in you?

Ferguson: “My mother who died when I was 10, I just always remember that she was part of the NAACP in Rochester, Minnesota, which is really funny because there were only five Black families in town. So she was the president. But who else was going to do it? I never really got a chance to know what she did. I was too young to understand.

“This (race forum) event actually started off with me wanting to have it for school-age children. I wanted to have it for upper middle school to high school, because of the walk that I’ve had in my life.

“I wanted to get this message out because we have too many people that are allowing our children to watch TV and see the (Black) stereotypes and believe that’s who we are as a people. All of us are not like that.

“Everyone is not a monolith. It’s not like, oh, Black people, they always do this. But that’s what society thinks. That’s why white people make sure their doors are locked and clutch their purse.

“That’s why they are letting their dog free in the park without a chain and a Black man asks you to chain your dog and now all of a sudden you’re crying and a victim.”

Q: So now you’ve become a voice in Kansas City?

Ferguson: “We fight for any cause for two weeks. And usually the cause we fight for two weeks wasn’t about somebody here. It’s about somebody somewhere else. And then after that two weeks we go home and we go back to playing PlayStation and we go back to our Xboxes and we go back to our Twitter feeds. And you’ve got people begging for attendance.

“It’s not even the aspect of wanting money. It’s that we need bodies.

“We need people to not only help spread the word, we need for you to write, we need people that have the knowledge of knowing how we can help appeal to the House and the Senate to change the laws that say we have to have the state run our police department.

“Had Eric DeValkenaere been one who had gotten out and known the community, he would have known that Cameron …

“The first interaction I had with Cameron’s giving heart was when my daughter and he were dating, still in high school, and I had a tree that fell in the backyard.

“I went and bought a chainsaw because I’m cheap. I don’t like paying for labor. I’ll figure out how to do it on my own if I can’t get someone to do it for me. So I was actually looking forward to it. I was like, it’s going to be fun.

“And everyone said, ‘Sheryl if you don’t know how to operate a chainsaw. You’re gonna cut off a limb.’

“When I came home my daughter calls and says, ‘Mom, have you been in the backyard yet? You gotta go in the backyard.’

“During the day Cameron and his grandfather came and cut the whole tree up and had it stacked for firewood.”

Q: How often do you think about Cameron?

Ferguson: “He’s part of my life every day. I have to.

“I get tired doing this. But I can’t not think about Cameron because I have 10 grandchildren. And if I don’t do everything I can to change this world, what will they be in? I have five grandchildren who are of mixed race. So half my family is mixed.

“And it’s funny because people probably a lot of times say I’m racist. Honey, I’m fighting for everybody. When Black people win, everybody wins.”

Saturday’s event

A public forum on race is scheduled for 4 to 6:30 p.m July 23 at Community Christian Church, 4601 Main St. Registration is requested at eventbrite.com.