Ostrich eggshells, carved ivory reveal ‘fabulous’ life at 2,800-year-old palace in Iraq

Precious objects made of ostrich eggshells, elaborately painted walls, furniture inlaid with carved hippopotamus and elephant ivory: Welcome to palace life in ancient Assyria.

More aptly, welcome to the snippets of royal life that archaeologists have unearthed from the palace of King Adad-Nirari III in Nimrud, an old capital of the Assyrian empire and city in modern-day Iraq.

Archaeologist Michael Danti, who works at the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, and his team from the Iraq Heritage Stabilization Program and Penn Museum began excavating Nimrud in October. Their work has “progressed really rapidly,” Danti told McClatchy News on Tuesday, Dec. 13.

King Adad-Nirari III took the throne as a young boy, ruling the Assyrian empire around 800 B.C. during a time of fragmentation, Danti said. However, his mother, Queen Shammuramat, “essentially ran the empire. … She went on military campaigns, and, unlike other royal ladies, had royal inscriptions in public places,” Danti said. The queen, also known as Sammuramat or Shamiram, was “a very powerful female ruler.”

King Adad-Nirari III’s palace — or, as some scholars argue, his mother’s palace — is one of the “most poorly known” palaces, Danti said. A British archaeologist excavated a small portion of the site in the 19th century, but many questions remain unanswered.

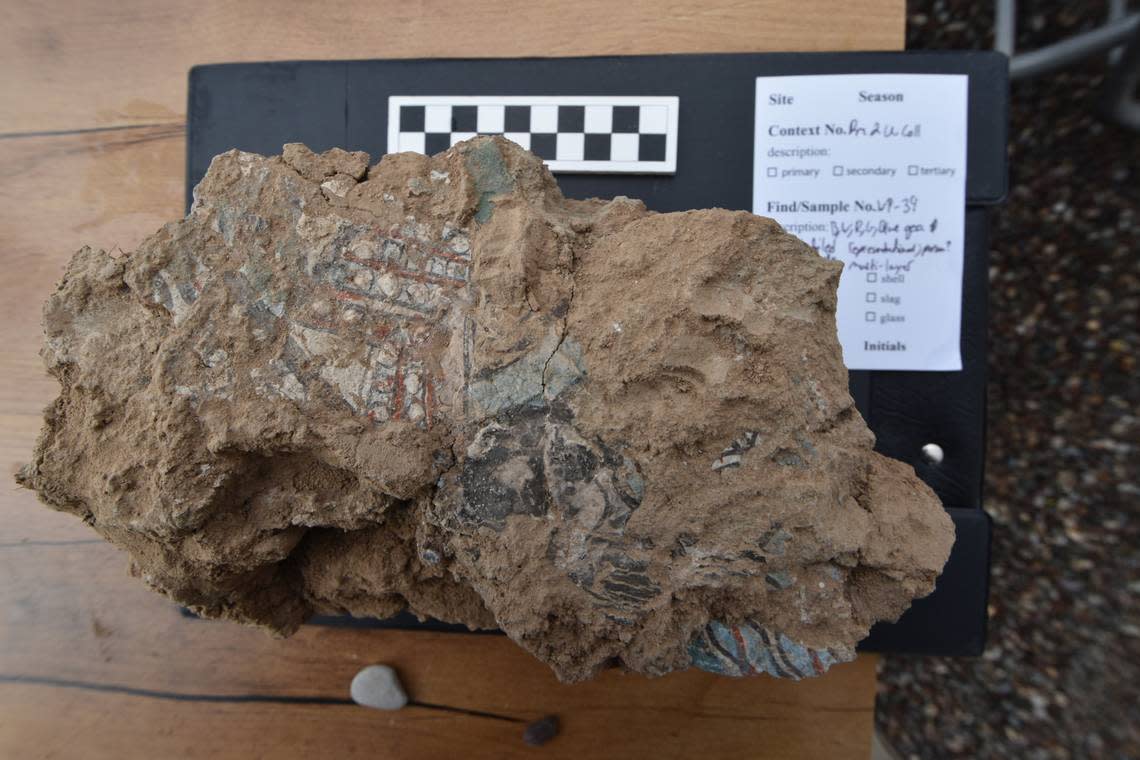

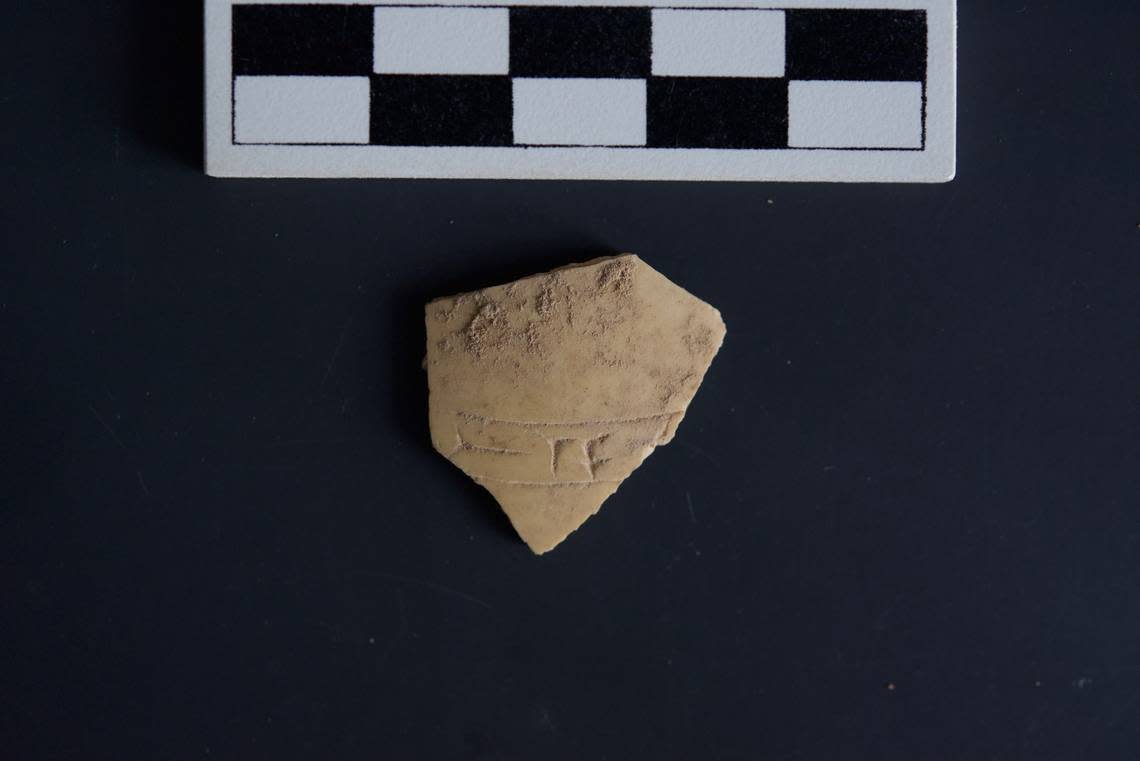

Excavating the 2,800-year-old palace has revealed “amazing” and “fabulous” finds, Danti said. Archaeologists have unearthed fragments of fallen wall paintings with “elaborate” designs, objects made of ostrich eggshells, carved elephant and hippo ivory, bronze objects, inscribed metal slabs and brick pavements, an “unprecedented” marble column base with a style like “no one has ever seen,” and a large slab of marble with a bowl-like indentation in the center and tram-like rails that servants would have used to roll around a metal wagon with a fire inside, he said.

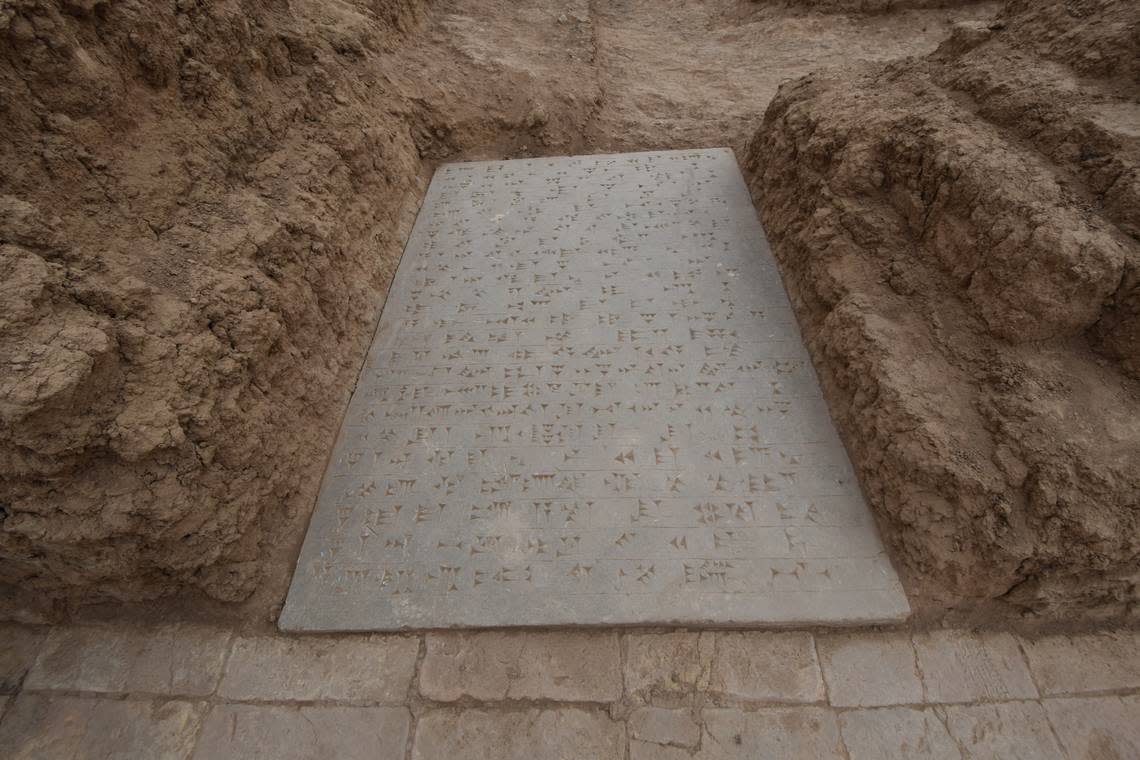

For Danti, however, one find stands out: a door sill with a cuneiform inscription. Archaeologists uncovered and documented the threshold in the 19th century, but the find was reburied amid years of warfare, conflict and fighting in Iraq.

“To see it in person … to see the size of it, the beauty of the cuneiform writing system on it, just the monumentality of it, it blew us all away,” Danti said. “We were elated and we were just dumbstruck. … I don’t know how to describe it, it was the size of the thing and the craftsmanship.”

A few minutes walk away from the palace, Danti’s team is also excavating the acropolis, or “high mound at the center” of Nimrud. The joint team of Iraqi and American archaeologists are clearing away debris left from ISIS explosions, he said. Before the explosion, Iraqi archaeologists had “painstakingly reconstructed” a portion of the Ishtar Temple, a massive temple built around 900 B.C. and dedicated to the Mesopotamian goddess of love and warfare, Danti said.

Archaeologists hope to reconstruct the temple once again — a project that began by de-mining the site and clearing any unexploded ordnance, Danti explained. Once the rubble is gone, archaeologists can assess what’s left of the site and what needs to be done next.

Danti hopes that both excavations will help to bring “a renaissance for Iraqi archeology, to get the cultural sector at large back up on its feet and to sort of revive the art and history from their educational institutions.”

Nimrud is about 20 miles southeast of Mosul and about 240 miles northwest of Baghdad.

Ancient city with ‘massive’ palace emerges from lake in drought-stricken Iraq

Stone carvings — 2,700 years old — unveiled at archaeological site in Iraq, experts say

5,000-year-old silver ring found in Oman gives peek into ancient culture, experts say