Who is Opal Lee, Grandmother of Juneteenth, nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

Opal Lee, known affectionately as Miss Opal and the “Grandmother of Juneteenth,” was instrumental in getting congressional legislation passed to make Juneteenth the 11th federal holiday in 2021.

Lee, who turns 96 on Friday, Oct. 7, is a Texan who has spent most of her life in Fort Worth, where she has been a community activist for decades.

She is nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. The award will be announced Friday, on her birthday, and has a $1 million prize.

Where was Opal Lee born and raised?

Miss Opal was born to Mattie Broadous Flake and Otis Flake on Oct. 7, 1926. She was raised in Marshall, Texas, about 185 miles east of Fort Worth.

Lee and her mother and brothers moved to Fort Worth in 1937, when she was about 10. Lee’s mother worked as a cook, and the family was taken in by friends.

Lee enrolled in classes at a school for six weeks until her mother and father reunited and moved to the south side of Fort Worth, an area of town she’s now lived in almost all of her life.

Opal Lee’s family attacked on Juneteenth, 1939

When Lee was 12, on June 19, 1939, hundreds of white rioters burned everything in their home, which was in a white neighborhood. The police showed up to their home but couldn’t control the mob.

“My dad came from work and he had a gun. Police told him, ‘If you bust a cap, we will let this mob have you.’ Our parents sent us to friends several blocks away, and they left on the cusp of darkness. Those people went ahead and pulled our furniture and burned it. They did despicable things.”

Lee witnessed similar acts in the neighborhood. A Black family owned a home a few doors away but had never moved into it, and instead rented it to white families. Sometimes white people would come and shoot a gun, which would force Black people who were gathering to scatter.

Lee’s family later ended up moving a few more blocks deeper into the south side. Lee said that other than the attack on her childhood home, and a few other incidents, she didn’t have many interactions with violent discrimination during her childhood.

“When I was going to school, going to church, doing the things in my neighborhood that I’ve been doing, I never had any more trouble,” Lee said. “I knew — I rode the buses, or we had street cars in my day and time — I knew where to go and sit, in the back of the bus or streetcar.”

Opal Lee’s family, education and jobs

Lee attended Tarrant County’s only Black high school at the time — I.M. Terrell High School — and graduated at 16.

Lee fell in love and married Joe Roland. They had four children: Jo Ann, Joe Thomas Roland Jr., Thomas Edwin and Gerrald Leslie. But the marriage didn’t last, and she decided to go to Wiley College in Marshall, Texas.

She worked to support her education as a cook, hotel attendant and at the college bookstore. Lee studied to become an elementary school teacher but also worked as a maid at Convair, an aerospace manufacturer that was later partly bought by Lockheed, to support her children.

Lee later earned a master’s degree in counseling from North Texas State University and an honorary doctorate from Texas Christian University.

As a teacher in Fort Worth, Lee met her second husband, Dale T. Lee, who was an elementary school principal. The couple was married for more than 30 years before he died.

Opal Lee’s teacher career in Fort Worth

Lee worked at several Fort Worth school campuses, including McCoy Elementary, and remained at the Fort Worth school district for nearly two decades. She retired in 1977.

Early in her career, Fort Worth was deeply segregated. Public pools were for Black or white swimmers only. Forest Park pool opened for Black residents only on Juneteenth. The next day, staff drained and refilled the pool.

That began to change as Fort Worth underwent integration. Lee’s children participated in rallies and protests, but she did not.

During integration, Lee’s classrooms changed from being all Black to having white and Mexican children. “And you taught the same way you’ve been teaching,” Lee said.

She became a visiting teacher, a role more similar to social work.

Opal Lee’s food bank, farm and activism

Around the late 1980s, Lee was chair of the board of directors for the Metroplex Food Bank near Riverside and Berry, an area of Fort Worth that had a lot of need. Through Lee’s determination, the food bank cleared its debt and began to expand into what’s now the Community Food Bank.

The food bank led to the beginning of Opal’s Farm, east of downtown near the Trinity River. She asked the Tarrant Regional Water District for land and hired workers who had been incarcerated and couldn’t find jobs. The farm grows watermelon, herbs, tomatoes, potatoes, beans and greens for the Community Food Bank, Funky Town Fridge and the WIC Program.

Opal Lee’s march to Washington for Juneteenth

One of Lee’s lifelong missions was to see Juneteenth recognized as a federal holiday.

Growing up in Marshall, Texas, her family would go to the fairgrounds to celebrate the holiday, but people in Fort Worth didn’t seem to.

Juneteenth commemorates the 2.5 years enslaved Texans waited for their freedom until Union troops arrived on June 19, 1865, to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Abraham Lincoln in January 1863 amid the Civil War. Texas was the last state to see these troops.

Lee met Lenora Rolla, who gathered materials illustrating how Black people had contributed to the growth of Fort Worth. Rolla’s efforts later founded the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society, and Lee became a member.

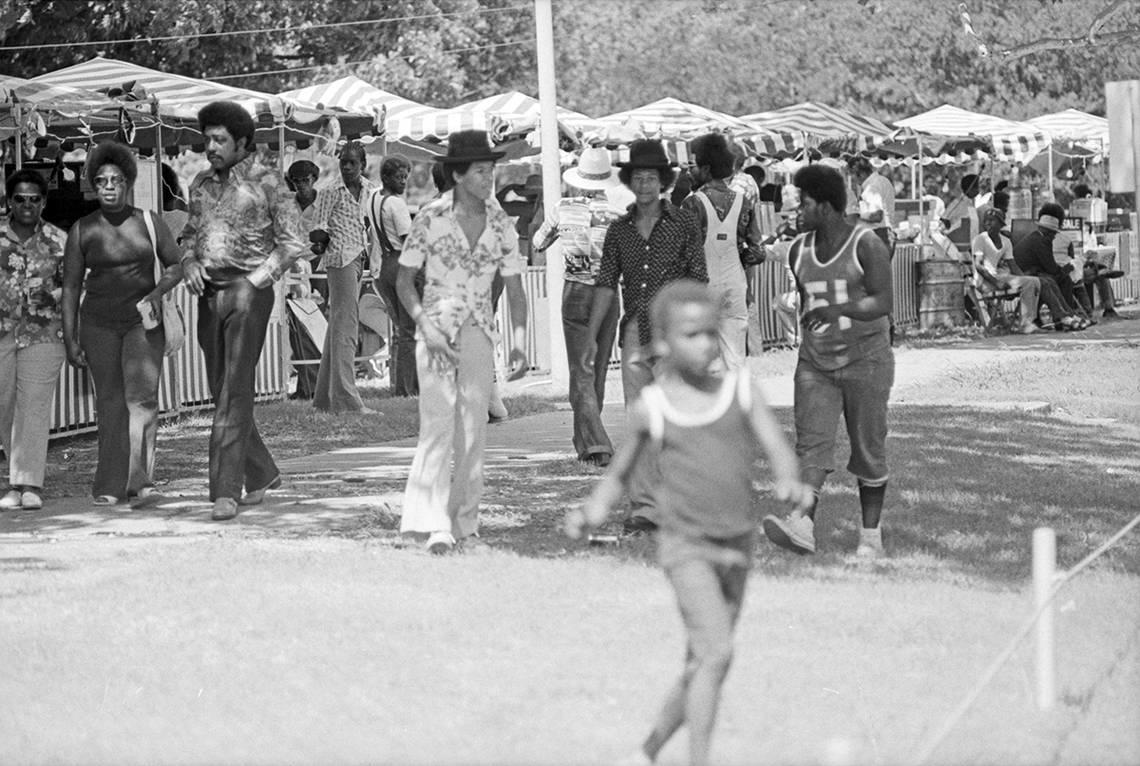

The historical society helped organize Fort Worth’s revival Juneteenth in 1975. More than 30,000 people attended at Sycamore Park.

At 89 years old, Lee made a 1,400-mile walk to Washington. “I gathered some people at my church, my pastor, the musicians, the county commissioners, school board members and they gave me the send off,” she said. “I started walking from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C. … I just knew somebody would notice a little old lady in tennis shoes, and they did.”

She and her team traveled to where she was invited and where there were Juneteenth services, including Denver, Colorado Springs, St. Louis, Chicago, Atlanta and the Carolinas.

She left Fort Worth in September 2016 and got to Washington in January 2017 with a petition. She relaunched the campaign in 2019, crossing seven states before COVID. In June 2021, President Joe Biden signed a federal bill that nationally recognized the holiday. Lee was in attendance.

“I had been to the White House before … but the Oval Office? And to see that many representatives, and senators, and the president, and the vice president, I mean, it was awe-inspiring.”

What did Biden whisper in Opal Lee’s ear?

In her time in the Oval Office, Biden whispered something in Lee’s ear.

“Everybody wants to know what he said, and I say, ‘I’m keeping something to myself. I’m not telling y’all,’” Lee said, adding that he wrote her a check for $6.19, to symbolize the date of the Juneteenth holiday, as one of the first contributions toward the new Juneteenth museum that’s expected to be completed in Fort Worth by 2025.

This article includes information from the Star-Telegram’s archives.