One judicial race may be a KY Supreme Court stress test on partisanship and abortion

Earlier this year, Rep. Joe Fischer, R-Ft. Thomas, had some questions.

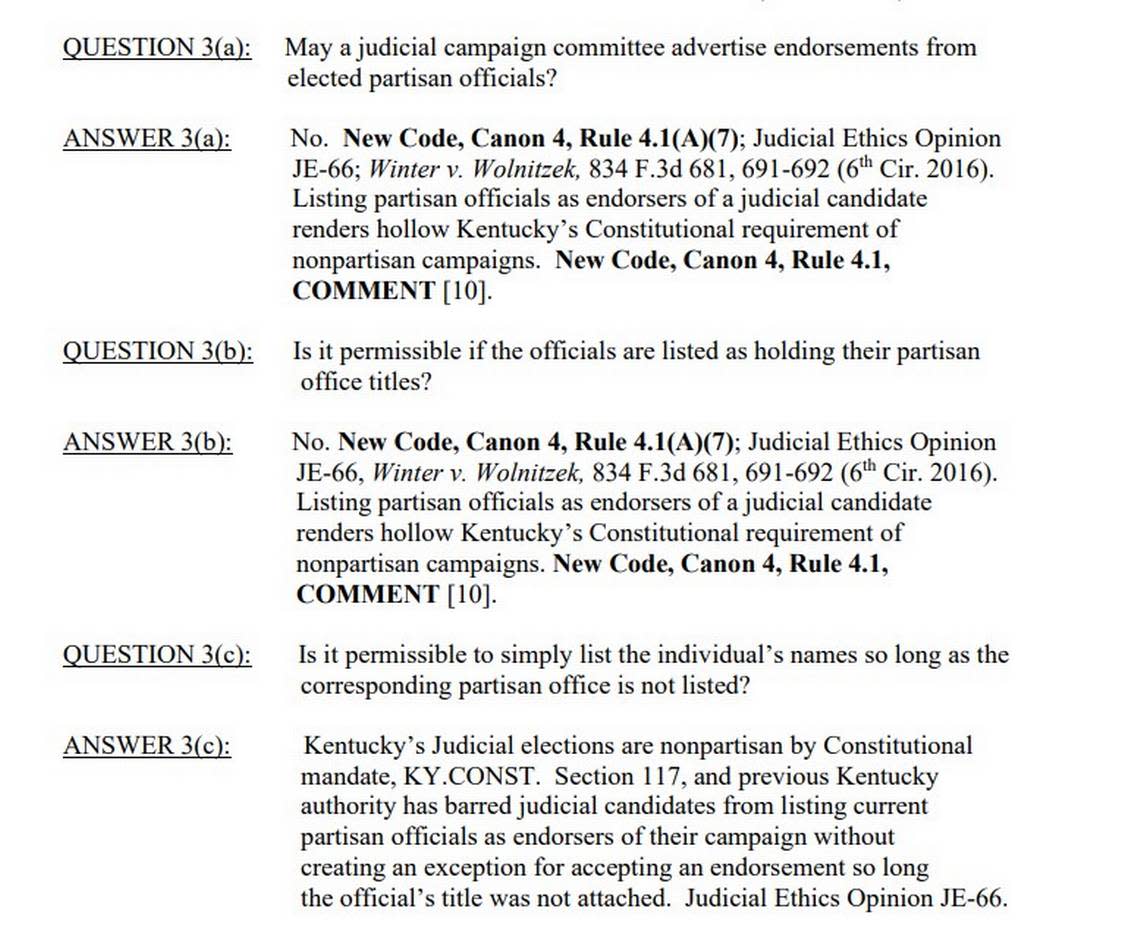

Running for Kentucky’s nonpartisan Supreme Court, Fischer posed to the state’s Judicial Ethics Committee several questions about just how partisan a candidate could make their race.

Can a campaign advertise endorsements from elected partisan officials? Can they use symbols like an elephant or donkey, closely associated with a political party, in advertising? Can candidates announce their political affiliation in mass advertisements?

The questions are as revealing as the answers – which either tell him “no” or provide roundabout permission but warn against “rendering hollow” the state constitution’s requirement that judicial races be nonpartisan. Fischer wants to signal to voters his partisan identity as much as he can.

Fischer is one of the most prominent anti-abortion political figures in the state. He is a longtime Northern Kentucky legislator who authored Kentucky’s trigger abortion ban, which is currently blocked via a ruling in Jefferson County that has been appealed, and its anti-abortion proposed constitutional amendment. The former is likely to come before the Kentucky Supreme Court soon and the latter will be on the ballot statewide the same time that Fischer is in his district.

“Elections may be either partisan or nonpartisan, but all elections are political in nature,” Fischer said. “I personally think that if you’re going to have an election, if you’re going to elect your judges, it should be partisan.”

And his campaign reflects that.

Fischer’s logo touts him as the “conservative Republican” running for Northern Kentucky’s Sixth Supreme Court district, a Congressional District GOP chair helps run his campaign, Republican politicians in the area are beating the bushes with stump speeches about the importance of electing him to the state’s high court, and he’s hosting fundraisers touting the support of prominent Republican state legislators.

His opponent, Justice Michelle Keller, says this campaign strategy constitutes “cheating” the state constitution’s requirement that judges be elected “on a nonpartisan basis.”

“If you have to cheat to win, people will say ‘oh, that’s politics,’ but is that the kind of judge you want? A cheating judge?... He calls himself a constitutional scholar and says how he’s going to protect the constitution. The constitution says judicial elections should be nonpartisan,” Keller said.

Keller has served on the Kentucky Supreme Court since being appointed in 2013 by former Democratic governor Steve Beshear and winning election to an eight-year term in 2014. A registered Independent, Keller would be the most senior member of the seven-person court by nearly five years – and a potential candidate to replace outgoing Chief Justice John Minton as the judicial branch’s highest official, according to Northern Kentucky University political science professor Ryan Salzman.

Ethics in two different campaigns

Despite Keller’s claims, Fischer maintains that his campaign is being conducted by the book.

There are a few points of contention regarding the judicial ethics opinion, initially issues in early April, and how closely it was followed. For one, the commission recognizes a general standard that candidates should not “render hollow” the nonpartisan nature of the races.

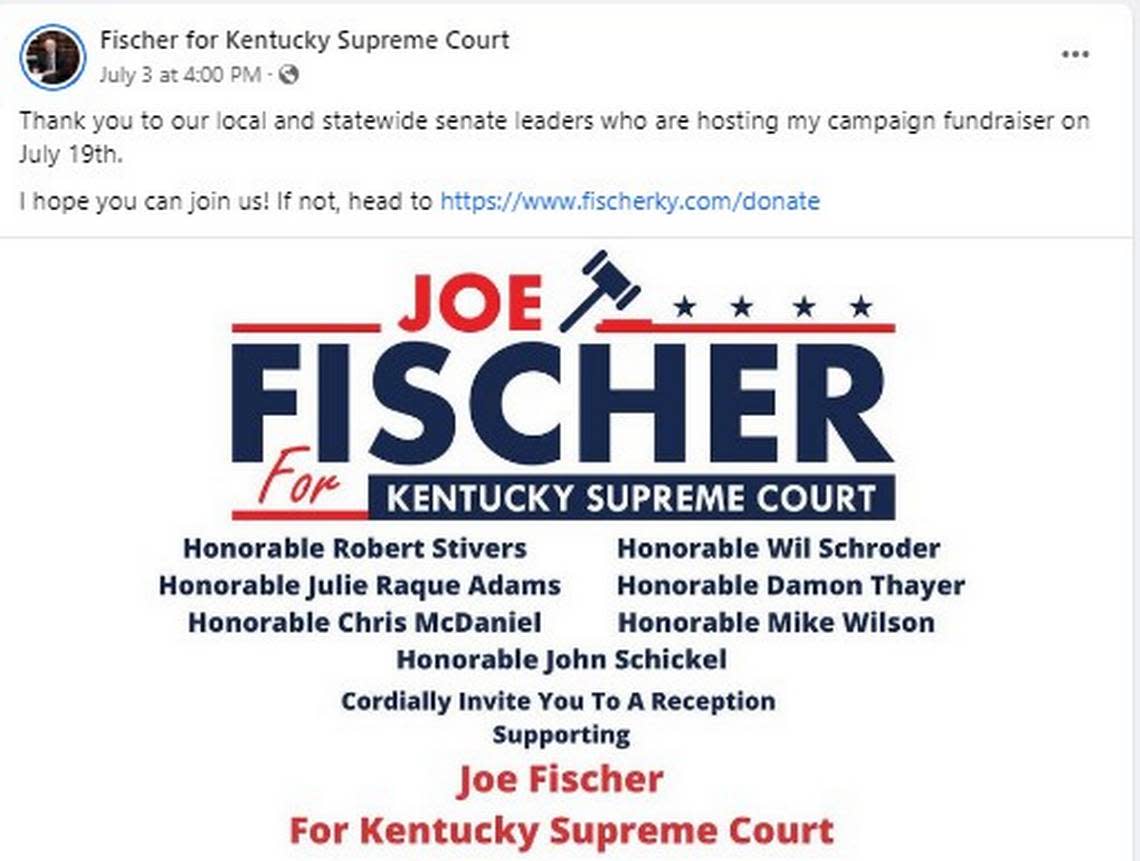

Another complaint has to do with a fundraiser invitation, which took place Tuesday night, posted to Facebook that listed the names of seven Republican Senators as hosts. The list included nearly all members of GOP majority leadership in that chamber, including Senate President Robert Stivers who also co-hosted an event for conservative attorney Joseph Bilby in his bid to unseat Franklin Circuit Chief Judge Phillip Shepherd.

Fischer claims that this did not violate judicial campaign ethics because simply listing the names does not qualify as publicizing “endorsements” and posting their names on an invitation to a campaign fundraiser does not qualify as an “advertisement.” The invite was shared by Kentucky Right to Life Executive Director Addia Wuchner, the Kenton County Republican Party and the 4th Congressional District Republican Party, among others.

Fischer also brands himself as a “conservative Republican.” Bilby, running solely in the less conservative Franklin County, has stuck to “constitutional conservative” in his campaign materials.

The Judicial Ethics Committee opines in a unique way when it comes to advertising one’s partisan affiliation. A judicial candidate can’t use a symbol often associated with a political party, such as a donkey or an elephant, but candidates like Fischer can send out mass advertisements and adopt signage that brands them as a “conservative Republican.”

The Judicial Ethics Committee has run afoul of the courts before, most notably via a First Amendment case brought by another Northern Kentucky conservative judicial candidate Robert Winter and others.

U.S. District Judge Amul R. Thapar struck down parts of the previous ethics code that prohibited publicly declaring membership in a political party; on giving political donations; on engaging in political activity in general; on speaking for or against a political organization or candidate, short of an official endorsement.

An initial opinion in response to Fischer’s question about whether or not a candidate can advise voters of their political affiliation was significantly changed more than three months after its initial publication. After the Herald-Leader reached out to the committee and both candidates about the opinion, a secretary for the committee submitted a corrected opinion to the Herald-Leader last weekend.

The corrected opinion, authored by committee chair and Court of Appeals Judge Irv Maze, noted that “Judicial Candidates have been permitted to announce their political affiliation in mass mailings,” whereas before the opinion did not offer a straightforward response and instead encouraged candidates to not “make hollow” the requirement that judicial elections be nonpartisan.

“It’s a delicate balance,” Former circuit court judge Charles Boteler said, of the commission’s attempt to keep judicial races nonpartisan while also avoiding a successful suit against code such as Winter’s.

Several among Kentucky’s legal community, including Boteler, value the nonpartisan nature of the state’s judicial elections because they say it creates a tighter seal between the judiciary and the state’s other branches of government.

“The most important thing for a judiciary as a separate branch of government is that they’re an independent judiciary,” Corey Shapiro, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky, said. “Once partisanship is sort of layered on top of that, then it no longer becomes independent.”

Fischer simply disagrees.

His brother, Ohio Supreme Court Justice Patrick Fischer, has had it both ways in a neighboring state that recently switched to a fully-partisan supreme court. Joe Fischer said his brother told him he was “much more comfortable” running in a fully partisan manner.

When asked about why he decided to try and make the switch from the legislative to the judicial branch, Fischer first pointed to frustrations that the Republican-led supermajorities in the legislature have run up against, both with the governor – Democrat Andy Beshear – and the nonpartisan judiciary. He stated that Beshear and the courts are a hindrance to policy enacted by the GOP-led legislature, and that the situation needs to be rectified.

“Since Republican policies have been passed by both houses, we’ve had a problem, or we’ve spent a lot of time trying to identify how those policies will be enforced on the executive branch and whether they’ll be upheld by the judicial branch. We’ve met some hostility from both branches of government,” Fischer said. “The seats in the judicial branch only become open every eight years. So if there was going to be some change in direction for the judiciary, then this is the year we needed to step up and try to rectify the situation.”

Keller framed Fischer’s campaign as emblematic of the legislature’s desire to “take over.” She said that Republican state legislators say as much at their events.

“They’ve unabashedly said they want to take over the courts. When one branch wants to take over another branch, that’s halfway to anarchy and that ought to concern every citizen, not just lawyers and judges. We have people in office who think that one branch dominating another is a good thing. They say it out loud. Democracy is a three legged stool, and when any one leg topples we have a problem.”

Fischer was quick to state his belief that he was not the only candidate with partisan leanings. He pointed to Ballotpedia’s labelling of Keller as a “Mild Democrat” based on the fact that she has donated a small amount to Democratic candidates, received a donation from the Democratic-leaning AFL-CIO labor group and was appointed by Steve Beshear.

“One reason I think the law recognizes that candidates should have the right to freely identify their own party affiliation and political philosophy is because if we don’t other parties will fill in the gap. Candidates’ partisan inclinations will be publicized, whether the candidate likes it or not, so my feeling is that each candidate needs to get out in front and make the identification before somebody else does,” Fischer said.

Conversely, at least some Democrats in Northern Kentucky are supporting Keller, who’s an Independent, as if she were a Democrat according to Salzman.

Keller said that she has raised over $100,000 in her effort to remain in her post thus far. Fischer has reported just over one third of her amount to the Kentucky Registry for Election Finance thus far.

The ‘next front line’ on abortion

A headline in the New York Times from earlier this month reads: “Next Front Line in the Abortion Wars: State Supreme Courts.”

Abortion, along with challenges to Democrat-led House redistricting maps, has been a key issue in Fischer’s 20-plus-year legislative career. The Times made note of this in its coverage, and Fischer is not exactly shy about his work in the other branch of government – though he emphasized that he can’t opine on anything that might involve the court that he’s seeking to join, which includes both the trigger ban and the constitutional amendment

“For those who want to discuss it, I tell them my legislative record. By disclosing that, they understand where I stand on that issue,” Fischer said. “I try to limit it to my record.”

Salzman said the race could be the most important one in Kentucky this year in part because of the issue of abortion, but “people aren’t aware” because of the nonpartisan nature of the race.

“If Michelle Keller were to win this race, it would be a huge defeat for Joe Fischer, the Republican Party stalwarts, and the more sort of fundamentalists on that issue (abortion) that are supporting him because they see a real opportunity for a win there,” Salzman said.

Rep. Savannah Maddox, R-Dry Ridge, has joined other Northern Kentucky Republicans like U.S. Rep. Thomas Massie in directing voters to support Fischer. She pointed to abortion – she co-sponsored the bill that got the constitutional amendment on the ballot – as a primary reason for her support.

Maddox is a leading figure in the ‘Liberty’ wing of Kentucky GOP politics, which has been characterized by energetic fights against vaccine mandates, any gun restrictions and occasionally the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce. She’s also running in the Republican primary for governor.

“I support him fully because he has a track record of standing up and speaking for those who can’t speak for themselves… He was kind enough to allow me to sign on as a primary co-sponsor, but make no mistake: that effort was headed up by Joe Fischer,” Maddox said.

Keller was similarly limited in what she could say on the abortion issue, but noted both her catholic roots and her commitment to the Constitution – she included a reference to her previously affirming death penalty cases despite her Catholic beliefs.

“I’m a practicing Catholic and I believe in the sanctity of life, from conception to natural death, because that’s what my church teaches. That’s what I personally believe,” Keller said. “But I took an oath to uphold the Constitution and laws of the Commonwealth.”

Salzman said that the timing of the Kentucky Supreme Court’s ruling on the state’s abortion ban could have an impact on Fischer and Keller’s race. If the court narrowly strikes down the ban, then all of the sudden Fischer could become the anti-abortion movement’s “savior,” Salzman said, to ensure that another ban could pass legal muster.

Regardless, he predicted a lively campaign.

“There’s gonna have to be a ground war for that race,” Salzman said. “They’re gonna have to go knock on doors, they’re gonna have to go do all that stuff, because it is nonpartisan. I’m just gonna have to not get on Facebook for six weeks. It’s just going to be shoved in our faces.”