One of Idaho’s most significant historic buildings is about to get a renovation

A couple of years ago, the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office pulled one of those April Fools jokes by posting on social media that it had to sell the iconic Assay Office building in Boise to make way for condominiums.

Fortunately, that was indeed a prank.

So if you see construction equipment at the building, 210 W. Main St., over the next few months, don’t be alarmed. The historic building dating back to Idaho’s territorial days is not being torn down.

It’s just being renovated.

“We think it’s a pretty special building,” Dan Everhart, Idaho State Historic Preservation Office outreach historian, told me in an interview. “We love living in this building. It’s just ready for a little refresh.”

The Assay Office, built in 1871 and opened in 1872 by the U.S. Treasury Department to process gold and silver in Idaho’s early mining days, is one of Idaho’s most historically and architecturally significant buildings. It’s one of only four buildings in Idaho designated as a National Historic Landmark, which is one step above a listing on the National Register of Historic Places and given only to places that are of national significance.

But at 152 years old, the building needs a little TLC.

Most of the work, expected to begin in the next couple of months, will take place in the basement, which has become damaged from water infiltration. The bulk of the work will be constructing an underground wall 8-10 feet from the building to protect it from further water damage.

Once that’s done, interior walls in the basement will be constructed, asbestos flooring will be removed and new flooring installed, and a kitchenette will be built along with a new conference room and flex office space, all in the basement.

Some work on the first and second floors will be mostly cosmetic.

Not many changes will be noticeable on the outside of the building — except for the color of the front doors. The old U.S. Forest Service green has become faded and not original to the building. The doors will get a new coat of paint, back to the original chocolatey brown color.

What about those bars on the windows?

Perhaps the biggest noticeable change on the outside will be the bars on the first-floor windows. They’ll be removed.

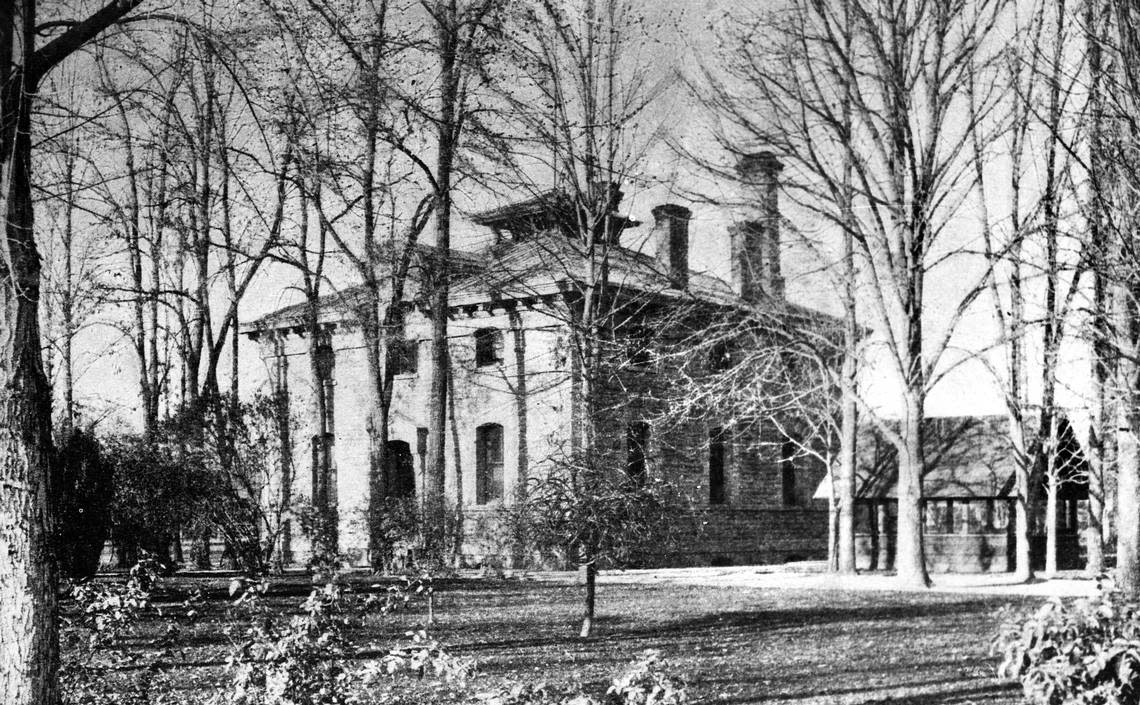

It turns out those bars are not original. Photos from the 1890s show the windows without bars. The bars were added sometime around the turn of the 20th century, which made sense as thousands of dollars of gold and silver were being stored in the building at the time.

In 1932, the building was transferred to the U.S. Forest Service, which removed the bars when it moved in and put in new windows.

In 1972, the U.S. Forest Service turned over the building and land to the Idaho State Historical Society. Unfortunately, the Historical Society reinstalled the bars on the first-floor windows.

So, as part of this latest renovation, the bars will be removed, returning the building to its original look in 1872.

An ongoing renovation project

Work on the building is actually part of an extended project meant to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the site in 2022.

At the time, the State Historic Preservation Office used $350,000 in private donations and a match from the Capital City Development Corp., Boise’s urban renewal agency, on a landscaping project that included rehabilitating the irrigation system, planting 25 new trees (including three new American linden trees to match the old ones) new shrubs, an ADA-accessible track around the perimeter of the property, six new benches and more. Interpretive signs are coming soon, Everhart said.

Everhart said the lush lawn is historically accurate, meant to symbolize the early settlers’ conquering of the harsh desert landscape. So it remains.

The building renovation is expected to cost $1.5 million. A third of the money comes from the federal Save America’s Treasures grant program. A third comes from the Idaho State Permanent Building Fund, and a third comes from the state general fund earmarked for deferred maintenance projects across the state.

Building’s history dates to gold rush

The Assay Office, completed in 1871 and opened in 1872, cost $75,000 to build. It was used as an assay office from 1872 until 1932. An estimated $75 million worth of gold and silver passed through the office. An assay office melts down ore to separate gold and silver from impurities, leaving behind pure gold or silver, which was then weighed and exchanged with miners for cash or bank notes.

It’s a relatively small building by today’s standards, just two stories, plus a basement, designed by architect Alfred B. Mullett in the Italianate style, with a rooftop cupola for ventilation.

But it was by far the largest government building in the territory and a symbol of the federal government’s presence.

“At the time, it was architecturally significant,” Everhart said. “It was a large, imposing structure, the likes of which no one had seen before in Idaho. There was nothing like this building. It was by far the most important in the territory, economically and architecturally.”

It’s made of Boise sandstone, locally quarried, because without train service, it would be nearly impossible to bring in the material to build it.

It’s literally branded. If you look closely up at the top of the building facing Main Street, above the second-floor center window, you can see the U.S. Treasury logo etched in stone.

And above the first floor is a six-petal flower, the ancient symbol for gold.

By 1932, the need for such services was on the decline. Mining became industrial and larger in scale, and mining companies had their own assay offices and means of selling gold and silver, and it was no longer a necessary government function.

At the same time, timber and agriculture was going strong, so in 1932, the Treasury Department turned over the building to the U.S. Forest Service, a division of the Department of Agriculture.

The Forest Service made a number of changes, mostly to the inside of the building, including a widened central staircase, a coal-powered heating system, new windows and a new layout for offices on the first and second floors.

It seems remarkable now, but in 1972, the federal government handed the property to the Idaho State Historical Society.

At the time, when the society administration moved in, there was only one person in the State Historic Preservation Office. Over time, the State Historical Society staff moved into other offices, and the State Historic Preservation Office grew in size. The State Historic Preservation Office today has 12 full-time employees and occupies the Assay Office building.

The State Historical Society has done a little work on the building since 1972, including tying into the city’s geothermal system, but other than that, not much has changed in 52 years.

The only remaining original part of the insides of the 1872 building is a stairway leading to the basement and the basement back door. Those will remain. While the back door was original, State Historical Preservation Office staffers noticed that the door knob was not. The building’s original door knob, complete with the U.S. Treasury logo, was found after a search of the Idaho State History Museum’s collection. From the original, a new door knob will be recast as a replica.

The original investment? $75,000 from Congress

The Assay Office played a significant role in the development of Idaho, particularly in the history of mining in Idaho.

Idaho’s gold rush came a little bit after the gold rushes of California and Oregon, so when gold was discovered in them thar hills around Boise, Idaho saw a reverse migration of miners coming back east from those states to stake their claims here.

By 1862, Idaho had been discovered, with gold in the mountains north of the Boise Valley and silver to the south in the Owyhees, particularly Silver City.

Between 1861 and 1866, Idaho’s gold output totaled somewhere between $42 million and $52 million, or about 19% of the United States’ total during this period, putting Idaho third — after only California and Nevada — in gold production during that period.

Once Idaho was discovered, and the gold and silver started flowing, the federal government saw the need to manage the economic wealth that was coming out of the territory.

Seeing this increased activity, the federal government in 1863 sent troops to Boise to set up a military post to protect the gold and silver that was being discovered. President Abraham Lincoln had just established the Idaho Territory, and a military post was established where the Veterans Affairs Hospital stands today.

In 1869, Congress appropriated $75,000 to establish an assay office in Boise, where miners could bring their gold and silver dust and nuggets and exchange them for cash or government notes.

A gold and silver exchange in Boise

In 1869, the closest assay office was in Denver or San Francisco, and there was no train service to Boise until 1883, which meant any gold and silver collected at the assay office had to be transported overland by stagecoach, likely down to Salt Lake City, where the transcontinental railroad had been completed, and shipped by rail to Philadelphia, where it entered the national reserve and was turned into U.S. gold and silver coins.

Miners would travel from all over the region with their gold and silver dust and nuggets and bring them to the assay office, where the clerk would weigh and process the material. It would be melted down in smelters in the building’s basement, purified and turned into a single ingot of pure gold or silver. That would be weighed again, and the miner would be paid in cash or a government note.

Historians are not sure how often the Boise assay office transported its gold and silver, but Everhart noted that it’s remarkable there aren’t stories of bandits absconding with a haul or two.

The building also served an incredibly important purpose in attracting miners from all over the Boise region, even from eastern Oregon, northern Nevada and North Idaho.

The chief assayer and his family lived in a three-bedroom apartment on the second floor, with offices on the first floor, and smelters in the basement.

The apartment would have been an attraction at the time, as many people in and around Boise were living in tents, prove-up shacks or primitive cabins. To live in a nice, finished stone building would have been seen as a luxury.

The assay office sits on about 0.86 acres on a block that was created when the city of Boise was replatted in 1867.

Alexander Rossi donated the land to the federal government (very un-Idaho of him), and Everhart speculates he did so because he was angling to be named the chief assayer.

It was not to be. Rossi held the job temporarily, until Albert Wolters, a native of Germany, got the job. Wolters, who was chief assayer from 1872 to 1883, oversaw the planting of many trees and shrubs on the site.

The whole block became a de facto park at the time and still is today. Julia Davis Park wouldn’t come along for another 40 years.

Boiseans treated it as their park, donating and planting trees, shrubs and flowers.

Some of the trees on site are at least 120 years old, and you can still see the remains of the double row of American Linden trees that were planted, mimicking the Unter den Linden in Berlin, a famous boulevard that features a double row of Linden trees.

Everhart said settlers of the time came from all over the world and other parts of the country and wanted to create some version of the places where they had lived before. The lush lawn, trees and flowers seemed to be a way of saying they had tamed the desert.

“A federal Treasury facility was extremely important to the development of this area,” Everhart said. “This is absolutely a landmark in Boise.”

Take the survey

The Idaho State Historic Preservation Office is seeking public input to assist in the 2024 update of the Idaho Historic Preservation Plan, which establishes the priorities and goals for the historic preservation community throughout the State of Idaho.

To take the survey, visit https://history.idaho.gov/shpo/

In that effort, the Idaho State Historic Preservation Office is hosting an open house seeking help to prioritize the preservation plan while exploring the recently refurbished and reopened Avery Hotel, including a sneak peek at a couple of the new hotel rooms.

When: 5-6:30 p.m., Thursday, June 6

Where: Tiner’s Alley, 1010 Main St., Boise (the adventurous may enter through the bar’s Tiner Alley entrance, between Main and Idaho streets.

Other Idaho landmarks

Others Idaho structures on the list of National Historic Landmarks are the Sacred Heart Mission in Cataldo; the Experimental Breeder Reactor (the first to convert nuclear energy into electricity); and the “Mole Hole,” a nuclear readiness facility at the Mountain Home Air Force Base, which was designated in December.