One Dodgers rookie stopped swinging because he had to. Data says more MLB hitters should follow suit

PHOENIX — Miguel Vargas, the 23-year-old Los Angeles Dodgers rookie expected to take over at second base, has reached base in one-third of his 15 spring training plate appearances. Good, fine, that .333 on-base percentage would've been solidly above average in the regular season last season. It becomes more (or less?) impressive when you learn that Vargas couldn’t and didn’t swing in his first 11 plate appearances. And everyone knew it.

After he batted .300 or better the past two minor-league campaigns and vaulted from High-A to the majors, the Dodgers aren’t really worried about Vargas’ bat as he steps into an every-day role. The bigger concern is defense because they are asking him to move to second base after he overwhelmingly played third while rising through the system. So when Vargas fractured his pinky finger early in spring, the Dodgers decided he would play to gain experience in the field but refrain from swinging until his finger healed.

In the meantime, Vargas said he played out the otherwise physical decision in his mind. He watched for pitches in specific locations on which he would or would not want to pull the trigger in normal circumstances. Having accumulated just 50 plate appearances in his 2022 cup of coffee with the big-league team, he still has plenty of opponents to learn.

“I’m facing a lot of guys I’m probably going to see in the regular season,” Vargas said. “Kind of starting to face them during spring training is a great opportunity to have an idea of what they do.”

Mentally cataloging breaking balls and pitchers' tendencies, he fired the synapses that determine whether he’d try to lace a line drive to the opposite field or turn on a ball for power, just without firing the muscles.

“That’s what I’m focused on when I go up there,” Vargas said Wednesday, recalling his statue-in-the-box days. “What is my approach against this pitcher?”

When he finally took his first swing Thursday, he connected, drilling a ground-rule double — his first hit and fifth time reaching base. Four times, pitchers walked Vargas despite (presumably) knowing he wasn’t going to swing.

It sounds like a farce. And in many ways, it is, but it joins the adventures of New York Mets pitcher Robert Gsellman — also prohibited from swinging, though less publicly, back in 2016 — in the annals of extreme examples that draw attention to an analytical open secret. One that, if acted upon, would fundamentally change how baseball looks: Hitters might be better off swinging far, far less than they currently do.

Hey, batter batter! Take, batter batter!

The latest study nudging hitters to watch pitches go by comes from Drew Haugen, an analyst at Down on the Farm who set out to quantify swing decisions. Traditionally, plate discipline has been measured in direct comparison to the strike zone. Chase rate tells us that Juan Soto swung at only 19.9% of pitches he saw outsize the zone, pitches that should be balls, the best (lowest) in MLB. Zone-swing rate tells us that Kyle Tucker, the Houston Astros star, attacks pitches that would be strikes an MLB-leading 84% of the time.

Not all would-be strikes, though, are created equal. A lot of them, in fact, are better left alone. With more granular information available about those outcomes, Haugen created swing decision run value (SwRV) to quantify that fundamental decision. While it illuminated a great many interesting things about MLB hitters, it also proved to be another big, blinking sign about how hitters — consistently behind the eight ball in the sport’s recent evolution — might take back some power.

“Using the SwRV data, just 33% of pitches had a higher context-neutral expected run value on a swing compared to a take, while in reality, the league swing rate was far higher at 48%,” Haugen wrote. “Even in-zone pitches should not all be swung at, because a called strike is not as hurtful as a weakly hit batted ball. Only 64% of in-zone pitches have a higher expected run value on a swing than on a take (again, context-neutral).

"Even on swings in-zone, hitting a productive batted ball is very unlikely," Haugen told Yahoo Sports.

His analysis showed that swings on those in-zone pitches "resulted in whiffs 17.8% of the time, foul balls 40.1% of the time, field outs 28.3% of the time and base hits just 13.8% of the time."

When you start to think that through, it makes more and more sense. They might be pitcher’s pitches, too difficult to really do damage against, even though they’re in the zone. They might be exceedingly likely to cause a pop-up (an automatic out) or a weak grounder (something close to that).

Context-neutral is a key bit here. Obviously, a walk doesn't mean as much with a man on second and two outs in a tie game. And not swinging at a strike on 2-2 isn't a good option. In the grand scheme of baseball strategy, however, the lessons in these numbers do apply, and they are not new lessons.

Just last year, Eno Sarris took a deep dive into the matter, and Driveline Baseball’s Kyle Boddy expressed the sentiment more bluntly: “Hitters should not swing.”

Obviously, he didn’t mean totally. If a hitter actually committed himself to stillness, it would be noticed, and it would be exploited. Kansas City Royals starter Zack Greinke, the wily future Hall of Famer, came closest to dropping the charade against Vargas by pumping in fastballs down the middle well below his typical velocity.

In the past decade, only one qualified hitter has registered a swing rate at or below 33%, Matt Carpenter in 2014. He managed to run a .375 on-base percentage despite minimal power. Only 11 other seasons have come in under 36%, with Juan Soto and Joe Mauer doing so twice each. Applying this on a broader scale, though, would require hitters with less discerning eyes and less inherent intimidation to set their bats on their shoulders intentionally.

What would happen next is difficult to say. Haugen brought up Soto and Myles Straw, the light-hitting Cleveland Guardians center fielder, as case studies that show how difficult it is to paint with a broad brush. Both are extremely patient, but pitchers understandably treat them differently. They avoid the zone against Soto, even though he's likely to take the balls and reach base because he is so dangerous when he swings. Straw, on the other hand, saw more pitches in the zone than any other hitter in baseball in 2022.

"But if as a whole, the league decreased their swing rate by about 3-4%," Haugen said, "hitter production would increase," even if pitchers didn't start throwing a much larger share of their pitches in the strike zone.

The question is what that production would look like.

Zack Greinke vs Miguel Vargas AB (pitches ranging from 59mph to 92mph). Greinke f'ing with Vargas who hasn't been cleared to swing. 😂 pic.twitter.com/PwPPPMC5lz

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) March 5, 2023

Optimizing for wins vs. entertainment

While Vargas’ walks were entertaining as a novelty, a game with significantly fewer swings could get very boring very quickly. Maybe Soto, with his trademark shuffle, would keep viewers entertained without swinging. But in most cases, that wouldn't hold true.

Anyone who watches a game in 2023 will reckon with that underlying push-pull of best practices vs. best TV product. MLB’s new rules — mostly the pitch timer and infield shift limitations — are reactions to mass changes in the game that were smart for each team but, in aggregate, downgrades for the sport.

As Sarris pointed out, recalibrating a hypothetical migration away from swinging would be considerably more difficult. Putting baseball on a clock was one thing; deciding that it’s no longer “one, two, three strikes, you’re out” would likely be a bridge too far. Luckily, that remains very much in the realm of the hypothetical, despite the many studies that suggest it might produce better results for hitters.

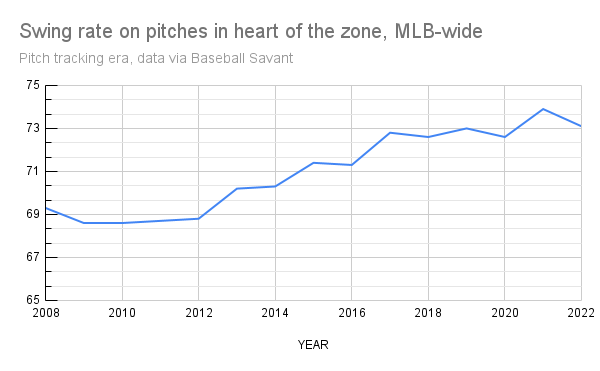

MLB batters in 2022 actually swung more often than they had in the previous 20 years. The last time hitters swung more often at pitches in the zone was 2002, the first year FanGraphs has data on swings. Digging deeper into those tendencies, the logic at work becomes pretty clear. Facing more and more diabolical offerings from pitchers’ ever-advancing arsenals, hitters have simply determined that they need more swings to actually hit one.

Using Baseball Savant’s more granular classification of the “heart” of the zone — pitches down the middle — we can see that these no-doubt, center-cut pitches are drawing more swings than they have since pitch tracking began in 2008.

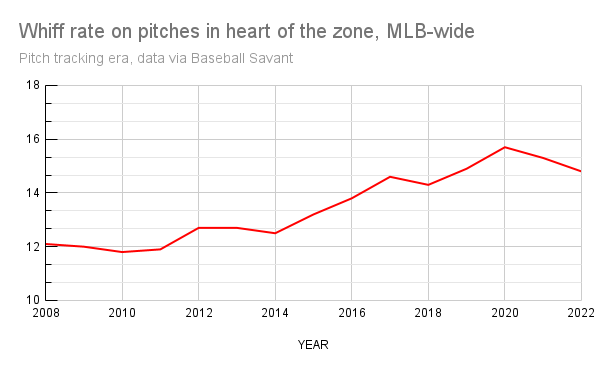

They are also, however, creating more whiffs, despite their seemingly hittable location.

That’s the amped up movement of modern pitch design at work. Yes, maybe a hitter would be better off taking a high fastball because a deeper count might force the pitcher to throw one lower or simply provide another opportunity for him to make a mistake. But if you’re standing in the box facing, say, Spencer Strider, how confident are you that you’ll put good wood on that one? How confident are you he will even offer another fastball?

That psychological dance is still winning out over the theoretically optimal passive-aggression. Maybe it always will. But as Vargas learned this month, the same nasty stuff that keeps hitters busy in the box also keeps pitchers operation on the razor’s edge between in control and out of control.

”Baseball is hard,” Vargas said. “For hitters and for the pitchers, too.”