The One Beautiful Word the World Almost Ruined

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In my house we use the term life hack with casual irony. Turn off the light when you leave a room, my boyfriend will tell my teenage son. Life hack! Or, brush your teeth, man! It’s a life hack! Or, there’s a life hack we learned the hard way: Don’t let the puppy pee on the couch.

But awe is a real life hack.

It’s a trendy word these days, awe—like wonder and bliss. It has been overused to the point of ruin. Yet behind the hype there’s a genuine secret: The capacity for awe is a means of survival. People who can feel awe, studies show, have more resilience in the face of loss than those who don’t. If you’re able to be captured by a sense of wonder when you look at landscapes or art, it turns out, you have a greater chance of recovering from failed relationships or chronic loneliness.

While those studies are useful, I don’t need them to tell me how life changing awe can be. And neither does anyone else who’s known the presence of the sublime, whether through worship or gazing at ocean waves rolling in or suddenly glimpsing an ethereal realm of clouds through an airplane window. The findings match up with our simple, direct experience: that you can be rescued from your daily troubles by a fleeting second of transcendence. How you come to it hardly matters. What matters is the sensation of being swept up, part of an eternal lineage—a trace in magnificent vastness.

Each fleeting second seems like a form of grace. I had a few encounters with them as a young person. I recall once, on a high balcony at night by myself, looking up at stars and marveling at the universe’s infinite expanse. But, casting further back in memory, the first time I felt their uplift wasn’t in an epic countryside or on some voyage of discovery. And I wasn’t alone but surrounded by strangers. It was the gift of a little cassette-tape player and a pair of black-foam earphones.

I used to ride a bus and a subway train to my high school, and the trip was at least 45 minutes each way—this started when I was 12 and lasted for six years. It was in the ’80s, before the advent of cellphones. I liked to read library books while on public transit, but soon there was another element to my commute. Walkmans had been invented, and I was able to save up and buy one for myself.

I remember one winter morning setting off from my home to the bus stop, bundled up against the biting cold, with my new cassette player in a coat pocket. I switched it on and heard a soaring music. Graying slush at the edge of snowdrifts faded, along with a long stretch of cemetery I had to walk past, where piles of trash, cigarette butts, and dirty ice were shored up against the forlorn gravestones. So did the facade of a grim, dilapidated apartment building that looked like a prison and always made me feel sad.

But on that walk or bus and train rides, I had the company of songs.

Though my route was the same every day, the music didn’t have to be. I could choose my sounds. The music was from anywhere and made by anyone, from anytime since the dawn of recording and even before. Like books, the music might have been made by a person who had already finished living. And could speak to me anyway. In private and from the heart.

If I was feeling down, the songs might be upbeat. If I was feeling anxious, maybe they were calming. Most of us know it now, the consolation and inspiration of listening to personally curated music in public spaces, but it was new then. It brought me the euphoria of listening to voices of people I’d never know. Loneliness was dispelled, apathy was transmuted into energy, and the flatness of self-absorption turned into a giddy communion with feelings and perceptions of others, made rapturous by poetry and sound.

I only realized later how crucial that listening had been. It transported me out of myself and into the greater world.

I still go to music for elevation and catharsis, though my Walkman has been gone for many years, along with the iPod that followed it. And I go to nature, as well—wide skies of the desert where I live or high mountains I can drive to, where a pine forest spreads out around me and tall, old trees breathe out oxygen, swaying softly in the wind.

You can’t design a moment of awe. That’s part of what makes it possible. Sometimes music is just a background and landscape is only pleasant scenery.

And that normalcy, too, is a necessary condition.

But now and then, in an instant, they can turn into a revelation. Grandness and loveliness and majesty.

“There is a crack, a crack, in everything,” sings Leonard Cohen. He’s gone now, but his voice is as beautiful as always. “That’s how the light gets in.”

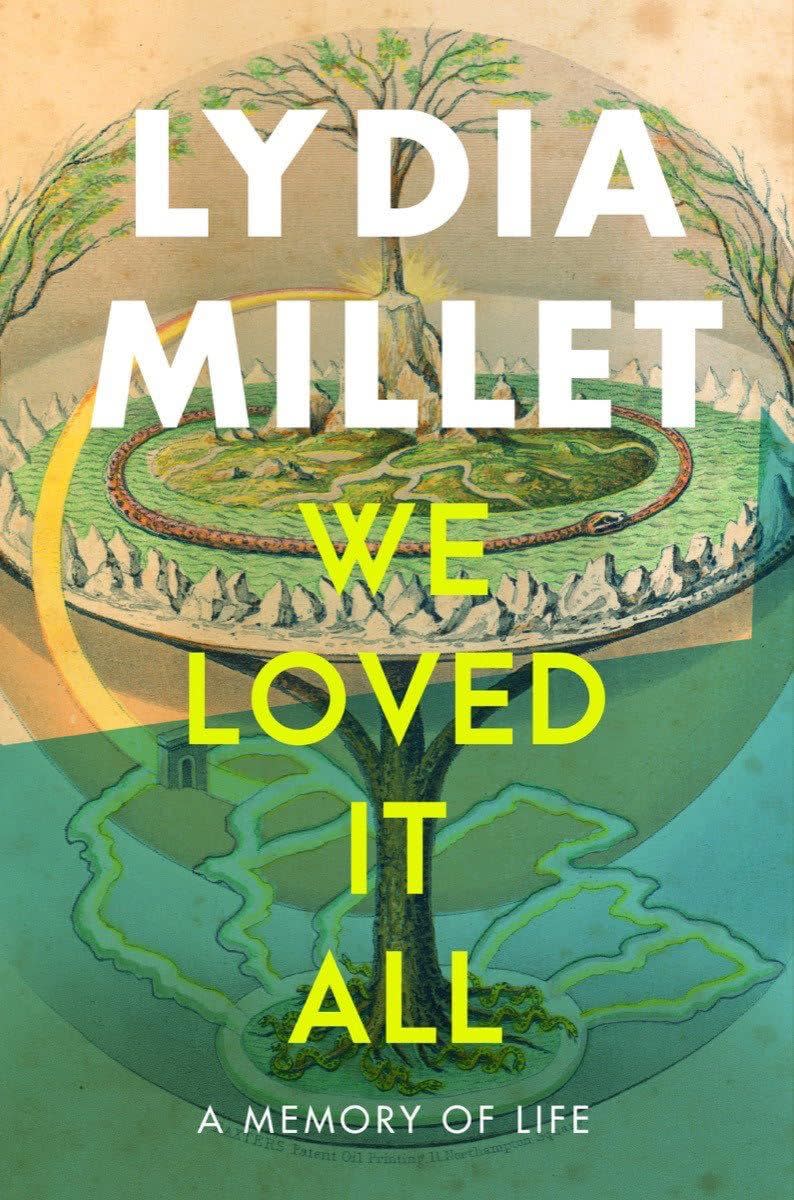

We Loved It All, by Lydia Millet

amazon.com

$25.19

Lydia Millet has written more than a dozen novels and short-story collections, including We Loved It All (2024) and A Children’s Bible, which was a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction and one of The New York Times Book Review’s Best 10 Books of 2020.

You Might Also Like