Older Wisconsinites have the highest suicide rate of any age group. Why don't we talk about it?

In the year after he was discharged from the Vietnam War, Darryl Johnson couldn't understand why he was having nightmares.

He'd be with his men on long-range reconnaissance patrols along the Cambodian border and one would suddenly go missing. He'd be responding to a fire deep in the jungle only to find himself invisible and helpless. He'd be naked and weaponless as a fire ripped through his base.

It's not like Johnson never had a nightmare before, but the frequency and physicality of his post-war night terrors concerned him — and wife. Night after night, he'd startle them both awake, sometimes bolting out of bed.

What these nightmares indicated for Johnson didn't yet have a name, or at least, not an accurate one.

"The term used then was 'shell-shock,' and I heard that word and thought, Nah, not me," Johnson said.

Plus, a therapist? In the 60s, early 70s?

"That means you're nuts!" Johnson said.

It would take decades for Johnson to understand that his nightmares were a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder. And longer still for Johnson to finally seek help.

At 79, therapy is now a regular part of Johnson's life. But many older adults struggle with an array of barriers that prevent them from seeking mental health treatment, such as stigma, ageism, a lack of providers, and the idea that it isn't a priority at the doctor's office.

That's particularly worrisome because older adults are suffering at a staggering level. They account for a whopping 21% of all suicide deaths in the United States, which is larger than any other age group, according to 2022 preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That's in line with Wisconsin's numbers, too. According to state data from the CDC, older Wisconsinites made up 18%, or 161, of all suicide deaths in 2021. And like the national rates, suicide deaths in older Wisconsinites have jumped nearly 10% since 2016.

[infogram id="f896d28b-1f9d-44e9-8dc0-acf1d98b870d" prefix="dgY" format="interactive" title="Wisconsin's older suicide population"]

There's a disconnect in how we respond to older people struggling with their mental health, said Dr. Sarah Endicott, a clinical professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison focused on geriatrics. Some of that, she suspects, may be chalked up to ageism, which the World Health Organization defines as the stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination toward others based on age.

"I don't think it's intentional, but the lower value we place on older adults in general, especially when it comes to end-of-life, I'm guessing that's part of the cause," said Endicott, who also works as a geriatric psychiatrist at Stoughton Hospital in Dane County.

But another reason we don't talk about it has to do with where mental health falls in our priorities as we age, according to Endicott. With all the cascading medical conditions that can come with age, depression tends to plummet down on the list when discussing health problems with a primary care physician.

Prioritizing mental health in older adults is a struggle for physicians, too, because they only have so much time to spend with individual patients.

"You have somebody coming in who has congestive heart failure and diabetes and arthritis and maybe cancer. They're also depressed and you have 20 minutes to spend with them," Endicott said. "Well, in that 20 minutes, you're going to focus on the diabetes and the congestive heart failure."

Plus, since many older patients have been conditioned to bottle up their feelings, getting them to talk to a medical professional takes time — which a doctor's visit hardly affords.

That's even more apparent when we consider causes of death in any given age group. Even though more older adults die by suicide than most other age groups in Wisconsin, it's not one of the biggest perceived threats, according to the CDC. Not when the greatest health risks to Wisconsinites over 65 come from heart disease, malignant tumors, COVID-19, Alzheimer's and stroke, the top five causes of death in 2021.

Suicide is a problem in any age group, but we're more inclined to talk about when it happens to younger people. That's because younger people, generally, aren't at risk of fatal health problems. Even though not more than 22 Wisconsin children aged 10 to 14 died by suicide in 2021, it's the second leading cause of death for that age group. Essentially, we notice death more in this age group because it's rarer.

But shouldn't we still notice and take action when it happens to older adults?

"Absolutely," said Dr. Kenneth Robbins. Robbins is a clinical psychiatrist at Agrace Hospice in Madison and works in the dementia wing of the clinic. He said poor mental health in older adults can cause "a lot of problems," especially for people diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer's.

"I would say 80% of people with dementia at some point have a mental health problem," said Robbins, who noted that it's not uncommon for people to grow suicidal upon receiving a dementia diagnosis. "Obviously, it's not a diagnosis any of us would choose, but if the mental health problems (and) emotional pain are managed, people can do very well with dementia."

Transitions, grief and physical pain exacerbate mental health problems in older adults

Judy Feld, a licensed clinical social worker at Prevea Health in Green Bay, knew her mother would suffer a deep emotional rift during the pandemic. A resident at an assisted living facility, Feld's mother went more than a year without seeing her loved ones in person.

"That was really hard for her," Feld said.

With any population, isolation can increase the likelihood of depression and anxiety, but it's far more pronounced with older adults, Feld said. Often, isolation happens as they part from lifelong careers, lose friends and family to death, and no longer have the physical agility they once did.

The loneliness is acute and specific, especially in the wake of losing a long-term partner. It creates a change in roles, a foundering purpose and anxiety about the future, Feld said. Questions pulse amid the enormous grief like: What's going to happen to me now that my spouse can't take care of me? and: Am I going to have to move to a nursing home?

Suzanne Morley, health promotion program coordinator at Wisconsin Institute for Healthy Aging, said some of the data she's found shows that 43% of older adults feel lonely on a regular basis. They may cross unceremonious milestones that fewer people in their lives can relate to, such as increasing chronic health issues, navigating retirement or not having the means to retire, and no longer being able to drive, Morley said.

And, zooming in to the Badger State brings its own barrel of woes. Many Wisconsin adults take pride in drinking, but they also take their pain to the bottle. Wisconsin exceeds the national binge drinking rate in every age group, including those 65 and older. At the national scale, 5% of older adults 65 and older binge drink, but 8% of Wisconsin's older population binge drink, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Morley said this type of drinking could be an indication of a mental health condition or serve as a coping mechanism for the unique experiences associated with aging.

Farmers are especially vulnerable to drinking, especially as they find themselves aging out of their professions, Endicott said, who works with a lot of older, rural patients. She's found that when rural patients lose the ability to drive, it has a tremendous impact on their access to social connections. They can't exactly order an Uber if they live in the hinterlands, Endicott said. And where would they even go?

Add access to a firearm, which farmers typically have, as well as dangerous equipment, and the risk of suicide becomes "really, really high," Endicott said.

"People who live on farms often have guns, and older adult men who can't participate in farming anymore — that's a really, really difficult life transition," Endicott said. "So there's all these losses, and you think even one of those things might be devastating, but then you compound all these losses … that can really cause a crisis in someone's life."

From quiet and undiagnosed to bursting with expression

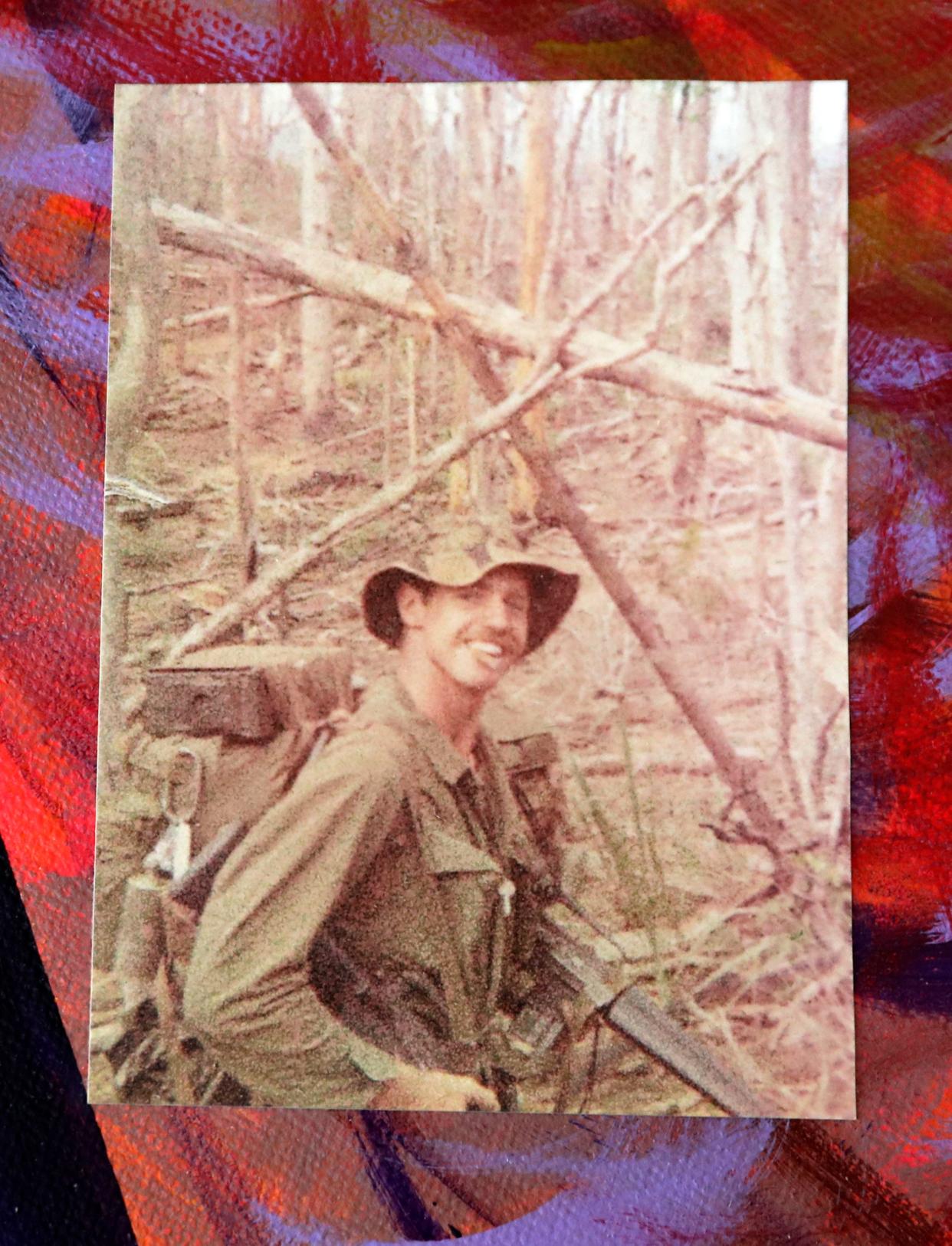

Johnson returned from Vietnam War to a country very different from when he left. He read about the race riots and campus protests, learned he shouldn't come home wearing his uniform if he didn't want to get spit on or screamed at.

"It was an era of unwelcome landings," Johnson said.

Johnson thought it best to not talk about the war. The nightmares raged on for a year. As they dissipated, other out-of-character behaviors started emerging: hypersensitivities, hypervigilance, not responding to emotional events. His family sometimes saw a different Darryl, one who sealed himself off, got quiet for long stretches of time and would bail from social obligations — often, funerals — at the last minute.

Still, the turning point for Johnson happened decades after his discharge when he worked as a social studies teacher at a private school in Green Bay. About a quarter of his middle school students were Hmong American and, during parent-teacher conferences, Johnson often faced a language barrier with his student's parents.

But they found a common language on his classroom map. Those parents had been children of Hmong soldiers fighting in Vietnam's secret war in support of U.S. forces in Laos, across the border from where Johnson was stationed. The parents would point to the villages they grew up in, and they could trace their fingers along the Mekong River, the body of water they had to cross to make their way to the refugee camps in Thailand

The connection allowed Johnson to remember the past anew, but not without guilt.

"I was able to go home after my two years of service and selectively remember those things that were good. Whereas, they lost everything and had to start again with nothing," Johnson said. "It was disturbing."

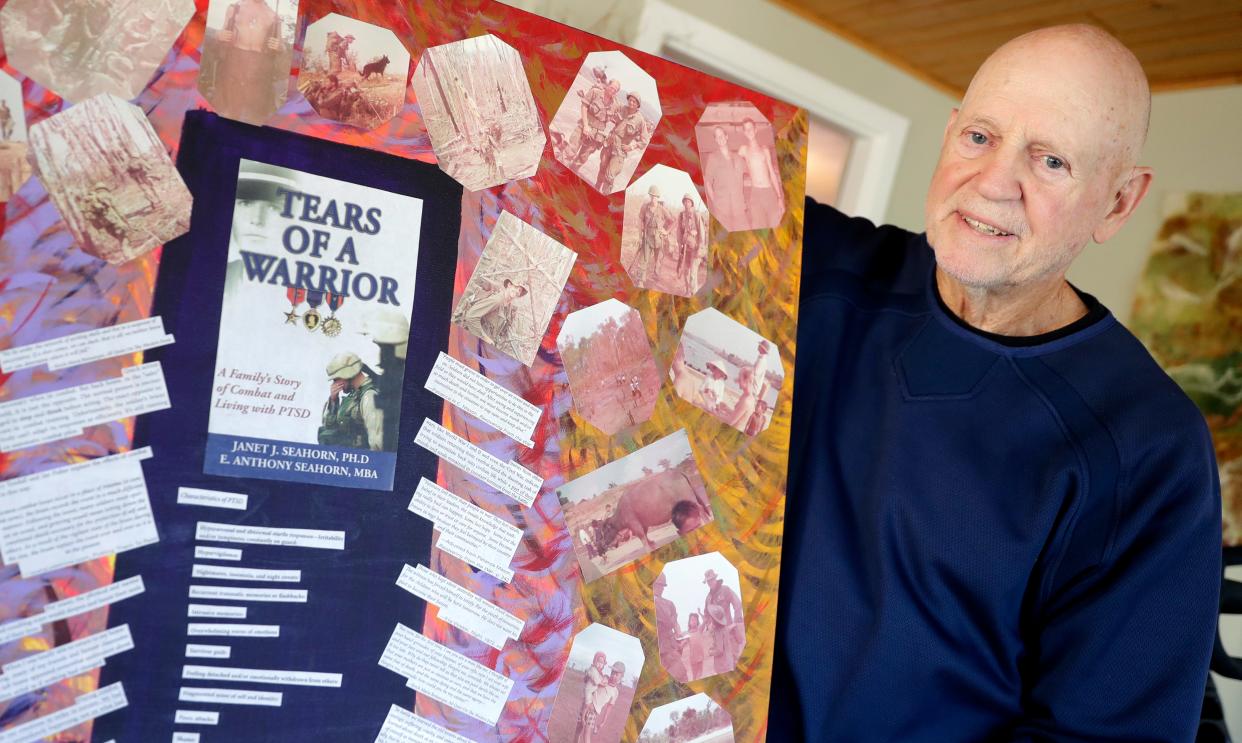

That's when Johnson understood he still carried wounds from the war. With the gentle prodding of his wife, he decided, four decades later, it was time to get treatment for what he was beginning to suspect was PTSD. He looked into his VA benefits and, much to his chagrin, learned he didn't qualify. At the time, the VA didn't cover benefits unless a soldier was physically wounded.

Years later, the VA rules changed on this and, in 2005, he pursued therapy with his VA benefits. He learned from other Vietnam veterans of a therapist trained to work with his population, so he took a chance.

"It's been a great experience, being able to talk to someone about these things. If I wanted to give him some bulls--t reasoning for why I got mad or upset, he'd challenge me," Johnson said.

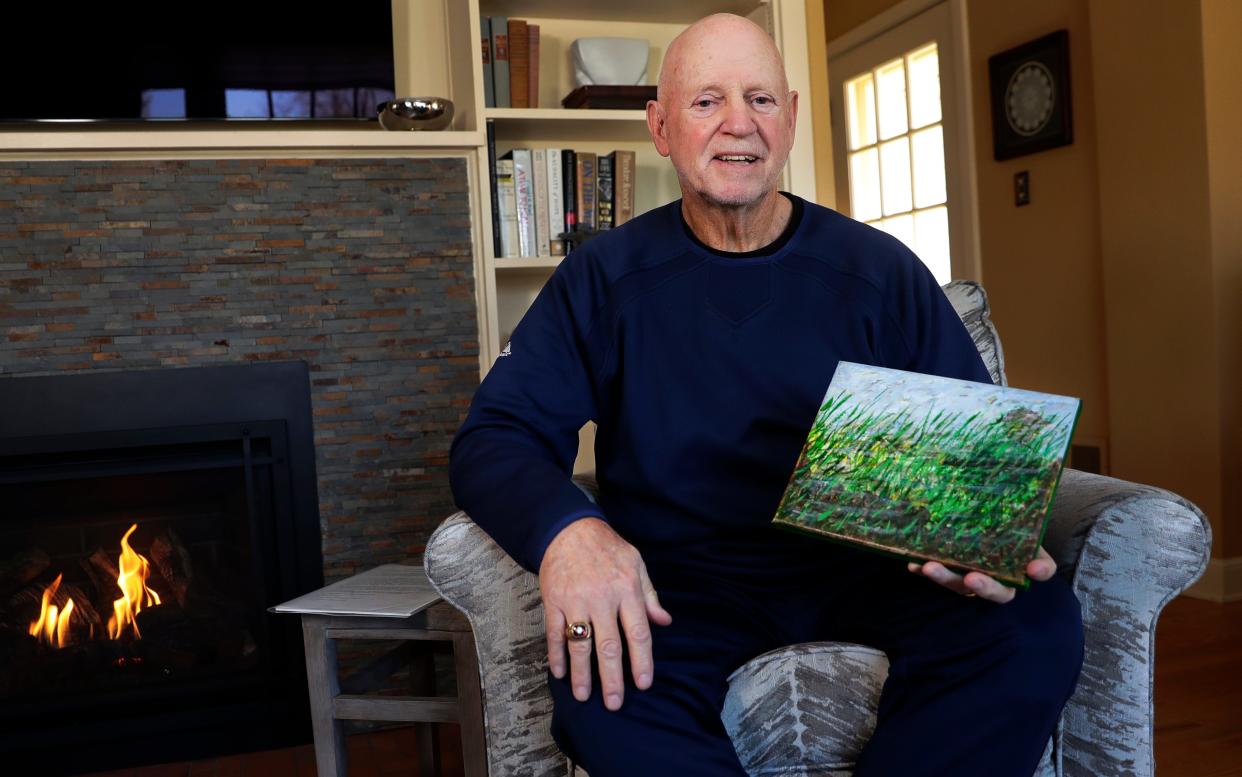

His therapist recommended art therapy to him, an idea that made him nearly laugh out loud. Him? An artist? He couldn't even draw stick figures! But, it turned out, Johnson had a lot to express, mostly about life's contradictions. Love and hate, war and peace, apathy and action. These polarizing ideas became the stuff of inspiration. Plus, swirling colors along a canvas was surprisingly meditative.

Years later, he'd end up displaying work in the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in Madison.

"One of the biggest things for people struggling with mental health is trying something new," Johnson said. "It's so simple: Try something new. It's three words, but it's huge in our lives."

Connecting with other people, despite differences, is key

If Johnson's experience is any indication, humans can hold on to their mental health conditions for the better part of their lives without seeking help. The numbers also shake out this way. According to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, older adults are at least 40% less likely to seek out or receive mental health services than younger individuals.

In Wisconsin, less than 7% of older adults took advantage of crisis services in 2021, according to DHS' Mental Health County Services dashboard. By comparison, nearly 20% of people in this age group sought crisis services.

Endicott, from UW-Madison, isn't surprised by this. Young people are far more attuned to the signs and symptoms of depression. Older adults tend to avoid mental health terms.

"They don't use that term, either because of stigma or they don't recognize it. They don't say things like 'I'm in a low mood' or 'I'm depressed.' It might come out more as irritability, lack of energy, not getting engaged in things," Endicott said.

But it's also the case that very few geriatric psychiatrists exist to help older adults understand this language, Endicott and Robbins both said. There's not a ton of incentive to enter the field, Robbins said. You have to be comfortable with medicine, psychiatry and neurology, Robbins said, especially with regard to the prescription side of psychiatry. In addition, geriatrics is not a very lucrative job because "it's pretty much a Medicare-focused practice," Robbins said.

As it stands, there's already a shortage of physicians in psychiatry. Around 3% of all physicians in psychiatry specialize in geriatrics, Endicott said. Put another way, for all the geriatric psychiatrists in the state, each of them would have to have 20,000 patients, Endicott said. That leaves the majority of behavioral health diagnoses up to primary care physicians, who are already doing more for less.

"Primary care providers are perfectly capable of diagnosing and treating mental health disorders, but they're also the most burdened by lack of time and having to deal with all these diagnoses," Endicott said.

The good news, said Robbins, is that a majority of older adults are quite content with where they are in life. They don't have the same worries for the future that people in their 20s, 30s and 40s have. They're more able to live in the present because, per Robbins, "they recognize they're not going to live another 40 years."

"God knows, people have a lot of issues with mental health as they get older, but not everyone," Robbins said. "And it's important to have a perspective that there are many people who actually feel better as they get older."

Today, Johnson makes things at his house in Allouez. He keeps himself busy through pursuit of creative practice. He likes to make birdhouses, which he gives away to his friends and neighbors.

Johnson doesn't have all the answers, but he's learned the importance of connection, a struggle that so many older adults face. For him, forming positive relationships with a diverse set of people has helped him gain new perspectives and try new things, whether it's the Hmong parents whom he'd continue knowing and learning from for years, or the people he meets in art therapy.

"I always tell people: You are who you hang with. In today's world, we can be a whole lot more healthier if we have friendships that are diverse, who can help us try something new," Johnson said. "I'd say get yourself in alongside other people who maybe you don't know, people who've experienced trauma. To me, it's been the best thing."

Where and how to get help

Endicott said family can be an extremely important resource for older adults. Her advice, and this isn't exclusive to older adults, is to always check in and be direct if you notice a family member withdrawing. It's especially vital for older adults, who may not volunteer when they're having a mental health struggle, Endicott said.

"It's about more people being proactive, being direct, showing up more, not being afraid to say, 'I'm worried about you,' and being a good listener," Endicott said. "You don't have to be a mental health professional to really help people just by listening well."

In addition to family support, here are a few resources experts from this story recommend for older adults who are struggling with their mental health:

Find your local Aging and Disability Resource Center. The ADRC has information about a variety of services and programs, including wellness programs and long-term counseling. (www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/adrc/consumer/index.htm)

Wisconsin Institute for Healthy Aging. WIHA runs several evidence-based programs and practices available in English and Spanish. (www.wihealthyaging.org)

Wisconsin Coalition for Social Connection. WCSC helps connect older adults for social activities ranging from volunteer, taking a health promotion class and offering tips and tricks to getting out there. (www.connectwi.org)

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Wisconsin. NAMI Wisconsin offers peer-support groups to anybody struggling with mental illness or a loved one's mental illness. Find your local chapter. (www.namiwisconsin.org)

The Institute of Aging has a Friendship Line, available to anybody who feels alone, isolated or depressed "because sometimes we all need a friend." It also has a service for elder suicide prevention and grief support. The toll-free number is 888-670-1360

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Older adults are hurting. Why do we sidestep their mental health?